Picasso

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon | Pottery and Ceramics

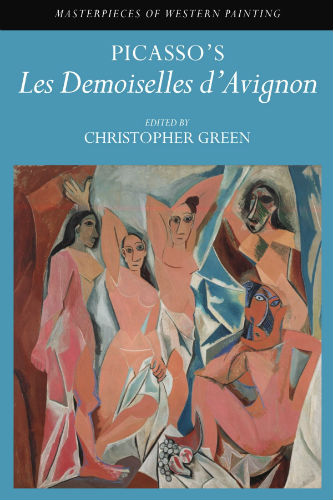

PICASSO: LES DEMOISELLES D’AVIGNON

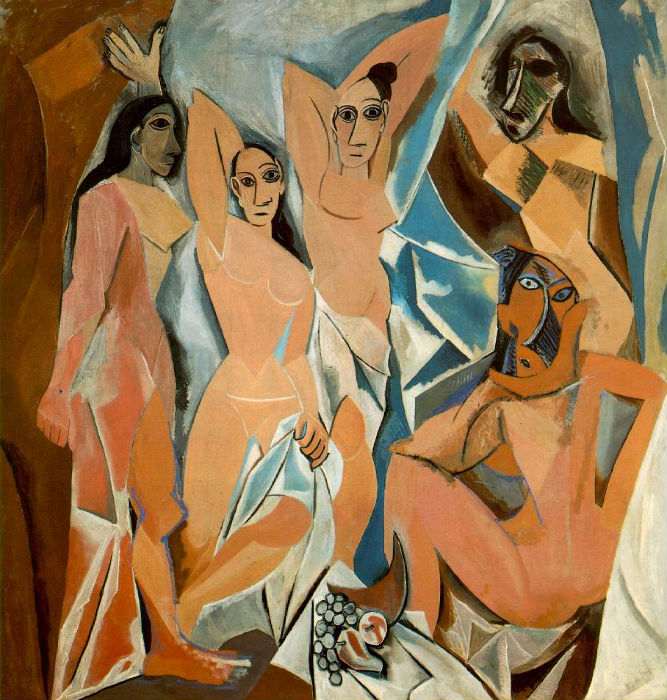

Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907

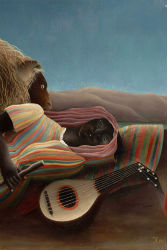

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Five Chapter 8

When you surprised yourself in the mirror, when you became a stranger to yourself, who was the who you dreamt yourself to be?

̶ Mirror, mirror, tell no lies, how do I look in Picasso’s eyes?

Aghast, you stand before me as my vibrating vision seeks a place of rest; in the wild confusion of coordinates, all I find is sex. Look! Within the constriction of the picture frame, you’re exploded into five viragos, five Amazons of the archaic impulse, five avatars of eros. Through your orgiastic iciness your black eyes pierce, giving me no escape from engulfment. Look! Ground and figure reverse, voids solidify; contiguity begets distance, depth surfaces: Everything about you testifies to the excess of sex.

CHRISTOPHER GREEN: INTRODUCTION TO ‘LES DEMOISELLES D’AVIGNON’

From ‘Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’, ed. Christopher Green (Cambridge UP, 2001)

All images (except ‘Gertrude Stein’) are screenshots from Picasso érotique, Editions Montparnasse DVD, 2007.

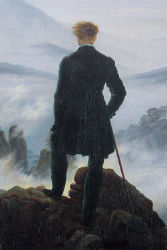

As an artist, Pablo Picasso was well prepared for fame. There was always a spotlight on him. His stage might have been small and without glamour to begin with, but he was always aware that he had an audience. Even in the late 1890s, as an apprentice modernist in Barcelona, he was recognised to be a prodigious talent. He first showed in Paris at the age of nineteen, when he was selected for the official exhibition of Spanish art at the Universal Exhibition of 1900. Within a year, two of the new galleries showing young ‘independent’ painting in Paris, Berthe Weill’s and Ambroise Vollard’s, were buying from him. In May 1901 Vollard gave Picasso a show all to himself, a rare accolade.

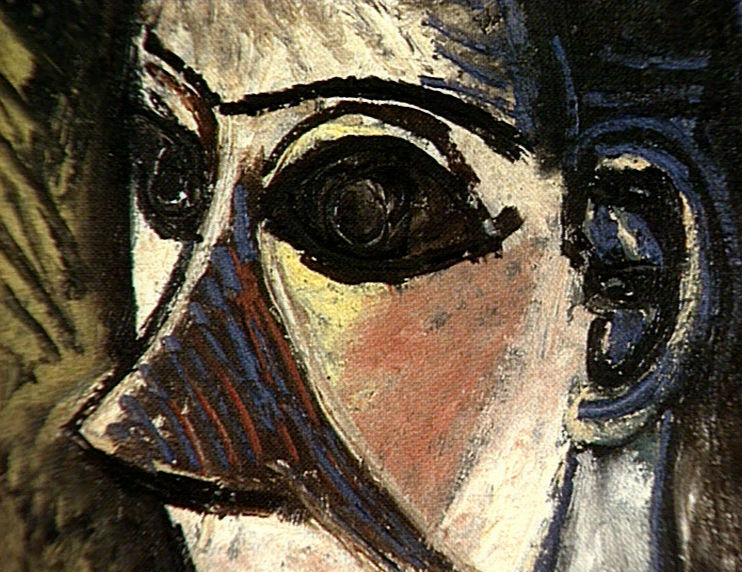

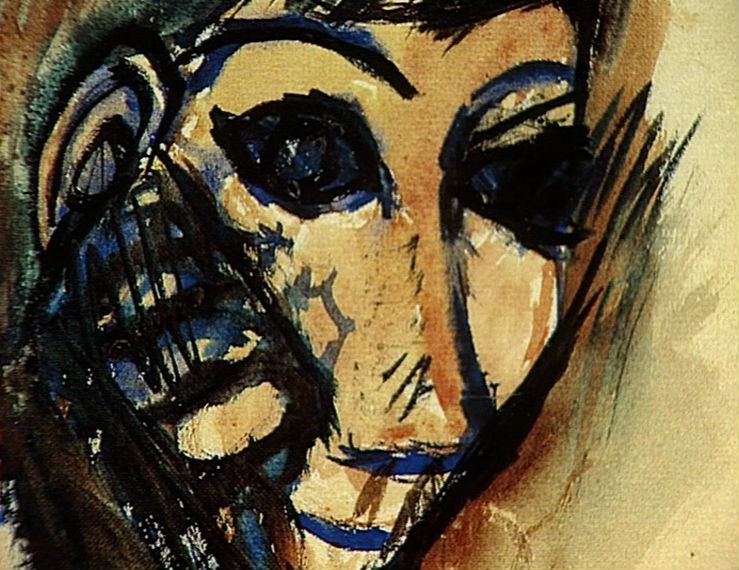

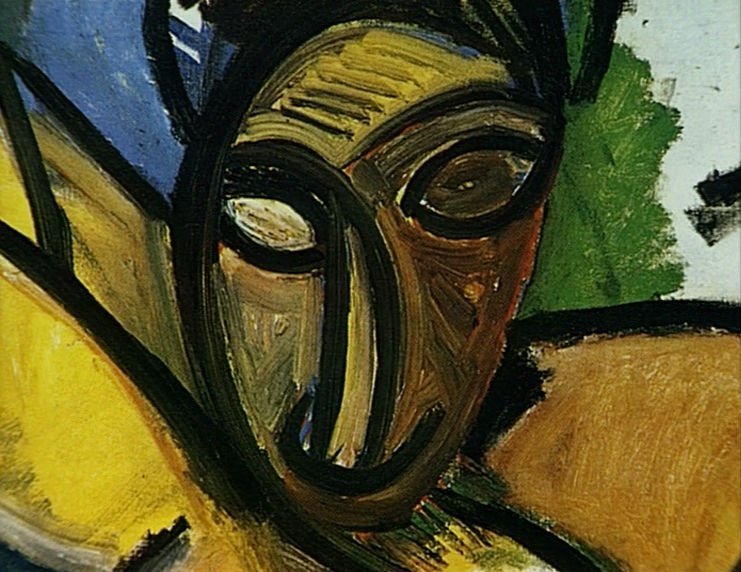

Picasso, Study for Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907

Picasso, Gertrude Stein, 1906

Between 1901 and 1904, he kept aloof from commercial success, painting underclass poverty from the vantage point of bohemian poverty mostly in Spain, but after he settled finally in Paris in April 1904, a circle of collectors and dealers keen to buy from him formed quickly enough. By 1906, among them was the American writer Gertrude Stein, whose portrait he completed that autumn. Her support and that of her brothers and sister-in-law (Leo, Michael, and Sarah) gave him a position comparable to that of the older Henri Matisse, acknowledged leader of the ‘Fauves’, for they had been among the first buyers of Matisse’s ‘Fauve’ work in 1905. Though still only in his mid-twenties, it was, therefore, as an emerging modernist leader—at least for a select few—that Picasso started work early in 1907 on the huge, almost square painting that would become known as Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

By 1914, Picasso, the acknowledged inventor of another major -ism, ‘cubism’, was as famous a modernist leader as Matisse. It took a further twenty-five years for the Demoiselles to begin to emerge as one of the most important paintings not only in his oeuvre but in the early history of modernism altogether. And yet, even while he was at work on the canvas, before the summer of 1907, talk of it had reached not only Vollard, but the young German dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, newly launched in Paris, who would become Picasso’s dealer, and Félix Fénéon, manager of the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, who would become Matisse’s. It may not have been exhibited at that time, but many came to see it in Picasso’s Montmartre studio, artists and writers besides dealers and collectors, friends like the poet André Salmon and the painters André Derain and Georges Braque, visitors like the English painter Augustus John. As Picasso himself had, the Demoiselles made an impact before it became famous, and, for its small but influential audience, that impact was so great because it was so dramatically different from anything Picasso himself or any other artist working in Paris had so far painted.

Picasso, Study for Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907

Picasso, Study for Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907

There was much about the Demoiselles that was not different. Picasso had painted prostitutes before, and brothel subjects were a late-nineteenth-century genre. He had also taken on the theme of sexuality and danger before. His major painting of 1903, Life, uses allegory to do the job. And he had used expressive colour and formal distortion before too. What differentiated this picture was the way its distortions challenged the most basic assumptions about the pictorial depiction of figures and of space, and the sheer immediacy of its confrontation with so brazen a subject. The force of those differences was enhanced by the openness with which it alluded to painting from the European past: to post-Renaissance figure painting from Titian and El Greco to Ingres. It was enhanced too by the equal openness with which the picture alluded to a non-European present, what then were called the ‘primitive’ cultures of Africa and Oceania. The Demoiselles simultaneously invoked and demolished the canon celebrated in the great museums where Picasso had trained his eye, the Prado in Madrid and the Louvre in Paris.

In the mythology of modernist and postmodern art history, the status of Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon as a painting that marks a dramatic break from the past and a new twentieth century beginning is now unquestioned. Its immediacy, the directness with which the stares of each individual prostitute invite the spectator in, underlines its role in one of the central developments of art in the twentieth century: the empowering of the spectator. We, the work’s spectators, are made the centre of attention. The work becomes not so much Picasso’s statement as a challenge to us to respond and, by responding, to give it meaning. In modernism altogether, art (not merely visual art alone) has been reoriented, placing the onus on the relationship not between the artist and the work of art, but rather between the work and the spectator. Despite this crucial shift, and the role of the Demoiselles in marking it, writing about the picture has been as much devoted to constructing a narrative of its conception and to exploring its relationship with Picasso’s biography, as to the analysis of the kind of experience it offers. Picasso and the way he produced the painting can still be made to seem more central than we–the spectator–and the way we might experience it.

Picasso, Study for Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907

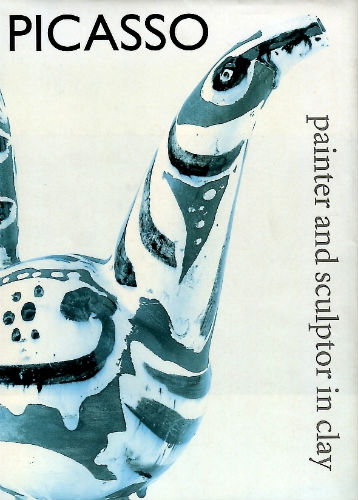

PICASSO: POTTERY AND CERAMICS

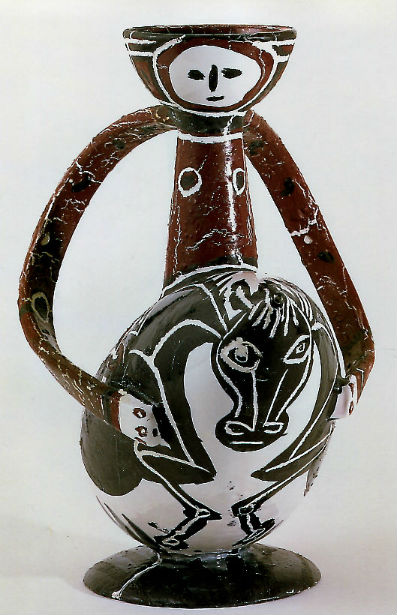

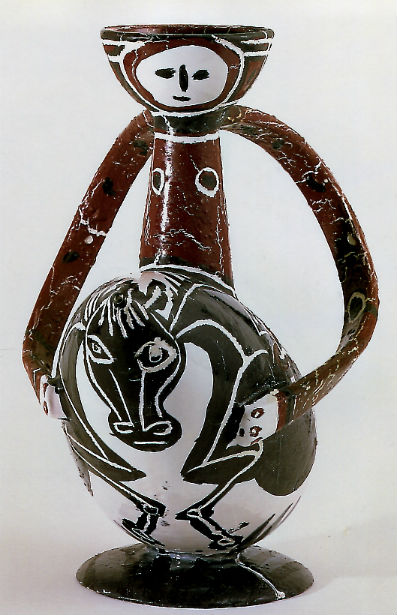

Picasso, Man Riding a Horse, 1951

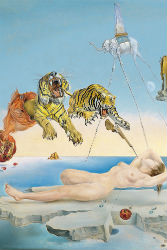

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Nine Chapter 15

You jump in with a question for Diego:

̶ Would you agree that Picasso’s ceramics are the best things he did since Guernica?

Diego, a potter by day and a drummer by night, answers:

̶ I would. He lost the spark after that. Except for the erotic drawings!

Zoomorphic vase (wine pitcher)

White earthenware, thrown and assembled, incised, painted with slips, glazed.

Picasso continued to develop his ideas for zoomorphic pots: first, by using the shapes he had originally designed in 1947 in new ways and, second, by transforming existing Madoura shapes into animal forms principally by means of painting. Man Riding a Horse makes use of his own earlier bird form, but the neck and handles of the vessel are now turned into a rider whose horse is painted on the belly of the pot. At the same time, the general form of the vessel reflects its original function as a wine pitcher.

Picasso, Man Riding a Horse, 1951

MARILYN MCCULLY ON PICASSO’S POTTERY AND CERAMICS

From Picasso: Painter and Sculptor in Clay, edited by Marilyn McCully (NY: Harry Abrams, 1998), pp. 34-36

All images except ‘Condor’ and ‘Standing Bull’ are scanned from this book. (The text and image above on the ‘Zoomorphic vase’ is, of course, from this same source.)

Picasso, Still Life with Two Fish, 1956

Moulded large round plate

White earthenware, cut, impressed, relief applied, painted with oxides and slips, partly glazed.

A variation on Picasso’s earliest plates were the still-lifes he did in 1953 in the 16th-century Palissy tradition, which contrast the modelling of food in high relief with pre-manufactured, domestic ware.

Large bowl

Red earthenware, modelled, relief applied, incised, painted with oxides and slips on raked ground, glazed.

In this series Picasso used pre-fired, glazed pottery from Madoura’s Louis XV service, either green or ochre-coloured round plates with curved borders, to which he attached the modelled clay. After the application of slips, enamels and glazes, the plates were refired with results that, in some cases, are extraordinary both for the richness of the colours of the food and for the way in which the painted glazes give a watery effect to the surface.

Picasso, Three Fish in Relief, 1957

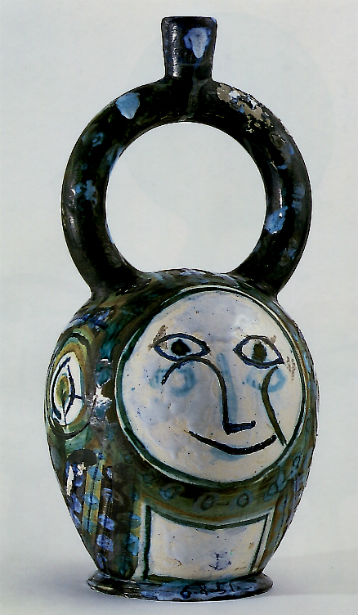

Picasso, Face, 1951

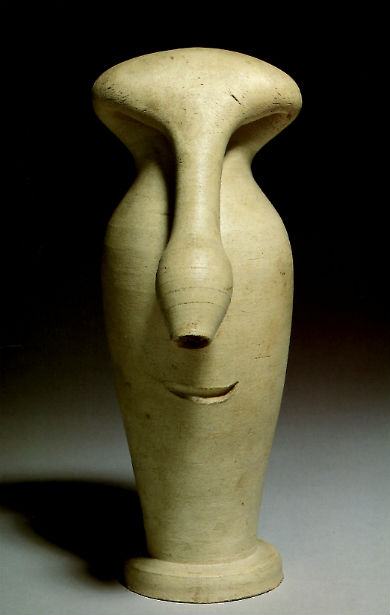

Aztec vase

White earthenware, incised, painted with oxides and slips, glazed.

In the spring of 1949 Picasso had rented an old perfume factory in the route du Fournas in Vallauris, where he worked on sculpture and painting and where he stored the ever increasing number of ceramics that he produced at the nearby Madoura factory. During the next year he intensified the relation of his work in this medium to the classical ceramic tradition, going beyond tanagras and mythological fauns and centaurs to appropriate such traditional shapes as amphorae and casseroles and also working with fragments of brick and of marmites. The fact that the shapes of many earthenware vessels produced in the region had changed little over the centuries reinforced the associations with Antiquity in his own work in clay.

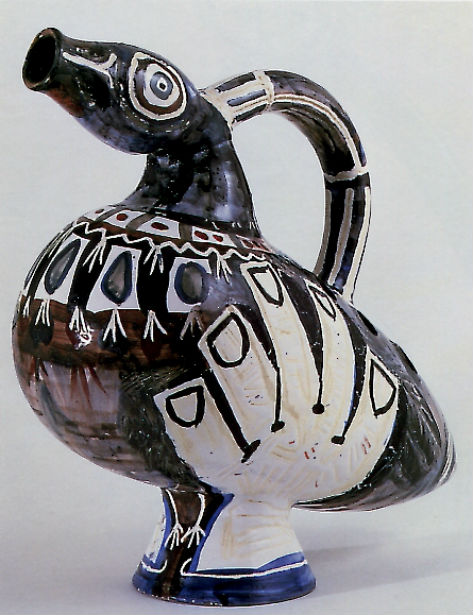

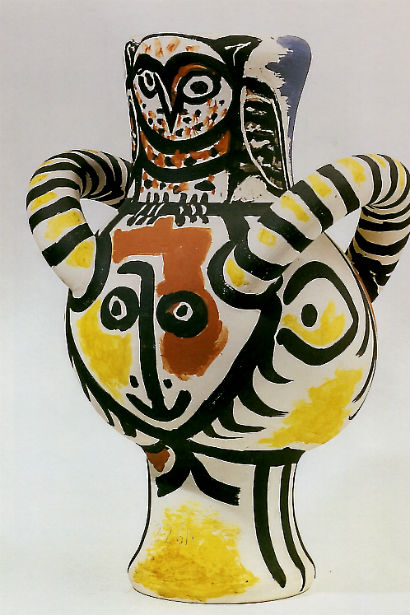

Zoomorphic vase

Fired earthenware, incised, painted with slips, coloured grazed ground.

When Picasso used one of Suzanne Ramié’s designs to create a bird, he granted a new dimension to the zoomorphic shape not only by making marks to denote the bird’s plumage and eyes, but also by adding two painted, grasping hands around the body, curiously recalling the fish-pot he had made with Van Dongen two decades earlier. In general, the transformation of pre-existing Madoura jugs or other vessels by painting took into account specific aspects of the form, which in many cases suggested the animal imagery to Picasso.

Picasso, Hands Grasping a Bird, 1951

Picasso, Head of a Woman, 1948-49

Head of a woman

White earthenware, thrown with elements attached, incised, painted with slips, glazed.

Among the work Picasso produced in 1947-8 was a series of impressive ceramic heads of a woman in which the manipulation of the medium is both humorous—a roll of clay at the back reads as the woman’s hair neatly tucked into a hairnet—and sculptural.

Head of a woman

White earthenware, thrown with elements attached, modelled, incised, painted with slips, glazed.

The principal, volumetric shape was thrown by a craftsman; Picasso then reshaped and incised the malleable clay before painting the heads with slips and covering them with a brushed glaze.

Picasso, Head of a Woman, 1948

Picasso, Blue tanagra, 1948

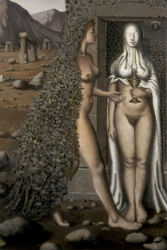

Blue tanagra

White earthenware, thrown, modelled with elements attached, incised, painted with oxides, glazed.

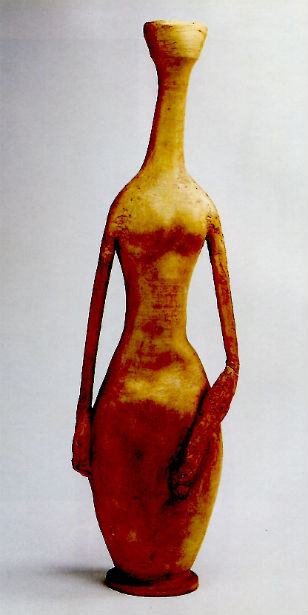

Picasso did a series of drawings in October 1947 for a group of pots in the form of women holding amphorae. They show that, from the outset, the artist had a clear conception of what he wanted to achieve. These partly thrown, partly modelled figures have been associated with Hellenistic terracotta figurines known as tanagras and are among the first works of this type that the artist made at Madoura. In general, Picasso worked on a freshly thrown pot directly on the potter’s banding wheel—the basic shape was always realised by a Madoura craftsman and not by Picasso—and pressed rolls of clay into the form for the arms or manipulated the body of the pot in order to create the figure’s sensual curves. Like their ancient predecessors, Picasso’s tanagras were usually, but not always, painted with slips and sometimes incised; at least one was burnished after firing. Seated figures were created by folding the clay back on itself and pinching it to make hair or facial features; many of these pieces were left unglazed.

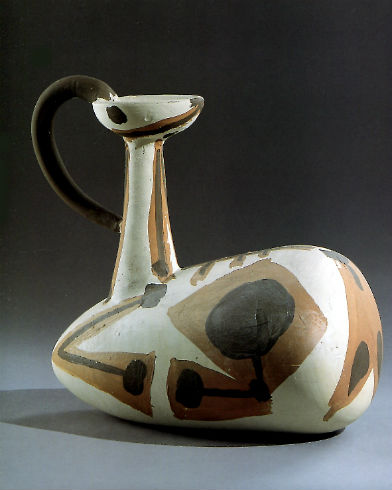

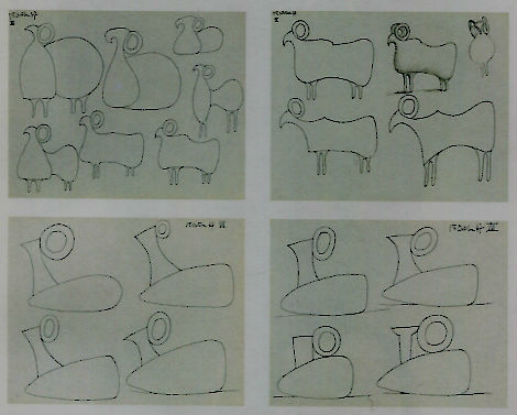

Right from the beginning Picasso was not satisfied with working simply from the standard shapes produced at the Madoura factory: although he relied on Jules Agard to throw his pots—Picasso reportedly had an amazing ability to evoke the forms he wanted with his hands—his sculptural predilections especially affected his ideas for bottles, amphorae and altogether new shapes of his own invention. Ideas for zoomorphic pots fill several sheets of the series of drawings that Picasso had brought with him to the factory, and some of these were realised soon after. As pots they represent some of Picasso’s most effective sculptural ideas in fired clay. They are usually composed of three or four standard ceramic elements: the body is made of a traditional oval vase shape; the foot is the neck of a vase; and handles or spouts form wings, heads and beaks. Eventually, moulds were made from some of these zoomorphic shapes, including the large bird, which was later used by the Ramiés for an edition.

Picasso, Owl and Head of a Faun, 1961

Picasso, Condor, 1947

The zoomorphic pots represent a form of assemblage in that they are created by a subtle rearrangement of the various elements that make up traditional ceramic vessels. Their transformation into works of art occurs both in the new assembly and in the way in which they are painted. The decoration of Condor consists of brown slip on a red ochre ground and only partial glazing. These minimal means produce the effect of wings and feathers and contrast with the real volume of the body of the bird.

Standing Bull (Musée Picasso, Antibes) and Vase in the Shape of a Reclining Kid also appropriate the simplest thrown shapes for sculptural purposes, with schematic decoration supplying essential information.

Picasso, Standing Bull, 1947

Picasso, Vase in the Shape of a Reclining Kid, 1947

Quite a few drawings were made for these pieces, especially for the reclining kid, in which the artist considered its shape from many points of view. In its final form the handle becomes the creature’s horn, while painted decoration suggests the legs folded under its body.

Picasso also did a series of drawings (in late September 1947) for undecorated pots, stacking the thrown and rolled ceramic parts in such a way that they read sculpturally. The significance of the zoomorphic pots is that Picasso first ‘saw’ the form in his mind, with all the given elements, before his hands touched the clay. This is the conceptual procedure he had followed in appropriating a bicycle seat and handlebars to create a bull’s head in 1942, yet the final result in that instance was achieved solely through juxtaposition. In the pots the initial procedure was much the same, but there was an additional stage: not only were ceramic forms treated as found objects, but their sculptural transformation, which involved the addition of modelled elements as well as the ceramic processes of decoration and firing, was also carried out to some degree in the artist’s imagination before their realisation. Nevertheless, the unpredictability of the materials during the firing remained.

Picasso, Studies for Zoomorphic Vases, 1947

Picasso, Standing Woman, 1948

Picasso also made reference to traditional forms when he created figures but, instead of reassembling component parts, he often took thrown vessels or clay slabs and manipulated them by bending and reshaping; in other cases he modelled directly in clay. His tanagras, so-called because of their reference to the Hellenistic terracotta figurines of that name, were usually made by reshaping thrown bottles or vases, some of which were painted in colours that recall Antique decoration. Both the ancient prototypes and the vases themselves have an inherent monumentality and, in spite of their relatively small size, Picasso was able to retain a sense of this in his own figurines. Some of these very sculptural works, such as Standing Woman, were later cast in bronze.

Among the most remarkable pots Picasso created when be began his work in clay in earnest is the unglazed Head, which was made in 1948. The thrown body of the pot is respected, except for the incision of a mouth; but the top is bent over in such a way that the flattened upper part of the vase reads as a forehead, and the neck of the vessel as a trunk or nose. This bending renders the pot useless in terms of its original function; the transformation is decidedly sculptural, while maintaining the immediacy and malleability of its original clay form. This work, too, was later cast in bronze and, in this form, is reminiscent of the giant heads of Marie-Thérèse Walter, composed in part of male genitals, that Picasso had done in the early 1930s.

Picasso, Head, 1948

Christopher Green, Picasso’s ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’

Marilyn McCully, Picasso: Painter and Sculptor in Clay

Picasso Erotique (DVD) [unavailable] | Musée Picasso