LOVE IN FOURTEEN SONGS – V

LAYLA | WHY DO YOU LOVE ME

Eric Clapton—Derek and the Dominos | Shirley Manson—Garbage

Richard Jonathan

LOVE IN FOURTEEN SONGS – THE FIFTH PAIR

Possessive, excessive, exclusive, unique—passion devours. Out-of-time, out-of-the-world, it is ecstatic delirium, a waking dream. ‘Layla’ is a cry of passion, a man’s scream in the night as he woos a woman. ‘Why Do You Love Me’, in contrast, is the passionate cry of a woman who doesn’t want love to disturb her unlovable-girl equilibrium. What do we get by juxtaposing them?

LAYLA

Eric Clapton

In ‘Layla’, the would-be lover is ‘on [his] knees’, ‘begging’, about to go ‘insane’, because the beloved, by rejecting his love, has turned his ‘whole world upside down’. The singer’s voice is raw, but it is the guitars, of course, that swell the scream. What exactly does that scream signify? Beyond testifying to the vital necessity, the crucial imperative, of the love relation for the lover, it signifies that for him, the relation protects him from psychic breakdown, from dissolution as an individual.

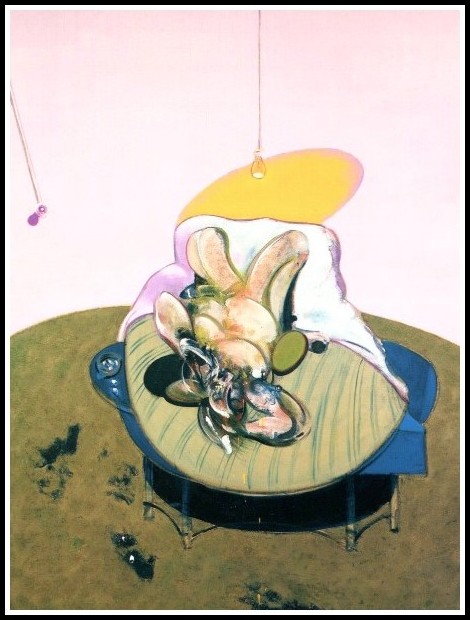

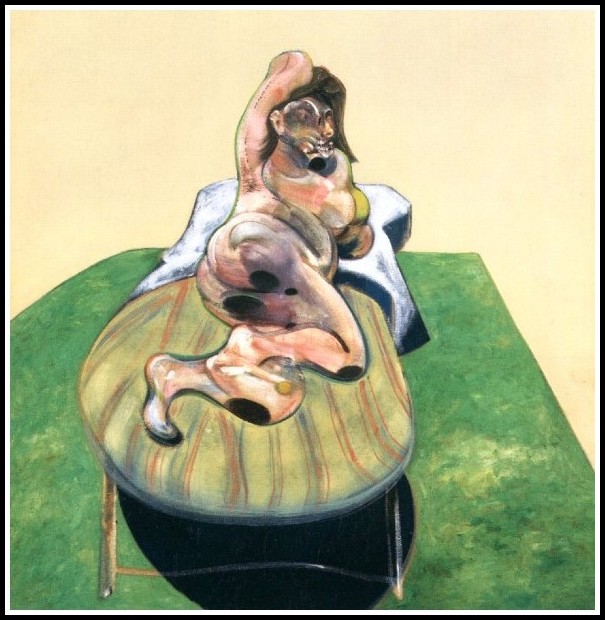

Francis Bacon, Lying Figure, 1969

The majesty of the music, however, the nobility of the song, makes it clear that, however strong his passion, the lover will not abase himself further, will not accept relegation to the role of ‘shadow of your dog’ (as in the Jacques Brel song, ‘Ne me quitte pas’). This refusal of ravishment, this triumph of dignity in despair, is it something men, when seized by passion, are more capable of than women? The evidence from both literature and psychoanalysis suggests that this is indeed the case. Or is it perhaps that men, when the object of passion becomes their last redoubt, their final barrier against breakdown, are more apt to keep themselves together through art? It is not to cede to essentialism to suggest, once again, that the evidence supports such an argument.

Francis Bacon, Henrietta Moraes, 1966

How to interpret the long coda to Layla? An elegy to passion spent, I see it as the lover projecting himself into a future where, having alienated himself in the beloved, he finds himself again. There’s a certain elation in the sadness—no longer under the sway of his obsession, free of its tyranny, the lover can live again—and a self-soothing quality to the music that, of course, only forestalls the emptiness to come: no-one escapes passion unscathed.

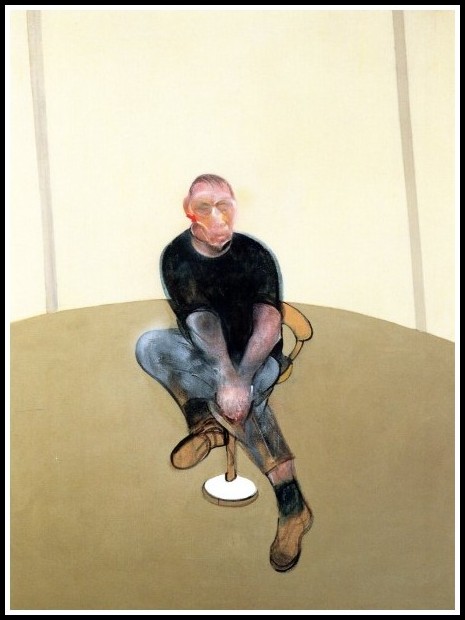

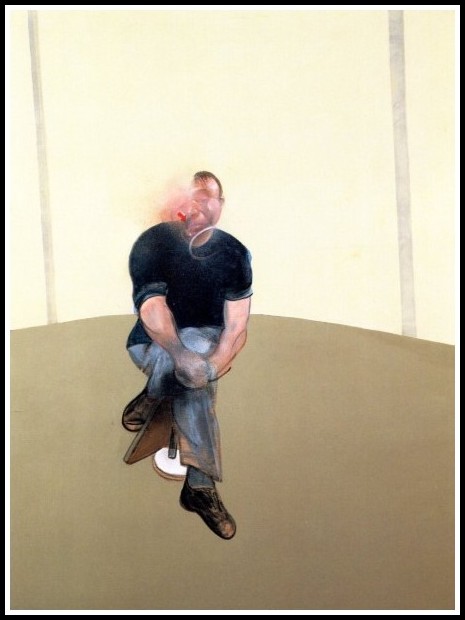

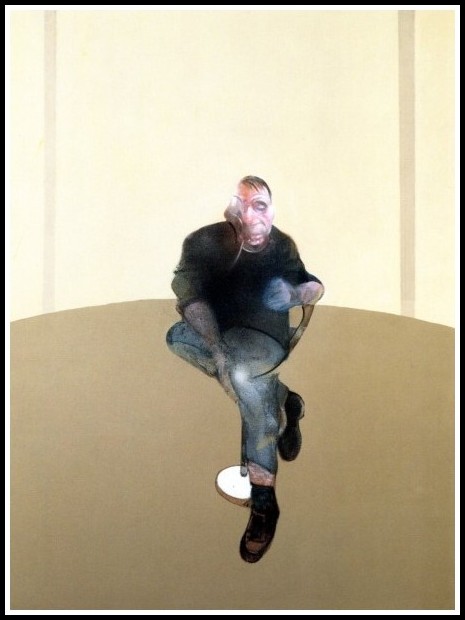

Francis Bacon, Study for Self-Portrait – Triptych – I, 1985-86

Having been consumed in the fire of the verses, if we dwell on the coda, we see that passion can be construed as an attempt to renew oneself, as a quest for rebirth. And therein lies the paradox of passion: the lover loses himself (herself) in order to find himself (herself) again. A phoenix from the fire. Of coure there is no guarantee of such an outcome: ‘Everything depends upon how near you sleep to me’, as Leonard Cohen puts it in ‘Take this Longing from My Tongue’. Or, more prosaically, on one’s courage and self-respect. Indeed, one can just as well emerge from the fire a zombie as a phoenix.

Francis Bacon, Study for Self-Portrait – Triptych – II, 1985-86

‘We are only alive because we desire, yet in our desiring we are obscure to ourselves’: This Freudian principle, articulated in these terms by Adam Phillips, offers, as I have tried to demonstrate, a key to interpreting ‘Layla’. The song (including the coda, critical in this reading) shows that becoming oneself is a work-in-progress, that one is never done with differentiating oneself, and that passion, in putting into play once again absence, loss and otherness, demand for love and demand for recognition, enables one to pursue the business of living in a more dynamic way: ‘He not busy being born is busy dying’ (Dylan).

Francis Bacon, Study for Self-Portrait – Triptych – III, 1985-86

LAYLA

Eric Clapton—Derek and the Dominos

What’ll you do when you get lonely

But nobody’s waiting by your side?

You’ve been running and hiding much too long

You know it’s just your foolish pride

Layla

You’ve got me on my knees

Layla

I’m begging, darling, please

Layla

Darling, won’t you ease my worried mind?

I tried to give you consolation

When your old man had let you down

Like a fool, I fell in love with you

You turned my whole world upside down

Layla

You’ve got me on my knees

Layla

I’m begging, darling, please

Layla

Darling, won’t you ease my worried mind?

Let’s make the best of the situation

Before I finally go insane

Please don’t say we’ll never find a way

And tell me all my love’s in vain

Layla

You’ve got me on my knees

Layla

I’m begging, darling, please

Layla

Darling, won’t you ease my worried mind?

WHY DO YOU LOVE ME

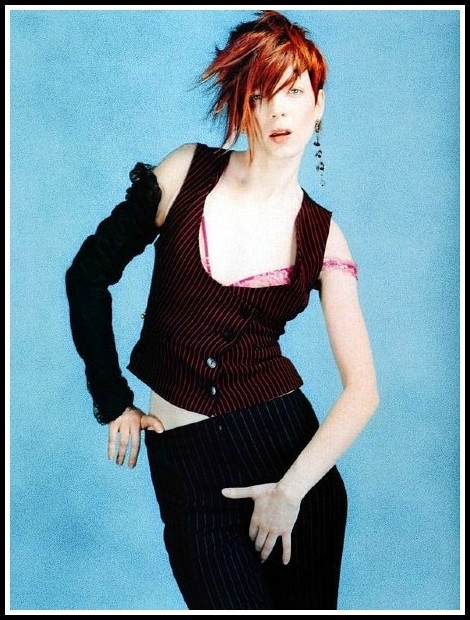

Shirley Manson, 2001

In ‘Why Do You Love Me’ the woman’s passionate refusal of her suitor’s love is a sign of her awareness of how disturbing her acceptance of it would be. Passionately, she refuses to enter into passion, to fall in love. She is tempted—‘You’ve still got the most beautiful face’—but ‘it just makes me sad most of the time’. That her would-be lover may be ‘sleeping with a friend’ of hers (vicarious consummation?) she doesn’t make much of. What she dwells on instead is her ugly-duckling, bad-girl persona: ‘I am not as pretty as those girls in magazines’, ‘I’ve done ugly things, and I have made mistakes’, ‘I am rotten to my core if they’re to be believed’ and ‘Now I’ve held back a wealth of shit, I think I’m gonna choke’.

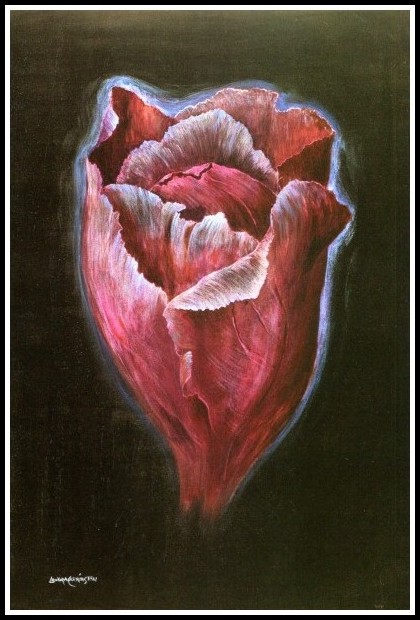

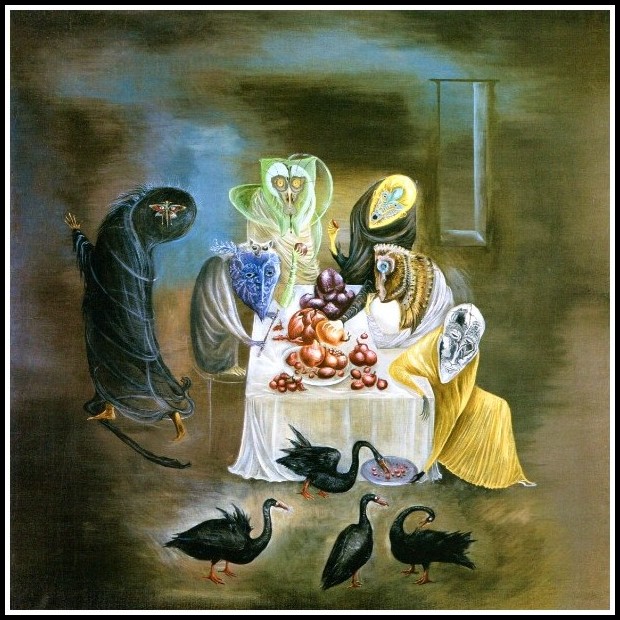

Leonora Carrington, Cabbage, 1987

Whereas the would-be lover in ‘Layla’ is desperate—desperation being the condition for descending into the blindness and self-renunciation of passion—the beloved in ‘Why Do You Love Me’ is bent on maintaining her equilibrium and refuses to be drawn into the dream. And yet, something in her wants to give up control, to let go, for why else would the suitor’s love be ‘driving [her] crazy’?

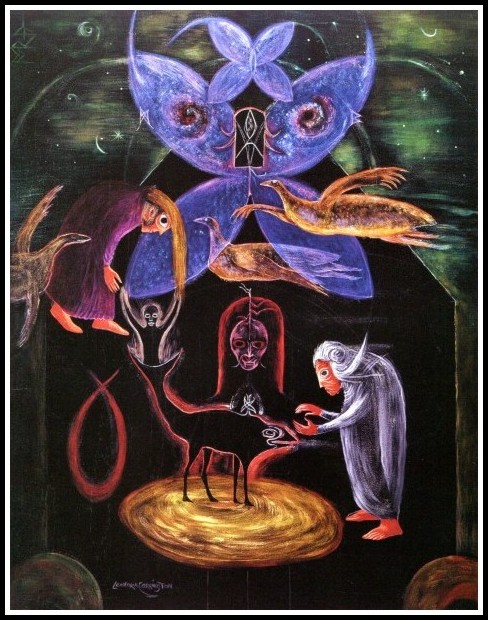

Leonora Carrington, Night of the 8th, 1987

The would-be lover, according to the beloved, is ‘sick of all the rules’ (what rules?) and the beloved is ‘sick of all [his] lies’ (what lies?). I’m not convinced. This strikes me as a rationalization of her fear of falling in love. She is ‘standing in the shadows’, she doesn’t ‘feel good’; something inside her, I sense, wants to let love in, but she fears the havoc it would wreck, the shattering of her equilibrium, and so to ward off love (when the rationalizations for rejecting it don’t suffice), she indulges in some obsessive-compulsive ritual she doesn’t care to specify, content to repeat ‘I get back up and I do it again, I get back up and I do it again, I get back up and I do it again’. Do what? Self-mutilation? Cutting (‘Bleed Like Me’)? Whatever it is, it takes us deeper into the woman’s depths, there where desire chooses a mask for the self to present to the other, there where the woman negotiates ambiguity. Her stance is not ‘foolish pride’ but self-protection.

Leonora Carrington, Giantess, 1950

Where the man in ‘Layla’ screams, in effect, ‘Why don’t you love me?’, the woman in ‘Why Do You Love Me’ screams the opposite: ‘Why do you love me?’. What I’m suggesting is that the two screams are not as opposite at they seem. When the woman sings ‘Nothing ever came from nothing’, she is reproaching herself for ‘the words stuck in [her] throat’, for not clearing out her ‘shit’ and risking love (the one implies the other). Indeed, while she revels in her identity as an outsider, she yearns for the ‘insiderhood’ that comes with loving and being loved. For the rebel, then, for the outsider, love poses a threat to identity. It’s hard, always being against; it’s hard, always being the Other. Yet when the outsider is well in her rebel skin, it’s safer being a spy in the house of love than to come in from the cold.

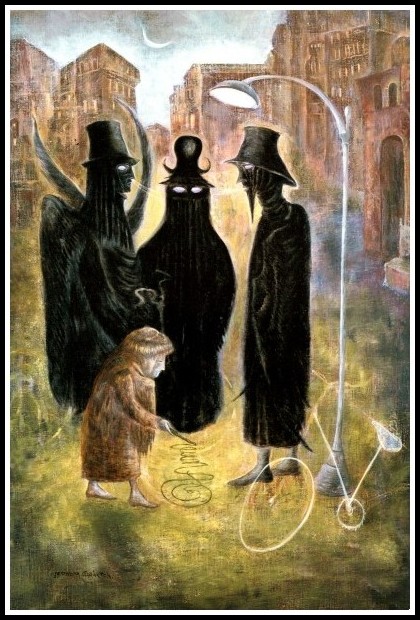

Leonora Carrington, Tribeckoning, 1983

The valence of passion is bipolar: one can be as passionately against something as for it. The heroine of ‘Why Do You Love Me’, as I have tried to demonstrate, is torn between the two poles, and it is this state of in-betweeness that accounts for the violence of her passion: she wants out of her state of suspension, but can neither fully accept nor reject either love or hate. This frustration is the sense of her scream.

Leonora Carrington, Lepidopteros, 1969

WHY DO YOU LOVE ME

Shirley Manson—Garbage

I’m no Barbie doll

I’m not your baby girl

I’ve done ugly things

And I have made mistakes

And I am not as pretty as those girls in magazines

I am rotten to my core if they’re to be believed

So what if I’m no baby bird hanging upon your every word

Nothing ever smells of roses that rises out of mud

Why do you love me

Why do you love me

Why do you love me

It’s driving me crazy…

You’re not some little boy

Why you acting so surprised?

You’re sick of all the rules

Well I’m sick of all your lies

Now I’ve held back a wealth of shit

I think I’m gonna choke

I’m standing in the shadows

With the words stuck in my throat

Does it really come as a surprise

When I tell you I don’t feel good

That nothing ever came from nothing, man

Oh, man, ain’t that the truth

Why do you love me

Why do you love me

Why do you love me

It’s driving me crazy…

I get back up and I do it again…

I think you’re sleeping with a friend of mine

I have no proof

But I think that I’m right

You’ve still got the most beautiful face

It just makes me sad most of the time

I get back up and I do it again…

Why do you love me

Why do you love me

Why do you love me

It’s driving me crazy…

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2022 | All rights reserved

Comments