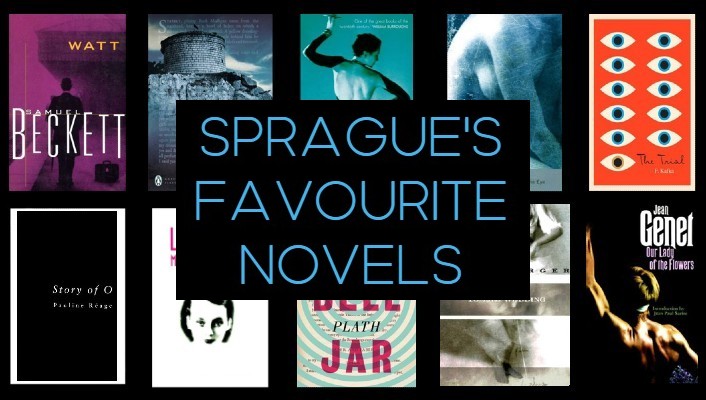

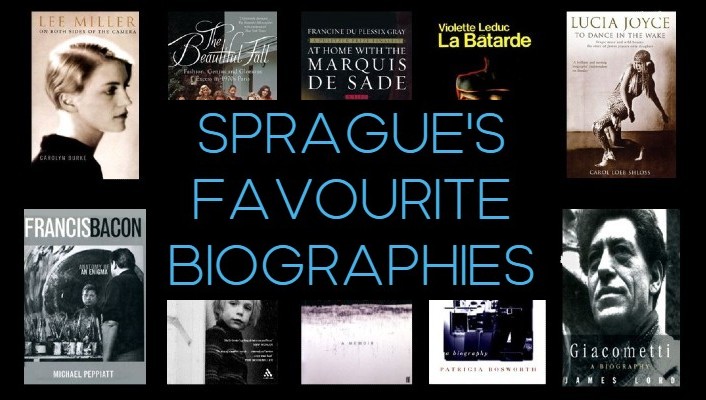

SPRAGUE’S FAVOURITE BIOGRAPHIES AND MEMOIRS

THE HERO’S ‘SELF-PORTRAIT’ IN TEN BIOGRAPHIES & MEMOIRS

This list is an item in the ‘self-portrait’ that Sprague gives Marietta as they part. (He’s the hero, she the heroine, of Mara, Marietta.) Following the excerpts from MM, I present the opening paragraphs of each book on the list.

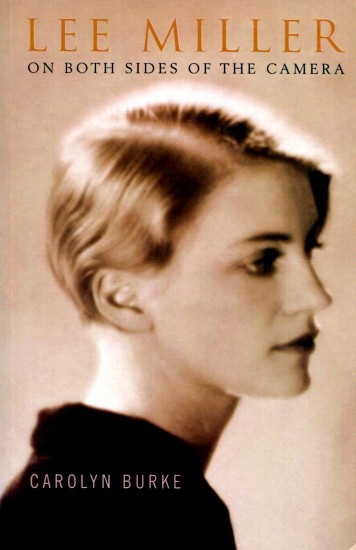

Burke, Lee Miller

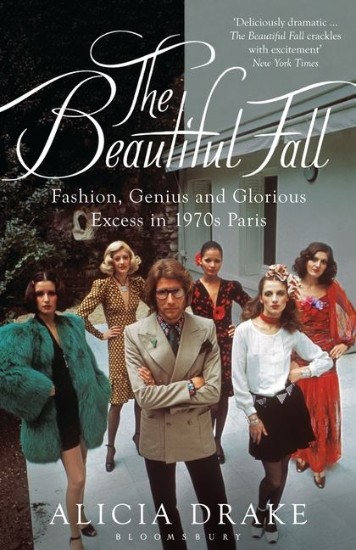

Drake, The Beautiful Fall

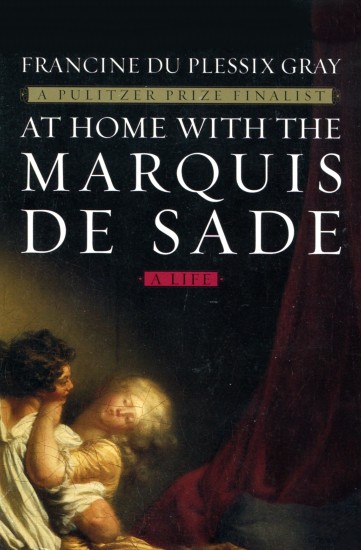

Du Plessix Gray, Sade

Leduc, La Bâtarde

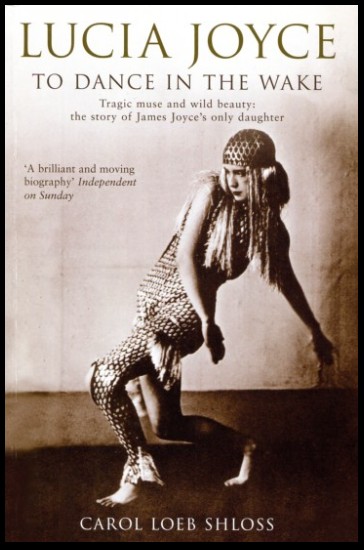

Shloss, Lucia Joyce

Peppiatt, Francis Bacon

Breytenbach, Dog Heart

Gordon, The Café…

Bosworth, Diane Arbus

Lord, Alberto Giacometti

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 6

I reach into my jacket pocket and take out my notebook.

̶ I’ve made a portrait of myself.

I rip out a page and hand it to you.

̶ Will you keep it for me?

You peruse the page.

̶ All right, Sprague. I’ll do that.

MY FAVOURITE BIOGRAPHIES AND MEMOIRS

1. Dog Heart, Breyten Breytenbach

2. The Café after the Pub after the Funeral, Hattie Gordon

3. La Bâtarde, Violette Leduc

4. Giacometti, James Lord

5. Diane Arbus, Patricia Bosworth

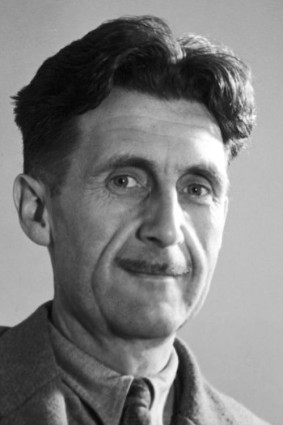

6. Lee Miller: On Both Sides of the Camera, Carolyn Burke

7. Lucia Joyce: To Dance in the Wake, Carol Loeb Shloss

8. At Home with the Marquis de Sade, Francine du Plessix Gray

9. The Beautiful Fall: Yves Saint Laurent and Karl Lagerfeld, Alicia Drake

10. Francis Bacon: Anatomy of an Enigma, Michael Peppiatt

̶ A good self-portrait. But you’ve left it unsigned.

̶ After coming so far for beauty?

Playful, imploring, pensive: your heart in the mirror of your eyes. You fold the paper and put it in your bag.

̶ I’ll keep it. Always. But I don’t need it: I know who you are.

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Seven Chapter 2

Jagged stalks, dusted with snow, recede to a row of bare trees marking the horizon: On both sides of the highway, stubble fields stretch out.

̶ Do you know Leopardi, Sprague?

̶ Yes. Do you?

̶ No.

̶ He’s the brother I never had. I feel very close to him.

̶ Really? Tell me about him.

Claude Lorrain, Peasants Returning, 1637

And thus I came to speak of my beloved Giacomo, of his early understanding that life is nothing but a process of losing: ‘The only people who truly live until their death are those who remain children all their lives.’ I spoke of his pitiless mother, haunted by a sense of sin, incapable of touching her children. I spoke of the boy bent over his books, freezing in his father’s library. Homer and Virgil, Dante and Tasso, Seneca and Cicero: These were Giacomo’s intimates. I spoke of his overwhelming longing for the tenderness of a woman, a tenderness he would never know. Intelligent enough to appreciate his genius, vulnerable enough to be kind: He never met such a woman. His scoliosis, the hump on his back, was but the visible sign, I asserted, that he’d been marked out for sorrow. And thus he was hurt into poetry. As you warmed to my portrait, I spoke of Leopardi’s ethics of lucidity, his refusal of abstraction, his recognition of the individual as an absolute. His poetry, I explained, in restoring presence to things, creates a silence in which memory can speak. Suffering, mourning and solitude—yes, but in a graceful moon on a quiet night there is the promise of a woman and a shared life: Leopardi is the poet of tenderness.

Claude Lorrain, View of La Crescenza, 1649

̶ The brother you never had, hey?

Your eyes shine and I see mine in them: I want to wrap my arms around you, I want to press your body to mine. Or just fall down at your feet.

Iris Origo, Leopardi: A Study in Solitude

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 9

We ask Berglind about her teaching, about how her lecture went.

̶ Good, she says. It was on William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement. The work is so beautiful, the students always take to it.

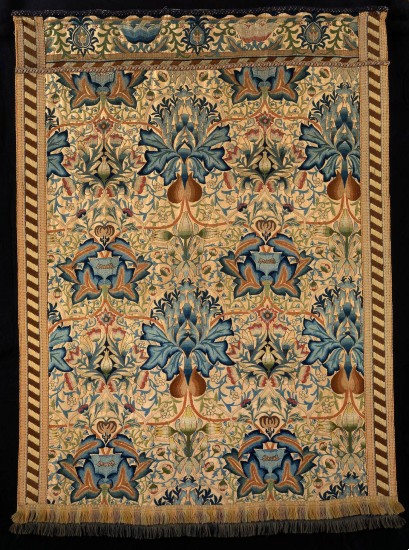

William Morris, Artichoke Wall Hanging, 1877

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

This leads to a discussion on the Pre-Raphaelites. Anna and Gudrun had been devouring Begga’s books on the subject, so I speak not about the paintings but about the artists and models. The twins lap up the anecdotes, and are particularly moved by the story of Lizzie Siddal, the drowned Ophelia in Millais’ painting: Insufficiently educated to become a governess or teacher, too talented and intelligent to settle for factory work or shop assistant, she built a career as a model for the Pre-Raphaelites. Rossetti fell in love with her, but the marriage that would give her a social existence was repeatedly put off. To make her less lower class, to give her the opportunity to cultivate herself, Rossetti wanted her to give up modelling, or rather to pose only for him; the sole alternative to marriage would then become impoverished spinsterhood. Lizzie did give up modelling, seeking to elevate herself in society, but not before posing for Millais: Stretched out in a bathtub with oil lamps underneath to heat the water, she posed as the drowned Ophelia. The last session lasted five hours, the oil ran out in the lamps; Lizzie was chilled to the bone, but did not complain: Her capacity to give herself up completely is what makes the painting so convincing. Finally married to Rossetti, she became pregnant; the child, however, died in her womb. Lizzie then took an overdose of opium and alcohol and killed herself.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Regina Cordium, n.d.

̶ It’s horrible, how hard it was for women to be independent in those days, Gudrun says.

̶ Yes, her father concurs, thank God things have changed.

Then Begga says:

̶ I didn’t know that story, Sprague; thanks for telling it.

̶ Such stories sustain me. I’m not sure why.

̶ Interesting. Would you know why, Marietta? Begga asks.

You look into my eyes: I give you my blessing.

̶ Sprague does read a great deal of biography. I think it simply takes him out of his isolation, gives him a feeling of connection. An artist is always an outsider. It can get very lonely, no matter how much you are loved.

Gudrun interjects:

̶ Don’t be lonely, Sprague! I love you.

̶ Me too! Anna says.

̶ Well, thank you. Such love calls for a celebration: Will you help me write a song after supper?

̶ A song for Seedy Friedrich?

̶ Yes, if it’s good enough.

̶ We will, we will! the twins exclaim together.

I look at their parents, each in turn, as if to apologize—for what, I don’t really know.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Paolo and Francesca da Rimini, 1867

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 11

On a long, low-lying sofa, in a pocket of light from a paper lantern, you sit opposite me, one leg folded under you, your Mata Hari in your hand. How is it that your black stretch blazer, so perfectly fitted to your body, takes nothing away from your air of languid abandonment? Just as the thought crosses my mind, you stand up, take it off, and resume your position. Your grey suede boot on the olive-green leather, your black camisole and burgundy pants, the way you sip your drink—is it that that has turned your languid abandonment into a positively exuberant lassitude?

John Singer Sargent, Madame Gautreau Drinking a Toast, 1882-83

The bar is surprisingly full for a Thursday; the local crowd is mingled in with the foreign guests. Look! In the night sky the lanterns glow: a Magritte effect of the glass. You ask me about Mata Hari. (You take it for granted now that I’m a walking dictionary of biography.) So I tell you the story of Margaretha Zeller, the Dutch woman who mastered the art of femininity and was murdered for it. I tell you of her attraction to men who could fascinate her the way her father did; I tell you that it was in the Dutch East Indies that she became the ‘eye of the day’.

Mata Hari | Charles Reutlinger, 1905 | BnF Images

Sipping my blend of spirits, spices and juices, I tell you that in the context of the war, a woman who travels widely and sleeps with whoever she wants to simply couldn’t be tolerated. The French convicted her on no evidence whatsoever. She had the effrontery to be shameless, and she paid for it with her life. And then I segue into the story of another Dutch woman, one I really admire: Xaviera Hollander. I tell you that she too had an adored, dashing father; that she too spent time in Indonesia and in a transit camp before becoming the free woman who was the Happy Hooker. ‘Let’s try to visit her the next time we’re in Amsterdam’, I’m just about to say, and then I remember that we’ll never be in Amsterdam together again.

Mata Hari | Charles Reutlinger, 1905 | BnF Images

Marietta, how can I live in the world knowing you’re in it but having to pretend you’re not? How can I think of you in the past when you will always be present to me? Don’t you see you’re asking the impossible of me?

Love is not a pact, but complicity; only thus can we find what is profound in pleasure: In bed, once again, you proved it to me.

John Singer Sargent, The Hon. Clare Stuart Wortley, 1923

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

LA BÂTARDE

Violette Leduc (Derek Coltman, translator)

Violette Leduc, La Bâtarde, 1964

My case is not unique: I am afraid of dying and distressed at being in this world. I haven’t worked, I haven’t studied. I have wept, I have cried out in protest. These tears and cries have taken up a great deal of my time. I am tortured by all that time lost whenever I think about it. I cannot think about things for long, but I can find pleasure in a withered lettuce leaf offering me nothing but regrets to chew over. There is no sustenance in the past. I shall depart as I arrived. Intact, loaded down with the defects that have tormented me. I wish I had been born a statue; I am a slug under my dunghill. Virtues, good qualities, courage, meditation, culture. With arms crossed on my breast, I have broken myself against these words.

Reader, my reader, I was writing outside, sitting on the same stone, a year ago. My square-lined writing paper has not changed; the grapevines run in the same lines below the plunging hills. The third row is still covered with a haze of heat. My hills are bathed in the halo of gentleness. Did I go away, have I come back? If so, then living would no longer be merely a slow and ceaseless death as the seconds pass on my wristwatch. And yet my birth certificate fascinates me. Or else revolts me. Or bore me. I read it through from beginning to end whenever I feel the need; I find myself once more in the long gallery as it echoes with the clicking scissors of the doctor attending my birth. I listen, I shiver. We are no longer the communicating vessels we were when she was carrying me. Hereere I am, born, on a register in the town hall, at the point of a town hall clerk’s pen. No nastiness, no placenta; writing, a registration. Who is this Violette Leduc? The great-grandmother of her great-grandmother when all is said and done. Read it again, read it again. This is a birth?

Violette Leduc, Paris, 1964

A mothball with its sulky smell. Women cheat, women suffer. They used to be attractive –so they smooth away their age. I shout mine aloud because I was never attractive, because I shall always have my baby hair. It’s taken me two and a half hours to write that, two and ha half pages of my exercise book. I shall keep on, I shall not lose heart.

The next morning, eight o’clock in the morning of June 24th, 1962. I’ve changed my place, I’m writing in the woods because of the heat. Began my day by picking a bunch of wild sweet peas and picking up a feather. And I complain about being in the world, in a world of trills and thistles. The chestnut trees are slender, the trunks are languid. The light, my light, has been tamed by the leaves. It’s new and it’s the newness of my day.

DOG HEART: A MEMOIR

Breyten Breytenbach

Breyten Breytenbach, Dog Heart, 1999

To cut a long story short: I am dead.

Do you think I’m joking? Am I not lurking behind these rustling words—perhaps a little thicker around the waist, a little darker in the mind? Am I not the writer sitting in the dappled light of the pepper tree, pursing my lips and closing my eyes to the glare of a yellow fire baking the valley?

Mind fumbles for a buried reference; I’m on the verge of remembering the odour of ancient clods. Can one touch the moon?

Yes and no. Obviously I’m writing. Look, I’m even leaning forward to whisper to you. Don’t worry.

There’s nothing I want. I won’t bother you, and I won’t fall down. The ways of the mirror are dark to the eye.

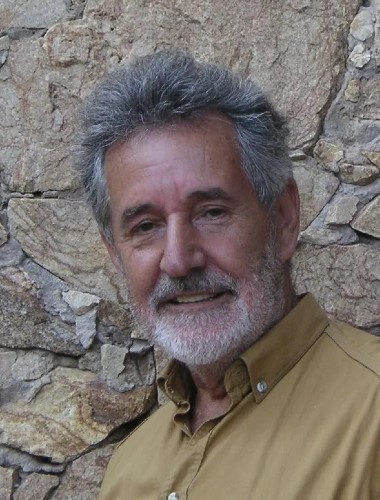

Breyten Breytenbach

But no, when I look into the mirror I know that the child born here is dead. It has been devoured by the dog. The dog looks back at me and he smiles. His teeth are wet with blood. This has always been a violent country. Writing is an after-death activity, a sigh of remorse.

I return to this land now that time has gone away. I try to identify the shadows and talk to the baboons who walk on all fours to avoid being taken for people; the dog growls and I climb the tree, like my grandfather, to watch out for floods and for snakes. Look high, look low!

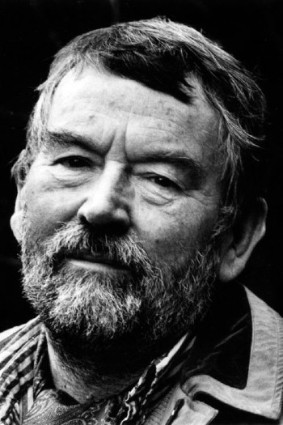

THE CAFÉ AFTER THE PUB AFTER THE FUNERAL

Hattie Gordon

Hattie Gordon, The Café after the Pub…, 2003

It was six years after my mother’s death. My father and his new young family had moved south of the river. I was in his house running a bath when the pitch of the doorbell filled its rooms and hallways. Having seen through the window two policemen walk towards the house, Dad’s childminder shouted up the stairs to me, ‘I think it’s the police.’ I knew what they were about to tell me before I opened the door. I did not need to see their faces, let alone hear their words, because I already knew. It had been a long time coming. The repetition was ruthless, the men of law and order who spread knowledge of death, here once again. The pattern was macabre. There were two of them, only this time they were fully aware. I opened the door, and the figures before me in that blue so dark it is almost black asked if they could come in. I didn’t want them to be the ones to tell me, so I asked, ‘Is it about Gareth?’ ‘Yes, I’m afraid it is, madam.’ ‘Is he dead?’ ‘I’m afraid he is, madam.’

Hattie Gordon at age 7

My brother had killed himself. He was discovered on Tuesday, 13 September 1994 in his flat by Primrose Hill. When they found his body the police noted a newspaper in his living room that was dated for the previous Thursday. They forced open his front door after his neighbours downstairs reported a foul stench emanating from the floor above them. I pictured the police with a crowbar, wrenching open the sealed door, closed from the inside by his own hand. Cracking the wood so that paint flaked off and splintered. He would have had no idea how long his body would be there before it was found. He’d made sure no one else had keys to his flat.

I said something daft to the policemen, about how it must be hard for them to tell people that someone has died. They weren’t interested in responding to me, they wanted to get out of the house. One of the officers told me I would have to telephone the station to find out the details of the case. The case. The case of my brother.

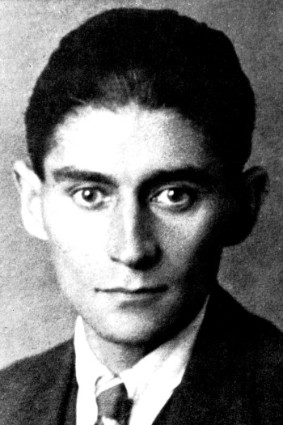

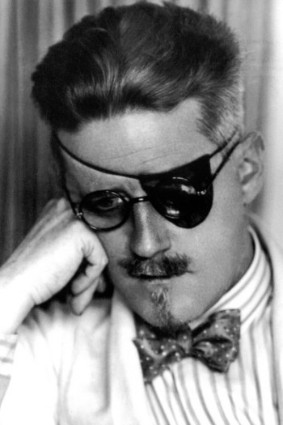

LUCIA JOYCE: TO DANCE IN THE WAKE

Carol Loeb Shloss

Carol Loeb Shloss, Lucia Joyce, 2003

Imagine a cacophony of voices. First came those who knew Lucia: I think that Lucia’s mind is ‘deranged.’ I ran into her on the Champs-Elysées and ‘had never seen her so pretty, so gay, so strangely tranquil.’ ‘That anyone could call her insane seems to me absurd.’ ‘Evidently one is inclined to think that she is more confused than she actually is.’ She was ‘the most normal of the family, tactful, with humor and good sense. A wonderful girl.’ ‘It seems that Lucia, by playing her part so well, has come to be dominated by it and is, in some respects, genuinely out of her wits.’ ‘I did not at the time know that she liked to pose as having been insane, as your sister told me later she did.’ ‘She walked as if she owned the whole bloody world. Her voice was lovely. It bubbled up as if from a deep country well. She had great scope to her.’ ‘Nothing serious happened in Ireland. Everyone who saw Lucia there agreed that she was stronger and less unhappy. But she lived like a gypsy in squalor.’ ‘Lucia went completely mad, and had to be taken out in a straitjacket.’ She should be ‘shut in and left there to sink or swim.’

Next came the voices of the doctors who examined her: ‘There is nothing mentally wrong with her now.’ She’s ‘not lunatic but markedly neurotic.’ ‘There is not much the matter with the girl, and whatever it is, she will soon get over it.’ Lucia is ‘schizophrenic with pithiatic elements.’ ‘Forel said that after seven months he does not feel that he can write a diagnosis; he would not sign his name to a conclusive statement about her.’ ‘He thinks she has made a steady improvement.’ She’s ‘catatonic.’ She’s neurotic. She has cyclothymia. ‘There’s emphatically something to be saved.’

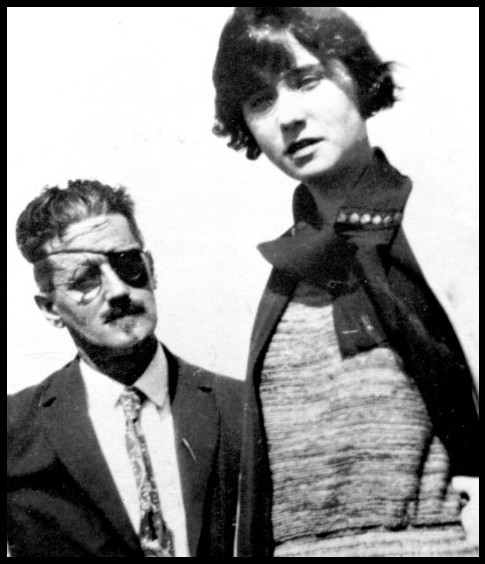

James Joyce with his daughter Lucia

A generation later, the voices of the biographers chimed in: She was ‘a tortured and blocked replica of genius’; she was the ‘shadow of her father’s mind.’ Poor Nora. She had to care for a rude, violent daughter. Everyone had a different opinion about what was wrong with Lucia Joyce. The label that stuck most often was ‘schizophrenia.’ But in one way or another she has sifted down through the years as the mad daughter of a man of genius.

But she was not mad in the eyes of her father. James Joyce disagreed with everybody, and in this disagreement lies the heart of the story told in this book. No matter what happened to Lucia, Joyce did not lose sight of the beauty and talent of his child; he saw the pathos and desperation of her life; he learned from her, and he refused to abandon her. To him she retained the qualities that he had seen in her at birth when he had associated her with Dante’s Beatrice: ‘Once arrived at the place of its desiring, the soul sees a lady held in reverence, splendid in light; and through her radiance, the pilgrim spirit looks upon her being.’ To him she was Lucia the light-giver, the ‘wonder wild.’ Thus whatever else we can say about Lucia Joyce now, so many long years after her death, we know that she was dearly loved. We know that she was greatly talented and that the story of her struggles, amid all its bitter contention, is one of the great love stories of the twentieth century.

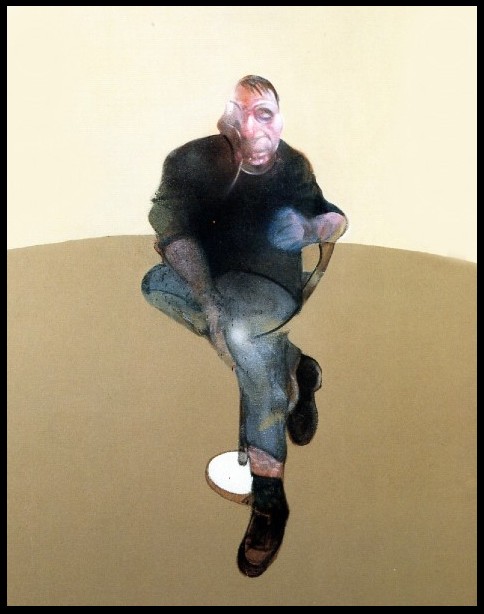

FRANCIS BACON: ANATOMY OF AN ENIGMA

Michael Peppiatt

Michael Peppiatt, Francis Bacon, 1996

Even though he did not often mention his childhood, Francis Bacon acknowledged that it had been central to his whole development. ‘I think artists stay much closer to their childhood than other people,’ he told me on several occasions. ‘They remain far more constant to those early sensations. Other people change completely, but artists tend to stay the way they have been from the beginning.’ When talking amongst friends, the picture he gave of his earliest years and his family was extremely sketchy, but what came inevitably to the fore was his parents’ lack of affection for him, and his own natural waywardness. The episodes which he chose to recount were usually accompanied by a manic laughter that invited his listeners to share his hilarity, as if the whole point of his childhood and his upbringing lay in their absurdity.

Francis Bacon, Study for a Self-Portrait (Triptych), 1985-6

But a distinct underlying bitterness could be heard at times, with resentment welling up at particular memories. The dominant impression Bacon conveyed was that he had been ill-starred from the start by being born into a family which took no interest in him, and a social class in which he felt himself to be an outsider. This unhappy family life was to some extent tempered by its backdrop; and later on, although he was never to return there, Bacon would always speak with affection and admiration about Ireland and the Irish.

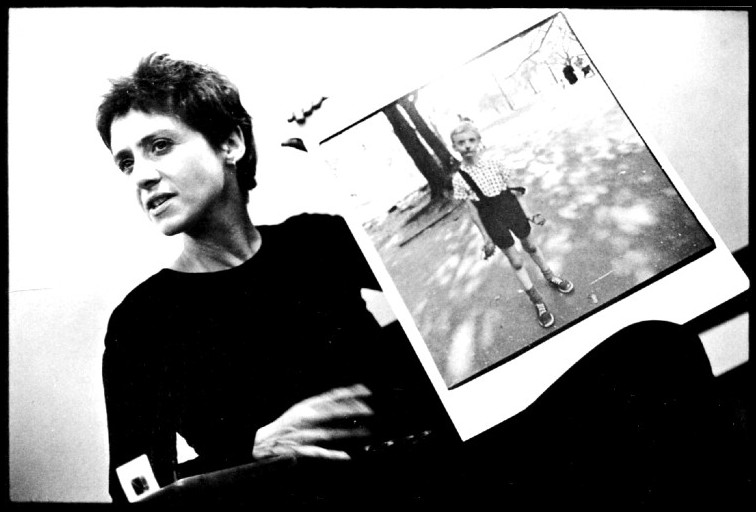

DIANE ARBUS: A BIOGRAPHY

Patricia Bosworth

Patricia Bosworth, Diane Arbus, 1984

As a teenager Diane Arbus used to stand on the window ledge of her parents’ apartment at the San Remo, eleven stories above Central Park West. She would stand there on the ledge for as long as she could, gazing out at the trees and skyscrapers in the distance, until her mother pulled her back inside. Years later Diane would say: ‘I wanted to see if I could do it.’ And she would add, ‘I didn’t inherit my kingdom for a long time.’

Stephen Frank, Diane Arbus, 1970

Ultimately she discovered her kingdom with her camera. Her dream was to photograph everybody in the world. This meant developing tenacity, this meant taking risks, and Diane was always very, very brave; some people even called her reckless. But it seemed perfectly natural, since in her own imagination she believed she was descended from ‘a family of Jewish aristocrats’—given her definition that aristocrats possess a kind of existential courage. As far as she was concerned, aristocracy had nothing to do with money or social position. Aristocracy was linked to a nobility of mind, a purity of spirit, as well as inexhaustible courage. These were qualities Diane Arbus believed to be of utmost importance in life.

ALBERTO GIACOMETTI

James Lord

James Lord, Alberto Giacometti, 1985

The Bregaglia Valley lies deep in a cleft of southeastern Switzerland. A meeting place between north and south, a place much traveled through since Roman days, it has nevertheless retained a character all its own. A telling evidence of this is the religion of Bregaglia’s inhabitants, sternly Protestant amid surrounding Catholics. From the foot of the Maloja Pass the valley slopes steeply downward to the Italian frontier at Castasegna, a distance of twelve miles. It is a region of precipitous slopes, jagged peaks, icy streams, high meadows, and simple villages. Beautiful but austere.

Alberto Giacometti, The Forest, 1950

Before winter’s snows first fall to the valley floor, the sun leaves it. From early November till mid-February, the sheer mountain walls cut off all sunlight, and the coldest time of day or night is high noon, when fiercest cold is driven down to the frost-encrusted depths. ‘It’s a sort of purgatory,’ Diego sometimes said. However that may be, it was there that everything began for the sculptor and painter Alberto Giacometti. It was there that circumstances led him to become an artist, there that they assumed their fullest meaning, there that the allegory of his life pointed its most profound and valuable moral.

THE BEAUTIFUL FALL: YVES SAINT-LAURENT & KARL LAGERFELD

Alicia Drake

Alicia Drake, The Beautiful Fall, 2006

Standing on stage were the three winners of the International Wool Secretariat fashion design competition of 1954. Two of them were young men dressed almost identically: dark suits, dark ties, white shirts, the very image of apprenticeship propriety. Yves Mathieu-Saint-Laurent, as he was called then, was aged eighteen, recently arrived from Oran, Algeria, and winner of the first and third prizes in the dress category. He stepped forward to accept his prizes with all the paddock tremors of a racehorse, one hand leaping up spasmodically to hide one eye, obscuring half the world.

Beside him was Karl Lagerfeld, aged twenty-one, from Hamburg, and winner of the coat category. He talked fast and in French, nervously licking his lips as his words spilled out like marbles. He clasped his hands awkwardly in front of him. At the far end of the group stood Colette Bracchi, winner of the suit category and seemingly the most self-assured of the three.. She would henceforth disappear into fashion oblivion.

These three represented the best of young Paris fashion talent. Poised to enter the rarefied world of haute couture, they were, as the man handing out the prizes told the audience, ‘already on the road to success’. Their winning designs had been picked from an entry of six thousand anonymous sketches, which made Saint Laurent’s feat of having two sketches selected all the more extraordinary. Added to his success was the fact that Yves had come third in the previous year’s competition.

The competition was only in its second year, but already highly prestigous. Its objective was to promote wool in fashion, so the rules stipulated that every design entry should be intended for wool fabric. The jury included Hubert de Givenchy and Pierre Balmain, and the previous year Christian Dior had been a judge. There was substantial prize money but, more importantly, each first-prize winner had their sketch made up into an outfit by one of the Paris haute-couture houses.

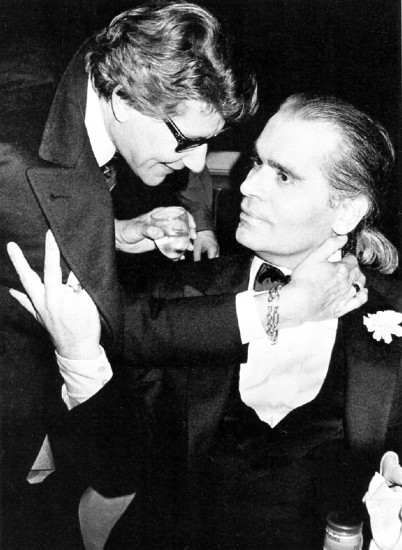

Yves Saint-Laurent & Karl Lagerfeld, Le Palace (Paris), 1983

That meant by the time of the awards ceremony in December the winners were all accornparried on stage by a model wearing their design. Karl’s coat was made of daffodil-yellow wool and followed straight lines. It finished primly on the calf and, as if to compensate, was cut low across the collarbone and then dipped into a V at the back. It was an appropriate coat for a blue-chip wife to wear to lunch.

Yves Saint Laurent’s cocktail dress was pert and enticing, a black sheath that wrapped around one shoulder, exposing the other to a passing caress. A black veil fluttered across the model’s face, suggesting the seductive whimsy expected of a Parisienne. ‘Elegance,’ said the breathless teenage Yves, ‘is a dress too dazzling to dare to wear twice.’

Yves Saint Laurent and Karl Lagerfeld stepped on to the Paris fashion stage together as equals. And yet from the very start Yves walked an apparently charmed path. He was the youngest of the three winners by three years; his first and third prizes in the dress category defined him as a boy wonder; and he was French Algerian, which meant the French could claim his victory as their own. Most subtle and yet most marked was the distinction that Saint Laurent won the dress category and, within world of haute couture, dresses carried utmost prestige.

They would become rivals, but first they were friends, which was hardly surprising, for Yves and Karl had much in common. Both were the only, cherished sons of prosperous, middle-class families. Their fathers were successful businessmen who provided for their families, aspiring wives and bourgeois lifestyles. Both fathers conducted an entirely courteous and caring, if distant, relationship with their sons, which was perhaps characteristic of their generation. Both boys were homosexual and aware of their sexual orientation from an early age. They loved to sketch and in particular they loved to sketch dresses. They were both boys from provinces, dreaming of Paris.

LEE MILLER: ON BOTH SIDES OF THE CAMERA

Carolyn Burke

Carolyn Burke, Lee Miller, 2005

Lee Miller was one of the most remarkable, and under-recognized, photographers of the last century. At their best, her images put head, eye, and heart on one line of sight—to borrow a phrase from her friend Henri Cartier-Bresson. Like him, Lee Miller captured those decisive moments when reality seems to compose itself for the camera, when the visual world speaks. But because she did not pursue a conventional career, her reputation, until recently, has been eclipsed by her legend, and the famous men who helped construct it.

While it is true that Lee Miller’s early work in Paris recalls that of her lover Man Ray, it was uniquely her own—full of startling perspectives and witty surprises. In Egypt, her home in the mid-1930s, her unforced Surrealist eye saw familiar and unfamiliar sights through the skewed lens of her expatriation. In the 1940s, her World War II coverage for Vogue conveyed the urgency of combat, the horror of the death camps, and the war’s impact on ordinary lives—the lateral damage that gripped her long after it came to a close.

That Lee Miller was also one of the most beautiful women of the twentieth-century has made it difficult to evaluate her work in its own right. Her astounding good looks seem to get in the way. For many, her beauty is at war with her accomplishment, as if the mind resists the thought of a dazzling woman who is a first-rate photographer.

Lee Miller, A Strange Encounter, Paris c.1930

One might even say that there are too many portraits of Lee Miller by better-known artists. Edward Steichen launched her as a model; Man Ray photographed her, whole and in parts, as his perversely enchanting muse; Jean Cocteau cast her as the spellbinding classical statue in his film Blood of a Poet; Picasso painted six portraits of her as a Provençal wench whose bare breasts inspire reveries of sexual freedom; Roland Penrose charted his erotic relations with her in a series of paintings that range from ecstatic to melancholy.

Mesmerized by her features, we look at Lee Miller but not into her. We think of her as a timeless icon. To this day, her life inspires features in the same glossy magazines for which she posed—articles explaining how to recreate her ‘look.’ This approach turns the real woman into a screen on which beholders project their fantasies. Looking at her this way perpetuates the legend of Lee Miller as ‘an American free spirit wrapped in the body of a Greek goddess’ (in the words of her friend John Phillips) while underplaying her élan, the imaginative and moral energy that magnetized those who knew her, often to their cost.

In Lee Miller’s time, her admirers were equally spellbound by her beauty, but they also saw her as an incarnation of the modern woman—in the United States of the twenties, as a quintessential flapper; in Paris of the thirties, as a subversive garçonne or a maddeningly free femme surréaliste—one who sparked creativity in others but played the role of muse only when it suited her, and sought, despite her lovers’ objections, to keep her energy for herself.

AT HOME WITH THE MARQUIS DE SADE

Francine du Plessix Gray

Francine Du Plessix Gray, At Home… Sade

The child stood in the palace courtyard, shouting. Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade, a ravishing blond four-year-old, was giving the first public display of his dreadful temper.

‘That is mine!’ he yelled at his playmate, eight-year-old Prince de Condé, a prince of the royal blood. Donatien may have been clamoring for his toy horse, his miniature sword, his skip rope. It could have been one of many objects, but it was the one currently in his friend’s hand, and Donatien, fearing that the little prince would choose to keep it, demanded that it be returned to him that very instant.

Upon being denied his toy, the four-year-old threw himself fiercely upon his dearest playmate, the beloved companion in whose home he had been brought up since birth, and started pummeling the young Prince de Condé’s chest with his tiny fists, smacking the face ten inches above his own, continuing to bellow out his rage, howling urgently for his possession. Young Condé, who as head of the junior branch of the Bourbon family was a prince of the royal blood and already aware of his exalted station, cried out for his friend to stop. Soon the warring pair was surrounded by dozens of palace personnel—gentlemen of the bed-chamber and tutors and governesses, equerries, grooms, and valets, all shouting for the little marquis to desist. It took the strength of several adults to separate the battling children. Young Sade’s voracity, his need to have every appetite instantly indulged—which most humans begin to curb at the age of seven or eight—was a trait this particular boy would seldom in his lifetime be willing to control.

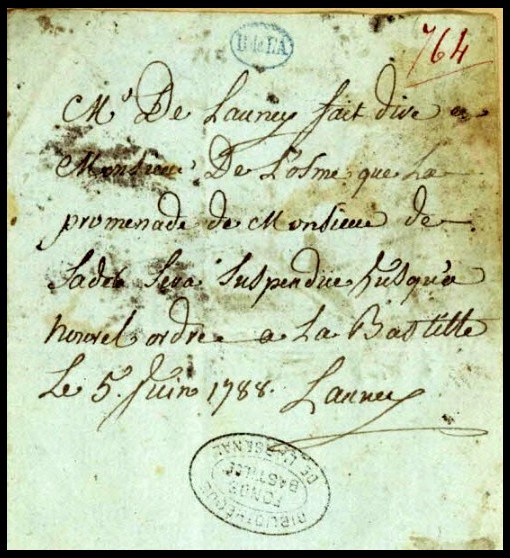

Order suspending prisoner Sade’s right to a daily walk, 1788 | BnF Images

The struggle took place in 1744 at the Condés’ palace, Paris’s largest private residence, whose hundreds of acres of park and scores of superbly furnished rooms overlooked the entire expanse of what is now the Luxembourg Gardens. Born in 1740, the little Marquis de Sade had been brought up in this palace alongside young Prince de Condé, his mother being a relative of the prince’s father and a governess and lady-in-waiting to the prince.

Whether the young noble was bruised or bloodied by Donatien’s blows, or whether just his feelings were hurt, is not known. There is only one fact we are sure of: shortly after this confrontation, the four-year-old Marquis de Sade suffered the first of his many banishments. In the following weeks, he was shunted out of Paris to his paternal grandmother’s home in Avignon, the region of Provence where his ancestors had exercised their feudal rights with legendary arrogance.

The young marquis’s nascent hubris cannot have been diminished by the greeting he received upon his arrival in Avignon. He was met by a delegation of the most distinguished citizens of Saumane, one of the several neighboring villages owned by his father. They came, in the delegation’s own words, ‘to compliment M. Marquis de Sade, son of M. le Comte, lord of this place, on his happy arrival in Avignon, and to wish him long and happy years as his presumptive heir.’ A score of adults bowing, scraping their hats upon the floor, to pay homage to the three-foot-high Donatien: he must have relished it.