I. INTRODUCTION | II. PLATO’S ATLANTIS | III. THE GIRL WHO LIVED IN THE TREE | IV. VOSS | V. CODA

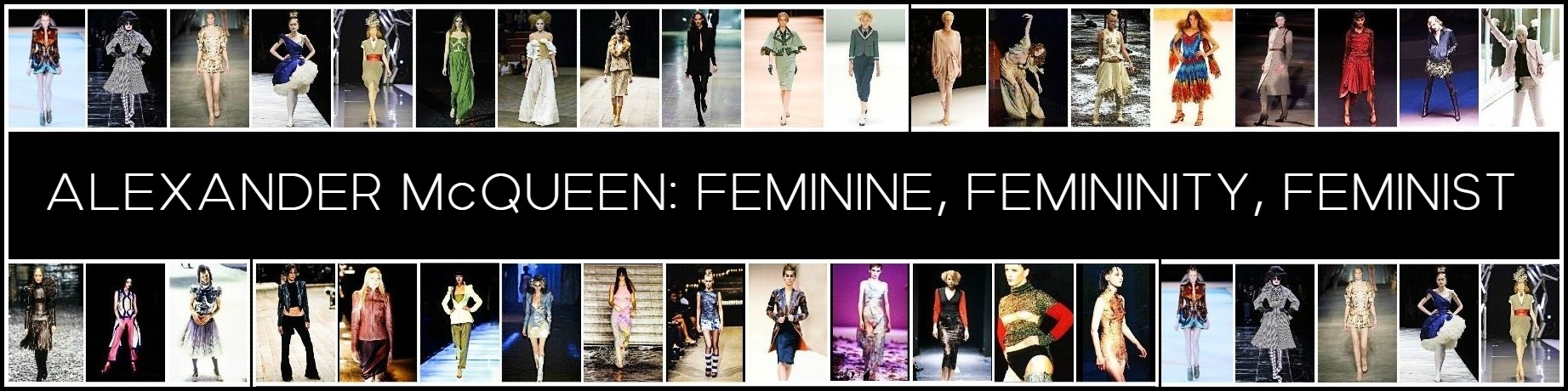

ALEXANDER MCQUEEN: FEMININE, FEMININITY, FEMINIST

A Thematic Analysis of ‘Plato’s Atlantis’ | ‘The Girl Who Lived in the Tree’ | ‘Voss’

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel ‘Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms‘

Alexander McQueen, Le testament d’Alexander McQueen, Loïc Prigent (ARTE DVD 2015)

I. INTRODUCTION

Alexander McQueen, when asked by an interviewer how designing for men is different from designing for women, replied: ‘You can’t really push a man as far as you can a woman, a man will never wear a skirt’. The interviewer, pointing at his suit, says: ‘Yes, it will always be some variation of this’. McQueen confirms, saying: ‘Yeah, it won’t move from that, it will just be proportion and colour and shape that you can play with’. In other words, McQueen finds that in designing for women there is more scope for discovery, for genuine creation, whereas in designing for men, the outcome—some variation of a suit—is generally known. (This was not always the case, of course. Indeed, before the ‘The Great Masculine Renunciation’* that occurred during the eighteenth century, ‘the elegance and richness of male dress equaled and often surpassed that of female dress’**.)

* J. C. Flügel, The Psychology of Clothes (London: Hogarth, 1930), 117-119

** Kaja Silverman, ‘Fragments of a Fashionable Discourse’ (1986) in Shari Benstock & Susanne Ferris, ed., On Fashion (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1994), 183

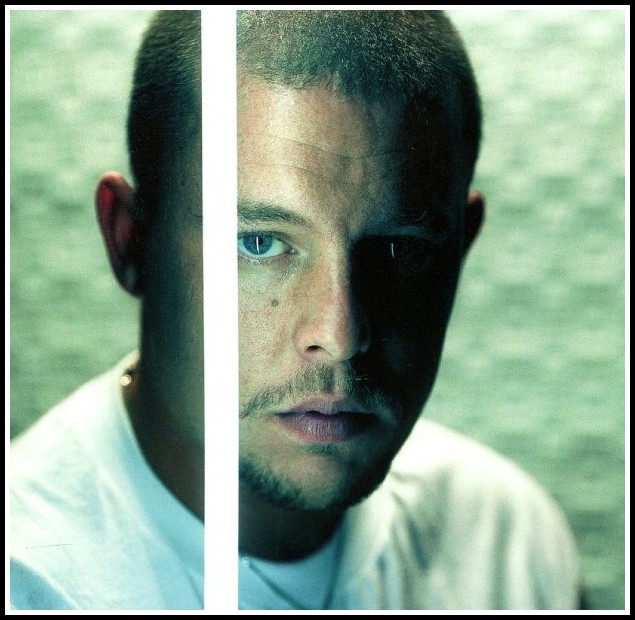

Alexander McQueen | Joseph Cultice, 1999

A woman, then, offers the designer an open-ended journey rather than a fixed terminus, a flow of becoming in which paradox and contradiction are maintained in tension: the very conditions of art. Other artists confirm this feminine bent. In cinema, for example, Fassbinder, Von Trier, Bergman and Almodóvar are but four of the many filmmakers who prefer women as their lead characters (with Fassbinder, in The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant, going so far as to transpose male autobiography into female drama). In this essay, then, the concepts of ‘feminine’, ‘femininity’ and ‘feminist’ will constitute the framework through which I discuss McQueen’s work. Beyond the truism that every male artist necessarily cultivates his feminine dimension in order to create (in this light, the fact that McQueen, Fassbinder and Almodóvar were/are homosexual is merely incidental), I will simply note here that beyond sexuality, McQueen’s art expresses a queer sensibility*.

* Perhaps the best definition of this term is the one provided by David J. Getsy: “‘Queer’ is not an identity. Rather, it offers a strategic undercutting of the stability of identity and of the dispensation of power that shadows the assignment of categories and taxonomies. Artists who identify their practices as queer call forth utopian and dystopian alternatives to the ordinary, adopt outlaw stances, embrace criminality and opacity, and forge unprecedented kinships, relationships, loves, and communities. Artists have used the concept of queer as a site of political and institutional critique, as a framework to develop new families and histories, as a spur to action, and as a basis from which to declare inassimilable difference.”

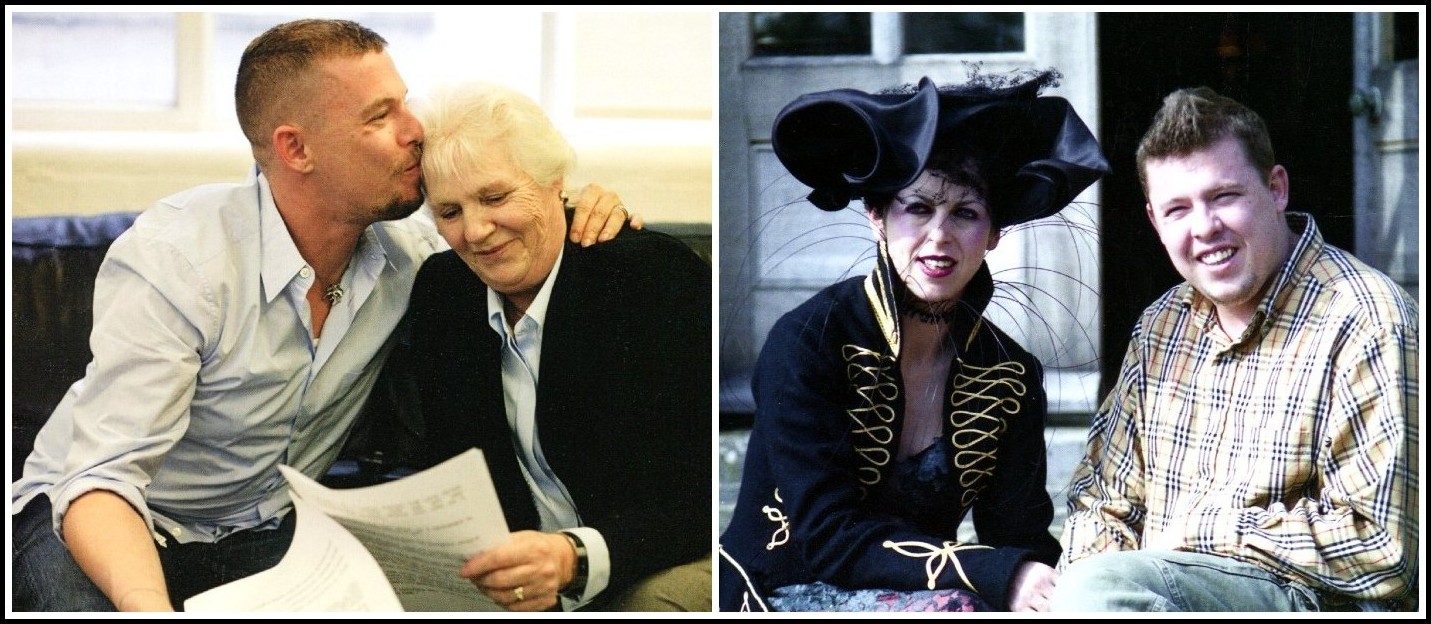

Alexander McQueen & his mother, Joyce, 2004 (Dan Chung, The Guardian) | Isabella Blow & Alexander McQueen, Dante, F/W 1996-97 (Peter Thorn, BBC)

The artist is driven by desire and fascination. He—I’m speaking of male artists—senses the feminine lurking beneath a woman’s femininity, and he knows that however much it escapes him, it also escapes her. It is this complexity of feminine identity that feeds the artist’s obsession, this inexhaustible riddle of what a woman wants. She may not be aware of it, but in exhibiting her femininity, in armouring herself with it, she is erecting a defence against not only her own anxieties, but the man’s as well. This undertow of complicity animates many a flirtation, be it sexual or artistic.

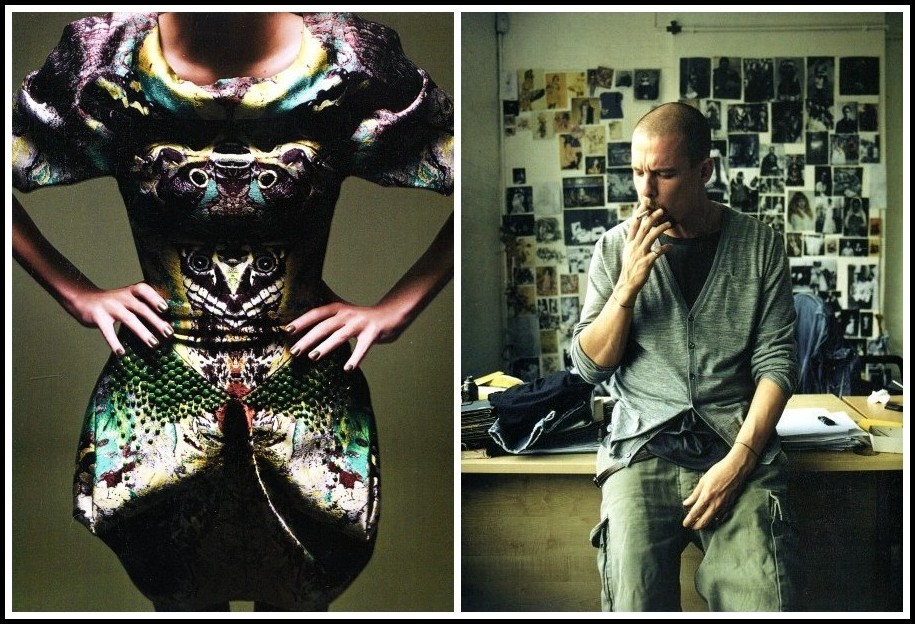

Alexander McQueen, Plato’s Atlantis, S/S 2010 | McQueen in his office, 2004 (Derrick Santini)

Now, those of you versed in psychoanalysis will say:

– Classic Freud.

And I will answer:

– Indeed. So tell me, for each sex, in the interplay of alterity and identity, who is the Other?

The exchange may then unfold as follows:

– Woman is the Other for both men and women.

– Okay, so you also know your Lacan. But we need to have another taste of his teasers before we move on.

– All right.

– Women’s jouissance is of the order of the infinite. They may experience it, but they know nothing about it. Another?

– Yes.

– Women do not lend themselves to generalization: there is not such thing as Woman. One more?

– Okay.

– A woman is a symptom of a man: she can only ever enter the psychic economy of men as a fantasy object (a), the cause of their desire.*

* For a brilliantly lucid discussion of Lacanian concepts in relation to fashion, see Alison Bancroft, Fashion and Psychoanalysis (I.B. Tauris, 2012)

Alexander McQueen, La Dame Bleue, S/S 2008

– All right, so you’ve shone a light on ‘feminine’ and ‘femininity’, but what about ‘feminism’?

– Feminism is about a woman’s self-invention, being author and actor of her life, playing with convention when she can’t opt out of it.

– That’s queer.

– Exactly. A feminist, as I’m using the term here, understands the queerness of femininity and affirms it. Through play she explores the feminine within and the wider world without. In a word, she actively spins her own web—erotic, intellectual, affective, sensual—rather than passively being ensnared in others’ toils.

– So a feminist who assumes her femininity while being (as she cannot help but be) subject to the feminine is a spider in the guise of a fly?

– You’ve got it!

– Okay.

– And that does it for my introduction.

– What’s next?

– A discussion of three McQueen runway shows—Plato’s Atlantis, The Girl Who Lived in the Tree and Voss—in terms of our trilogy.

– Feminine, femininity, feminism?

– Yes. And at the end, a coda.

– All right. Let’s go!

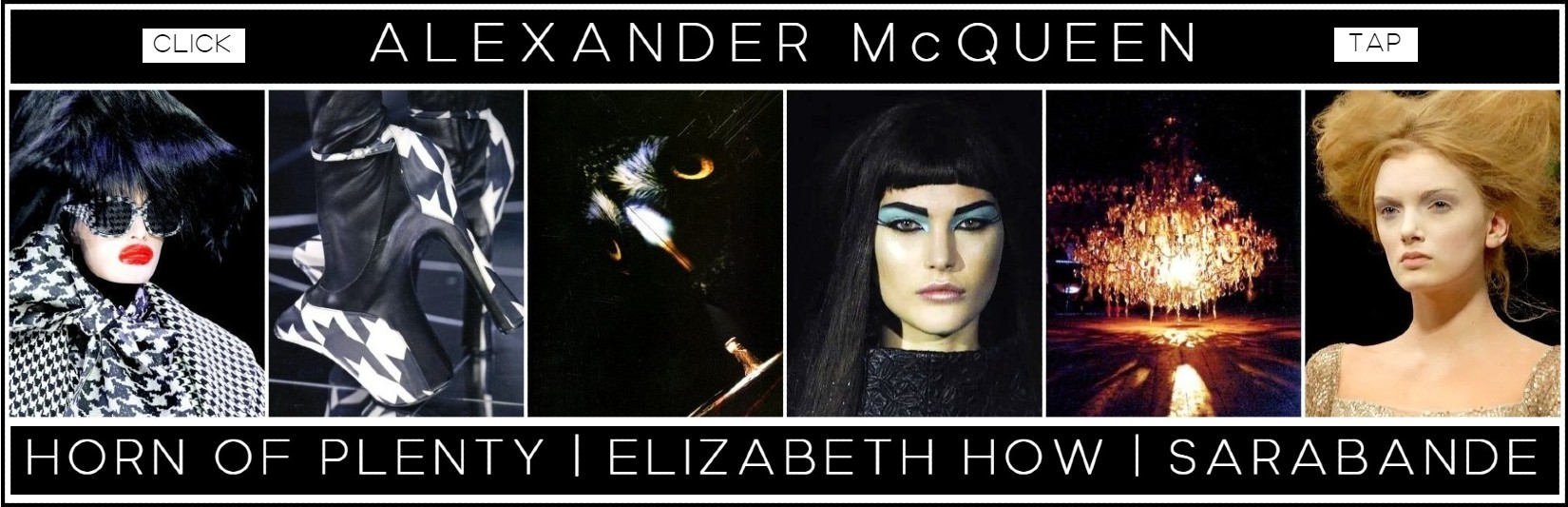

ALEXANDER McQUEEN

Natural Dis-tinction Un-natural Selection, S/S 2009 | In Memory of Elizabeth How, Salem 1692, F/W 2007-08

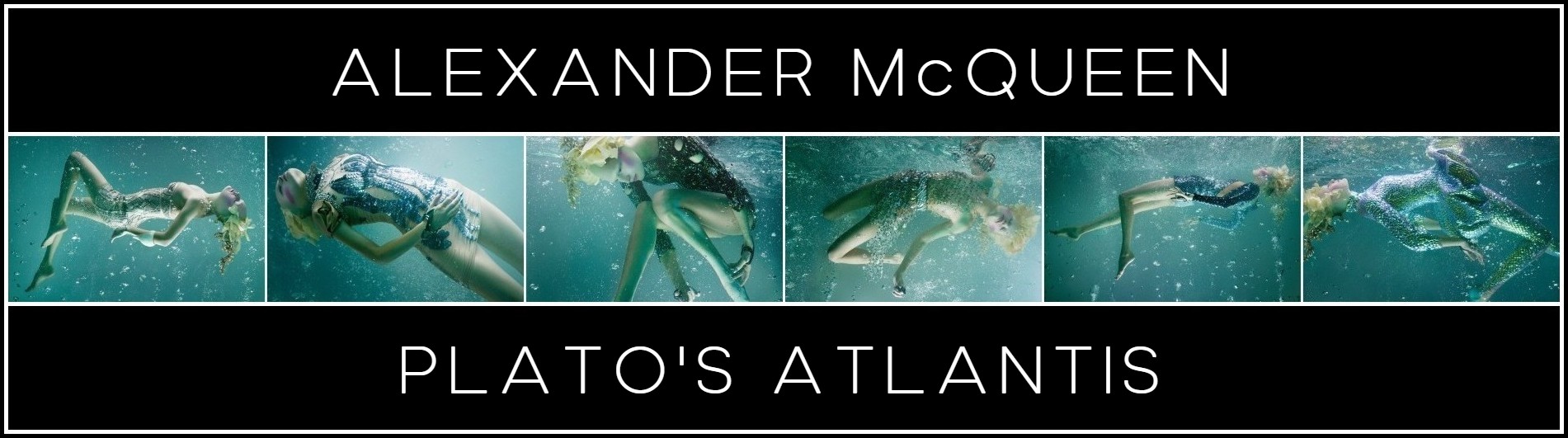

II. ALEXANDER McQUEEN: PLATO’S ATLANTIS | S/S 2010

Palais Omnisports de Paris-Bercy, 6 October 2009

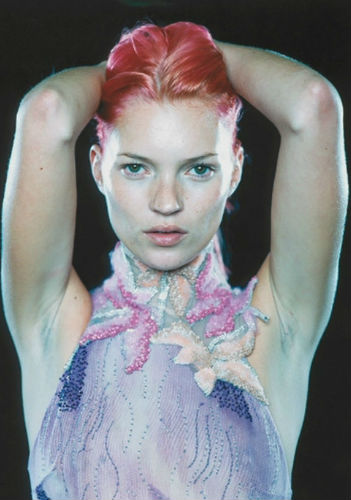

‘The Girl from Atlantis’, Vogue Nippon, May 2010 | Photos: Sølve Sundsbø

All Alexander McQueen’s shows are about the staging of aesthetic emotion, the mise-en-scène of beauty in order to destabilize intellectual, spiritual and bodily certainties. Wielding his scissors, he cuts into the closure of convention and, beyond subversion, opens up possibilities for invention. Never reductive, he assumes duplicity; in a seductive movement of story and concept he uses fantasy to confront us with reality. In a word, McQueen is an artist. Consider his last runway show, Plato’s Atlantis.

Alexander McQueen, A/W 2002 campaign photo | Steven Klein

On a screen backdrop a woman writhes on desert sand as serpents slither across her naked body: the serpent is as fine a vehicle as any to express McQueen’s overarching theme: the generative power of paradox in suspension, of attraction and repulsion held in tension. Indeed, throughout his work, we see the interplay of spirit and nature, soul and libido, instinct and reason, that characterize the serpent, all subsumed under the reptile’s alliance of life’s motive power and the drive toward death.

Alexander McQueen, Plato’s Atlantis, S/S 2010

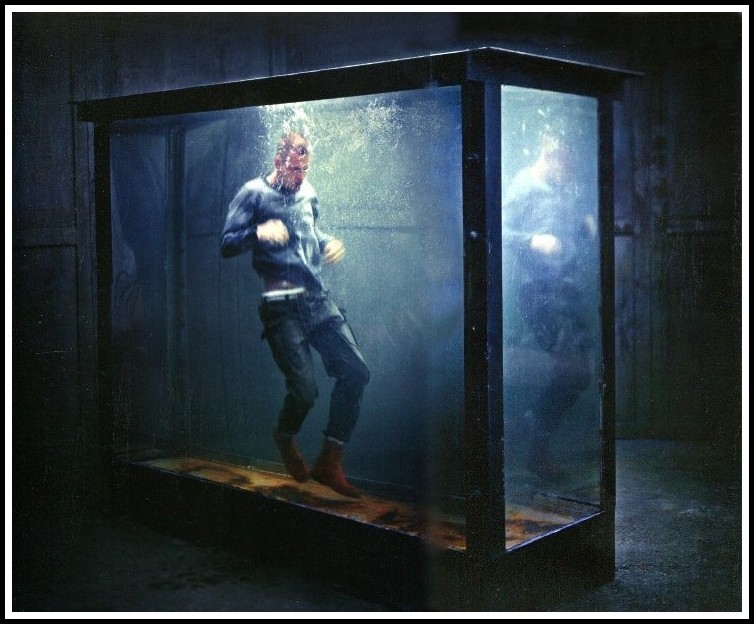

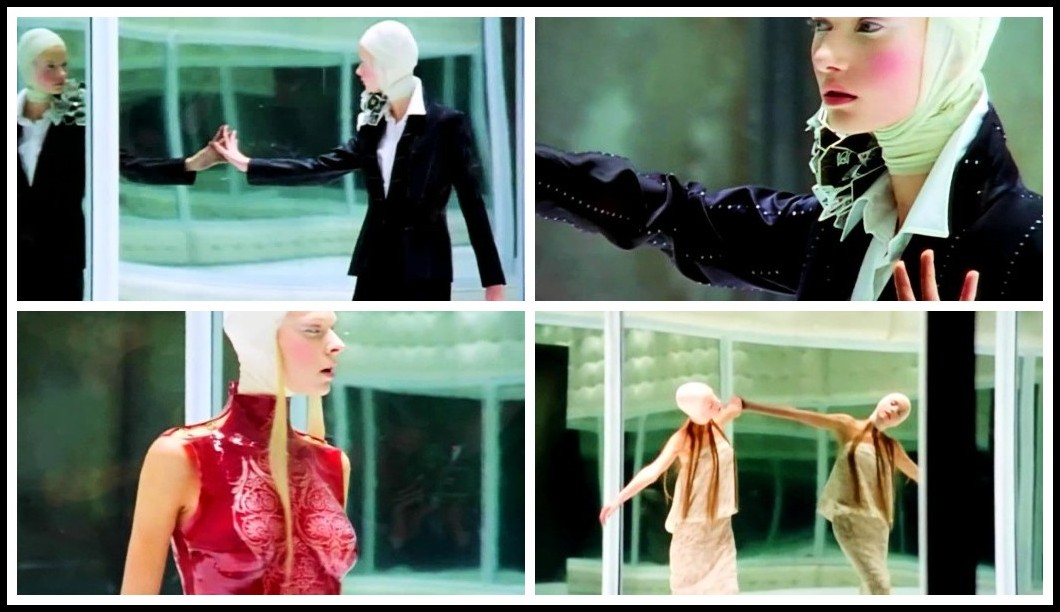

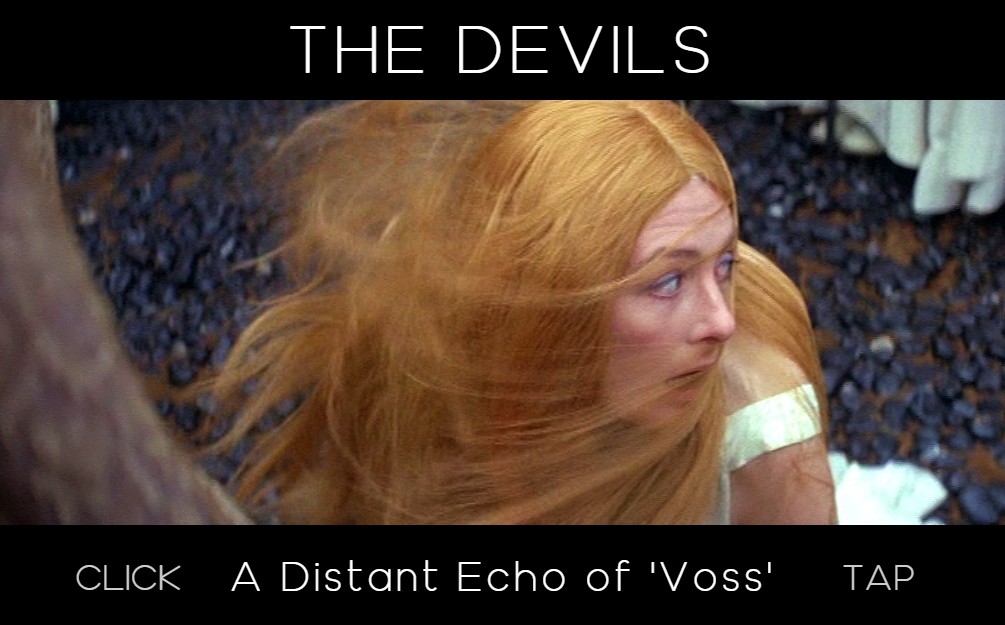

The serpents morph into a filigree of electric blue arabesques, and then the spotlights pick out two robotic arms on parallel rails, a camera where their hand should be. On the screen we see the audience they survey, a typical McQueen touch in which the unfettered gaze, through a mirror effect (as in VOSS, S/S 2001), becomes uncomfortably fettered to itself. Call this a feminist gesture, a sabotaging of the objectifying male gaze.

Alexander McQueen, Plato’s Atlantis, S/S 2010

And then they come, McQueen’s creatures, in stunning ‘armadillo’ boots and breath-taking prints, their sculpted hair evoking dorsal fins. What are they? The fruit of some ancient Greek coupling of animal and human? Of the mating of man and machine? Or simply mutants emerging post-apocalypse?

Alexander McQueen, Plato’s Atlantis, S/S 2010 | Vogue

Over the course of their fifteen-minute parade we decipher a pattern of reverse evolution: humans returning, via an amphibious state, from land to sea. And thus into fashion’s eternal now McQueen introduces time, a time that traces a possible future and gives us a space to reflect. Yes, McQueen’s aliens humanize us: one more paradox, one more feminine refusal to freeze fluidity. Note that this ‘refusal to freeze fluidity’ is inherent in female sexuality itself, and indeed in the very notion of the feminine. Indeed, as Kaja Silverman, developing Flügel’s insights, puts it:

Female dress has undergone frequent and often dramatic changes, accentuating the breasts at one moment, the waist at another, and the legs at another. These abrupt libidinal displacements, which constantly shift the center of erotic gravity, make the female body far less stable and localized than its male counterpart. I would argue that fashion creates the free-floating quality of female sexuality. The endless transformations within female clothing construct female sexuality and subjectivity in ways that are at least potentially disruptive, both of gender and of the symbolic order, which is predicated upon continuity and coherence. However, by freezing the male body into phallic rigidity, the uniform of orthodox male dress makes it a rock against which the waves of female fashion crash in vain.*

* Kaja Silverman, ‘Fragments of a Fashionable Discourse’ (1986) in Shari Benstock & Susanne Ferris, ed., On Fashion (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1994), 191-92

Alexander McQueen, Plato’s Atlantis, S/S 2010 | Vogue

Freud, in his 1909 lecture ‘On the Genesis of Fetishism’ to the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society, stated: ‘In the world of everyday experience, we can observe that half of humanity must be classed among the clothes fetishists. All women, that is, are clothes fetishists.’* Ellen McCallum, in the course of her brilliantly argued interpretation of Freud’s statement, writes: ‘Clothes fetishism emerges as desire tries to negotiate contradictions in knowledge, not only between private significances and public systems of meaning, but between private aspirations and public expectations.* Fashion, I would argue, takes place precisely in this ‘in-between’ zone, this zone where women often find themselves. This also happens to be the zone where Alexander McQueen’ artistry, particularly in Plato’s Atlantis, finds its fullest expression.

* E.L. McCallum, Object Lessons : How to Do Things with Fetishism (State University of New York Press, 1999), 51, 54

Alexander McQueen, Plato’s Atlantis, S/S 2010 | Vogue

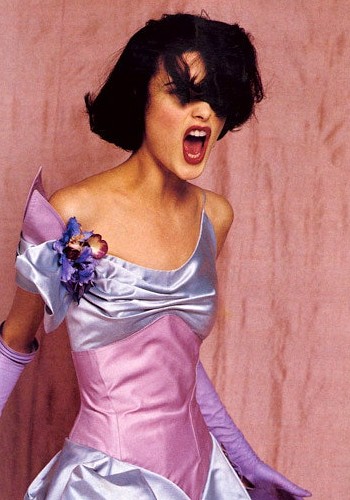

‘Fetishism offers reassurance to oneself, whereas masquerade offers reassurance to another’, writes Ellen McCallum.* McQueen leaves masquerade, the notion of femininity as nothing more than ‘seductive packaging’, to, for example, John Galliano.** Instead, he intuitively understands that ‘fetishes operate as a fundamental tool for subjects to interpret themselves and their world’.* Insofar, then, as Plato’s Atlantis plays on the notion of women as ‘clothes fetishists’ (Freud as interpreted by Ellen McCallum), we see that what McQueen is doing is empowering women by affirming the feminine. Indeed, by rejecting masquerade, which aims to ‘reassure men that nothing / no-one is really out of place’* and opting instead to assert, via the theme of a regression to the water-world, that something / someone is indeed ‘out of place’, he validates women’s refusal to be confined to the masquerade.

* E.L. McCallum, Object Lessons: How to Do Things with Fetishism (State University of New York Press, 1999), 62

** Alison Bancroft, adopting a Lacanian perspective, makes this point forcefully: ‘Perpetuating woman as objet a, as Galliano does, is repression of the most tedious and ubiquitous kind. McQueen is of a very different order, and contrarily, by using couture to represent the structural impossibility of the feminine in the symbolic, McQueen is embodying in his work the theoretical point that the jouissance of the other is where ‘otherness’ in sexuality utters its most forceful complaint.’ (Alison Bancroft, Fashion and Psychoanalysis, I.B. Tauris 2012, p. 99)

Alexander McQueen, Plato’s Atlantis, S/S 2010 | Vogue

John Galliano reassures men by displaying the feminine as a ‘veiled nothing’ : ‘When a man looks at a woman wearing one of my dresses, I would like him basically to be saying to himself, I have to fuck her’.* In contrast, Alexander McQueen, by ‘facilitating a display of the feminine as something other than a veiled nothing, provides a site of resistance in which the disruptive potential of feminine jouissance can make its appearance. What he does—which is what makes him such a radical creative figure—is offer feminine resistance to such structuring. He renders possible that which is usually impossible: a presentation of feminine resistance in the symbolic.’** McQueen’s woman is not an inflatable Galliano doll, but a living, breathing creature endowed with subjectivity and agency.

* John Galliano, 2003 interview. Quoted in Valerie Cumming, Understanding Fashion History (UK: Costume and Fashion Press, 2004)

** Alison Bancroft, Fashion and Psychoanalysis (I.B. Tauris 2012) p. 99

Kate Moss & Alexander McQueen | Mark Harrison, 2004

‘He gave women power, while letting them be fragile and vulnerable at the same time. People used to say he was a misogynist, but it took me a while to realise that he was actually empowering women.’ Kate Moss, Harper’s Bazaar, May 2011

‘Fashionable’ and ‘visionary’ are, on the face of it, antithetical terms. Yet ‘fashionable’, as defined by Adam Phillips in The Concise Dictionary of Dress*, can indeed be applied to McQueen. Zooming out from our focus on ‘feminine, femininity, feminist’, and in the belief that it will facilitate further exploration, I close this section with Adam Phillips’ definition of ‘fashionable’: 1. A form of alarm; armour for the anticipated emergency; secret knowledge of contemporary intimidations. 2. Excited impatience with the body; something made to disappear; anything that can be refashioned. 3. Of its time by promising a more alluring future; a kick start, a longing, a private nostalgia. 4. History without footnotes; in the past in new clothes; undercover conservation. 5. Taking liberties on the future and parasitic on it. 6. Anything that tries to stop the present collapsing back into the past; the new without fear. 7. Something that makes space for itself. 8. An experiment with pleasure, without proof; living for the last moment.*

* Judith Clark & Adam Phillips, The Concise Dictionary of Dress (London: Violette Editions; 2010), 58

Alexander McQueen, Plato’s Atlantis, S/S 2010

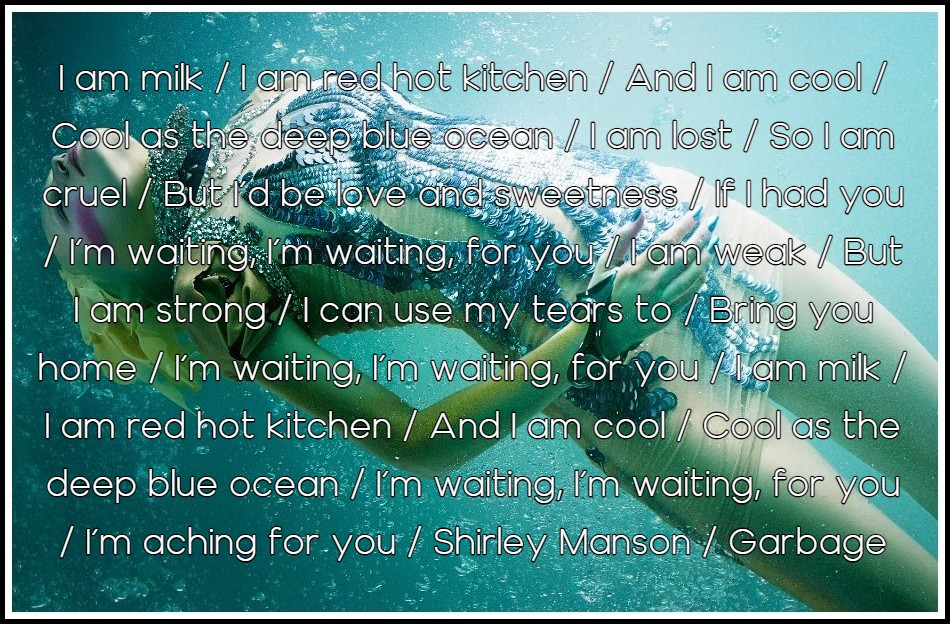

What does Alla Kostromicheva in Sølve Sundsbø’s ‘The Girl from Atlantis’ evoke in you? For me, she evokes ‘Milk’, the Garbage song sung, of course, by Shirley Manson. (You can find the song and an analysis of it by clicking on the second link in the image caption.)

Sølve Sundsbø, ‘The Girl from Atlantis’, Vogue Nippon May 2010 | ‘Milk’, Shirley Manson – Garbage

ALEXANDER McQUEEN—PLATO’S ATLANTIS—COMPLETE SHOW

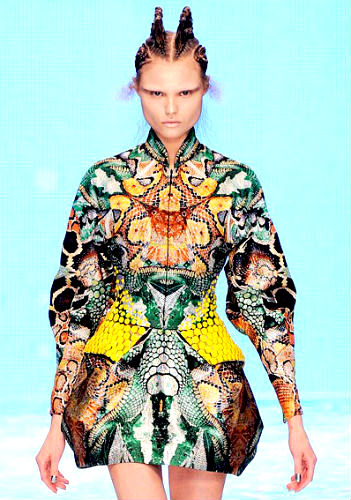

III. ALEXANDER McQUEEN: THE GIRL WHO LIVED IN THE TREE | F/W 2008

Palais Omnisports de Paris-Bercy, Paris | 29 February 2008

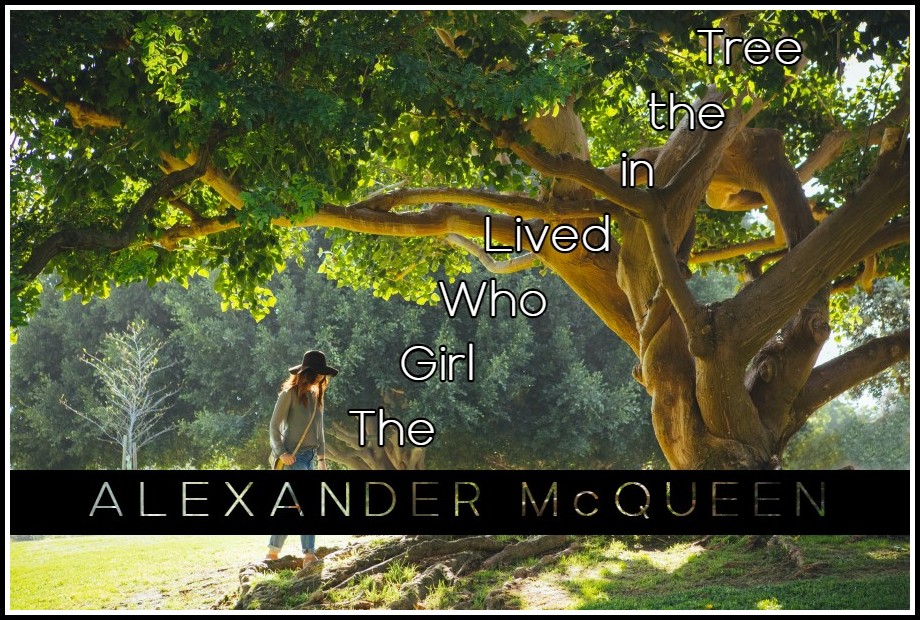

Alexander McQueen, The Girl Who Lived in the Tree, F/W 2008-09 | Photo: Kevin Young | Text layout: RJ

Once upon a time, in the village of Fairlight, on the grounds of his cottage overlooking the sea, Alexander McQueen contemplated a tree. Six-hundred years old it was, a real immemorial elm. Suddenly a vision occurred to him: A girl, a wild creature, lives up there, sheltered in the darkness. Letting his imagination run, he saw her descending; as soon as she touched the ground, she was transformed into a princess.

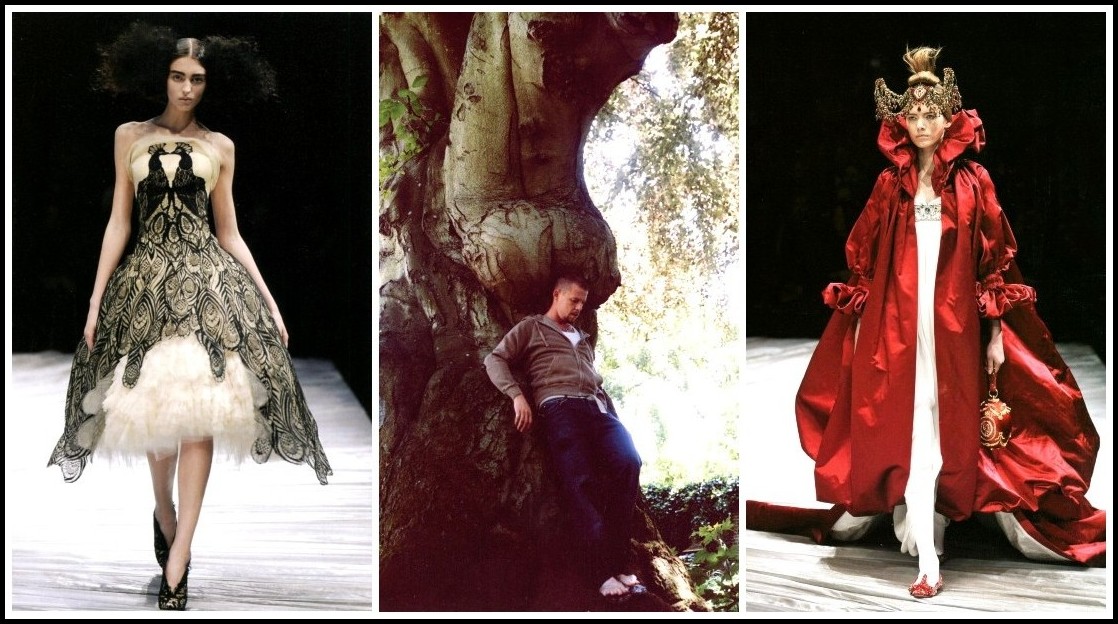

Alexander McQueen, The Girl Who Lived in the Tree, F/W 2008-09 | McQueen photo: Sam Taylor-Johnson

And thus it was that a weekend away from the hurly-burly of London allowed McQueen to produce a collection that celebrated light, a collection in which he no longer showed any need to slash the vestments of would-be princesses. Like any genuine artist, however, he could not help but be true to himself: The first half of The Girl Who Lived in the Tree was governed by the colours of night, but a night in whose womb day was already gestating.

Alexander McQueen, The Girl Who Lived in the Tree, F/W 2008-09

My breath was taken away by the beauty of his night creations, whether in the glossy black that mirrors shining white or in the dusky tones of a world shielded from sunlight: the abode of the girl in the tree. Indeed, I much prefer the feral to the regal—but that’s beside the point: What I want to show here is how McQueen, via this utterly simple story of darkness to light, wild child to princess, remains true to his vision of celebrating women from a feminist perspective.

Alexander McQueen, The Girl Who Lived in the Tree, F/W 2008-09 | Campaign photo: Craig McDean

Hark! I hear from across the Atlantic (I write this from France) the cries of outraged feminists. Is not the princess, they rhetorically ask, the central figure in the script of femininity that subjugates women to patriarchy? Is not the princess the vehicle by which girls learn it’s better to be passive and patient than to act and venture forth? Yes, yes, I say. They calm down. And then I say: There are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy. Now they refuse to give me a hearing. No matter. This is what I have to say. Listen.

Alexander McQueen, The Girl Who Lived in the Tree, F/W 2008-09 | Gayatri Malhotra, Unsplash

McQueen begins with the wild child, the girl who lives in a tree. Now why do girls become wild, why do they go and live in a tree? For the same reason that the nymph Daphne turns herself into a laurel tree: to escape a man’s (in this case, a god’s, Apollo’s) advances. Indeed, every nubile girl is beautiful, and beauty is a synonym of desire: And herein lies the source of all the girl’s troubles. Sexuality threatens to overwhelm her. Vaguely she senses that husband, house and baby are but a conspiracy to tame her ‘animal instincts’, and yet that trinity is attractive because, were ‘everything in order’ (socially), her emotional turbulence would surely subside. Vaguely she may be aware that it’s better to do than to merely be (beautiful), and yet, since the dress makes the princess, why not go the easy route?

Alexander McQueen, The Girl Who Lived in the Tree, F/W 2008-09 | Maria Lysenko, Unsplash

Ambivalence and ambiguity characterize the nubile girl, and this is reflected in McQueen’s story. By living in a tree, the girl renounces the social effects of her beauty; she cultivates her affinity with the non-human—the animal, the vegetal—and may deliberately dirty herself, make herself ugly. McQueen makes the point with subtle economy: The hairstyle of the ‘girl in darkness’ suffices to convey it. The girl in the tree, then, the little savage who prefers the woods, is simply the negative image of the figure of the princess: as night to day, as black to white, as darkness to light.

Alexander McQueen, The Girl Who Lived in the Tree, F/W 2008-09 | James Armes, Sleep Music, Michael Larosa – Unsplash

Once again, then, McQueen proves himself finely attuned to the potentialities of the feminine, and more broadly, to the dynamics of desire. In this, he is a feminist, affirming women.

Alexander McQueen, The Girl Who Lived in the Tree, F/W 2008-09

ALEXANDER McQUEEN—THE GIRL WHO LIVED IN THE TREE—COMPLETE SHOW

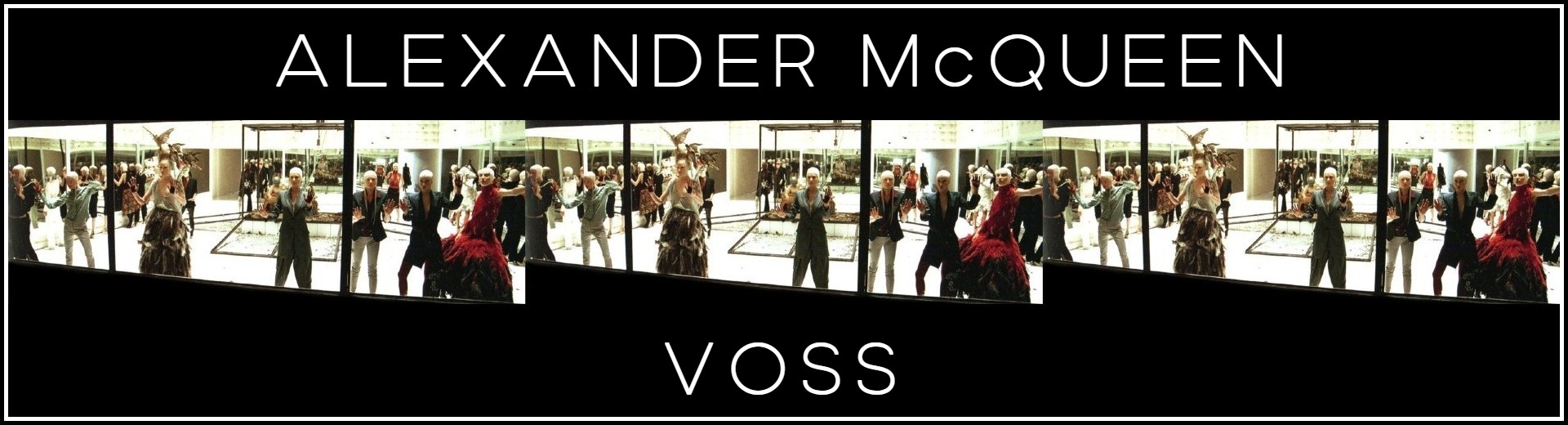

IV. ALEXANDER McQUEEN: VOSS | S/S 2001

Gatliff Road Warehouse, London; 26 September 2000

Alexander McQueen, Voss, S/S 2001

The asylum, as an institution, offers a fecund point of intersection for our trilogy of feminine, femininity and feminist. As Lisa Appignanesi points out in her book Mad, Bad and Sad: A History of Women and the Mind Doctors from 1800 to the Present, ‘frenzies, possessions, manias, melancholy, nerves, delusions, aberrant acts, traumatic tics, passionate loves and hates, sex, visual and auditory hallucinations, fears, phobias, fantasies, disturbances of sleep, dissociations, communication with spirits and imaginary friends, addictions, self-harm, self-starvation, depression—there are so many riveting cases of women, and through them a large part of what we recognize as the psychology professions was constructed’. Indeed, growing up female in just about any society complexifies the already complicated dynamics of becoming an individual (oneself) and a free and responsible person (one’s social being). Here, girls and women have it harder, and, in a world governed by men, it is not surprising to find them all too often in asylums.

* Lisa Appignanesi, Mad, Bad and Sad: A History of Women and the Mind Doctors from 1800 to the Present (UK: Virago Press, 2008) 1, 6

Alexander McQueen, Voss, S/S 2001

McQueen, as everyone familiar with his biography knows, suffered two foundational traumas in his childhood. One was witnessing, repeatedly and helplessly, his sister Janet, 15 years his senior, getting beaten and ‘almost strangled to death’* by her abusive husband. The second, unbeknown to Janet, was getting raped, from the age on nine on, by that same man.** McQueen transmuted these traumas to varying extents all across his career. In Voss, what resonates with me in this regard is the notion of incommunicable experience…

* Dana Thomas, Gods and Kings: The Rise and Fall of Alexander McQueen and John Galliano (Penguin Press, 2015) 67

** Vogue, 18 May 2015

Alexander McQueen, Voss, S/S 2001

… of eloquent silence…

Alexander McQueen, Voss, S/S 2001

… of looking out from within, radically isolated, unable to connect with anyone.

Alexander McQueen, Voss, S/S 2001

What might a reading of Voss that juxtaposes the silence cloaking violence and rape (McQueen’s childhood traumas) with the ‘bandaged’ heads suggesting ECT and lobotomy (the ‘madness’ of the models) make of the sanctum in the asylum, the cube within the cube? Might not that metal-mirror box contain an elephant in the room?

Alexander McQueen, Voss, S/S 2001

Indeed, it does: The box discloses a moth-infested masked odalisque (a tableau vivant of Joel Peter Witkin’s photograph ‘Sanitarium’), an elephant in the room standing for a time when time stood still: a summons from beyond the grave, a trauma come alive, a creature excavated from the crypt of oneself.

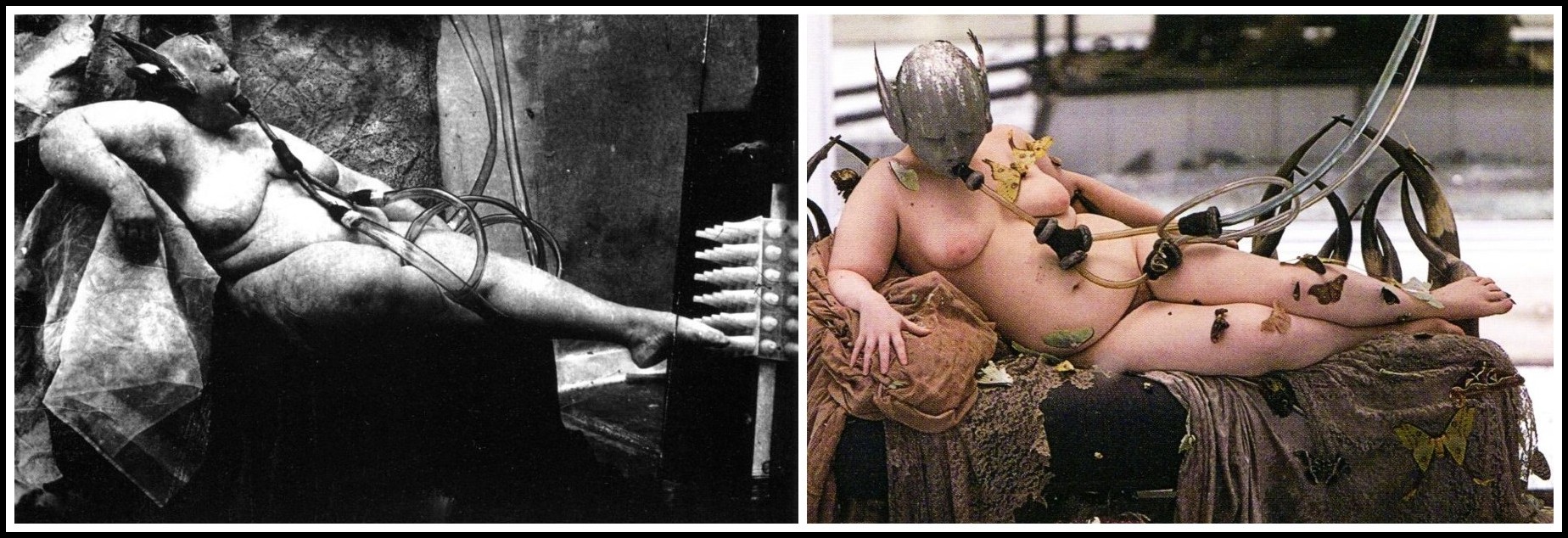

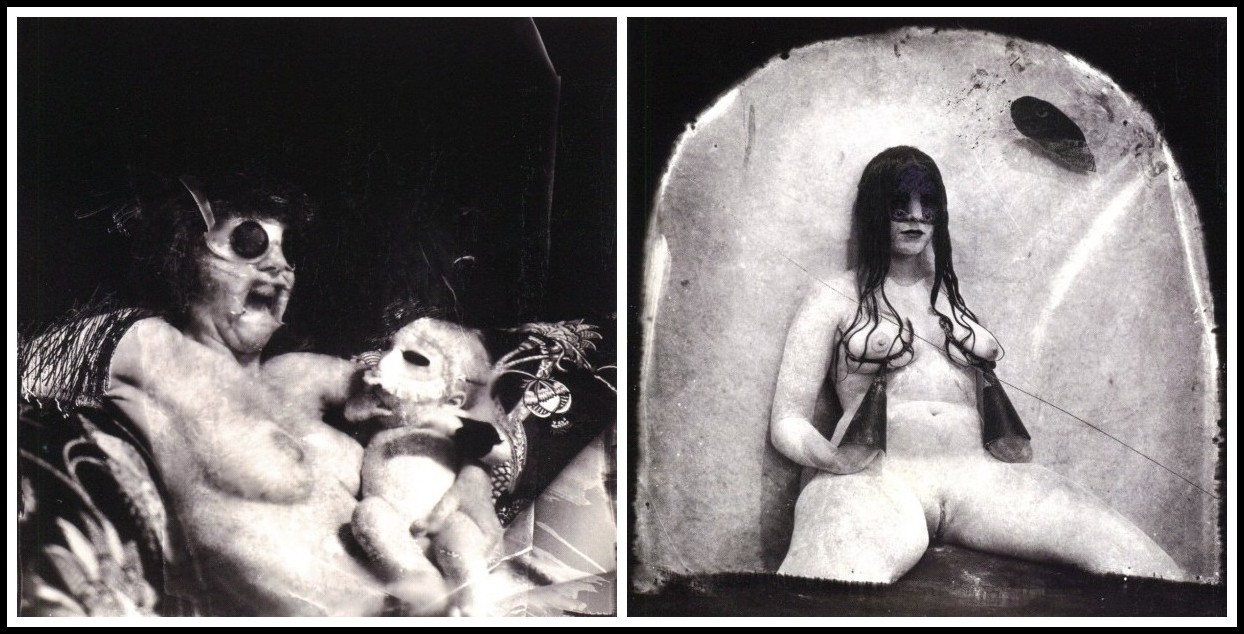

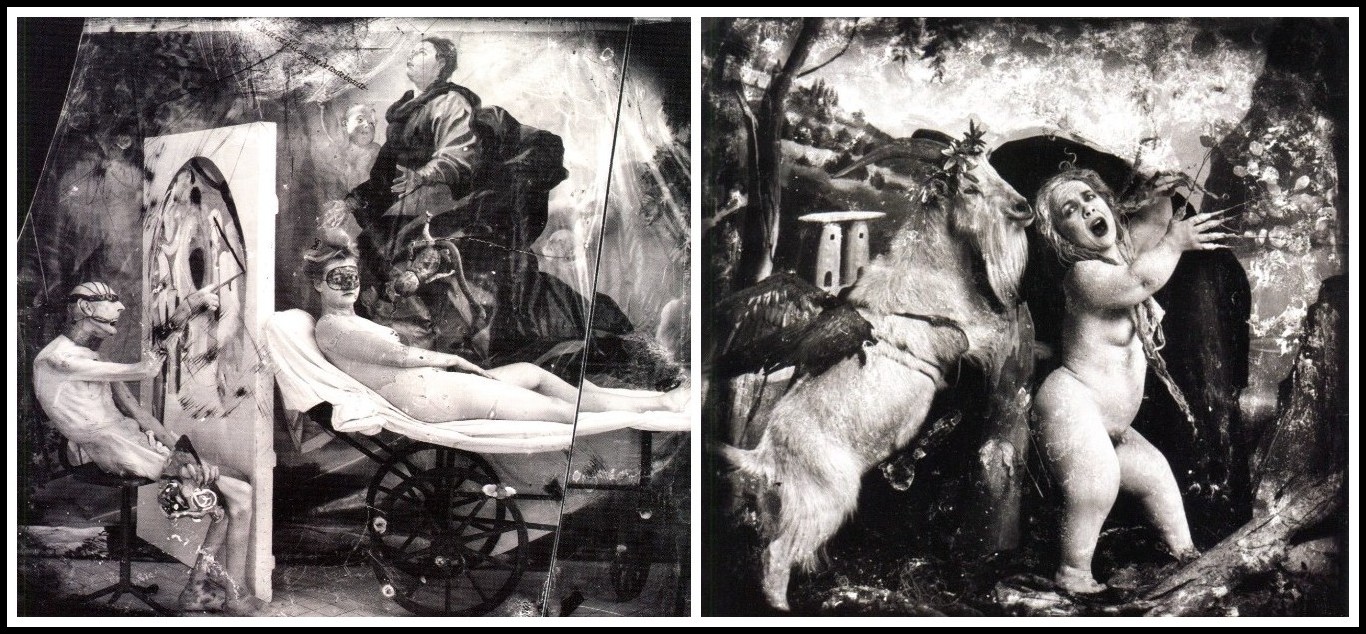

Joel-Peter-Witkin, Sanitarium, 1983 | Alexander McQueen, Voss, S/S 2001

Has McQueen, in Voss, unsealed his lips? Is he, unbeknownst to himself, making his silence eloquent, speaking of that whereof he cannot speak?

Alexander McQueen, Voss, S/S 2001 | Alexander McQueen, 1992 (Simon Costin)

Has the violence inflicted on the child robbed him of his innocence?

Joel-Peter Witkin, Mother and Child, 1979 | The Bra of Joan Miró, 1982

Is the artist transmuting his traumatic experience into art?

Joel-Peter Witkin: Poussin in Hell, 1999 | Daphne and Apollo, 1990

Now what of women and madness and McQueen’s models, what of the women in the asylum? Via four authors I will present, without comment and by way of conclusion, four aspects of this reality, each one followed by images from Voss and an abandoned asylum. First, the poet Emily Dickinson.

EMILY DICKINSON

Madness

Much Madness is divinest Sense

To a discerning Eye;

Much sense the starkest Madness –

‘Tis the Majority

In this, as all, prevail.

Assent, and you are sane;

Demur, you’re straightaway dangerous

And handled with a Chain

Emily Dickinson, Fascile 29 of Emily Dickinson’s Poems as She Preserved Them, ed. Cristanne Miller (Harvard University Press, 2016) 304

Alexander McQueen, Voss, S/S 2001 | Nathan Wright, Unsplash

Next, writer and philosopher Hélène Cixous.

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS

The Hysteric

The hysteric is a divine spirit that is always at the edge, the turning point, of making. She is one who does not make herself. She does not make herself but she does make the other. It is said that the hysteric plays, makes up, makes-believe: she makes-believe she is a woman, unmakes-believe too. She’s the unorganizable feminine construct, whose power of producing the other is a power that never returns to her. She is really a wellspring nourishing the other for eternity, yet not drawing back from the other, not recognizing herself in the images the other may or may not give her. She is given images that don’t belong to her, and she forces herself, as we’ve all done, to resemble them.

Hélène Cixous, ‘Castration or Decapitation?’ tr. Annette Kuhn. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society Vol. 7, No. 1 (Autumn, 1981) 47

Alexander McQueen, Voss, S/S 2001 | Hans Eiskonen, Unsplash

Next, psychoanalyst Nitza Yarom.

NITZA YAROM

The Feminine and Recourse to the Body

From its beginning hysteria was associated with women and femininity. In the psychopathology of sexuality, we find that women tend to resort to hysteria more than men, and men tend to utilize perversion. The recourse of women to the body and of men to transgression of the law is also found in addictions. Here too, men resort more to addictions of drugs and alcohol, while women turn to anorexia and bulimia. The fact that biology forces women to deal with their bodies and the bodies of others more often than men is one conceivable reason why the body may remain a major channel for the communication of the feminine.

Nitza Yarom, Matrix of Hysteria: Psychoanalysis of the Struggle between the Sexes as Enacted in the Body (London: Routledge, 2005) 37

Alexander McQueen, Voss, S/S 2001 | Sean Robertson, Unsplash

And finally, psychoanalyst Darian Leader.

DARIAN LEADER

How is a woman looked at when she enters the phantasy space of a man?

What does it mean to be looked at? When we become the object of someone else’s gaze, aren’t we always looked at as something? Whether we like this or not, it offers us an identity: transitory, permanent, contested or agreed, it protects us from the anxiety of not knowing what place we occupy for the Other. But how far can this go? What are the limits of the image? To what extent can an image both supply and sustain our identity? As we internalise the image others have of us as our own, our image becomes in some sense the property of others, never fully belonging to us. Our ego is simultaneously our alter ego. This alienation is only reinforced in the field of love and desire. How is a woman looked at when she enters the phantasy space of a man? Beyond the more general questions of the performative nature of masculinity and femininity, to take up a place within a man’s desire entails a loss of oneself. To be desired means being desired for something beyond oneself, for some trait or detail that resonates with a man’s phantasy. In artist Dawn Woolley’s series ‘The Substitute’, men embrace cut-out images of women, apparently unaware that they are no longer with a flesh and blood person. This is a perfect definition of male desire, the object of which is ultimately mortified, through the very action of being transported into their phantasy space. The image, then, although it gives us a place, is not enough to sustain us.

Darian Leader, ‘Cut-Outs’, in Dawn Woolley, Visual Pleasure (Wales: Fotogallery, 2010) 7-10

Alexander McQueen, Voss, S/S 2001 | Patrick Pierre, Unsplash | Nathan Wright, Unsplash

ALEXANDER McQUEEN—VOSS—COMPLETE SHOW

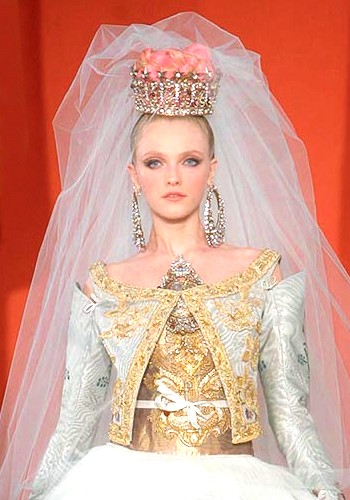

V. CODA

Alexander McQueen’s shows had a dimension ‘above and beyond’ those of his contemporaries, and indeed of prior generations of designers and couturiers. In terms of the clothes presented, Christian Lacroix was unbeatable for pure beauty; for marrying fabric to flesh and bone, Yves Saint Laurent was sans pareil; for a sense of play Jean-Paul Gaultier reigned supreme, and for luxuriant sexiness the first port of call was Azzedine Alaïa. If a given outfit of any of these artists could match a given McQueen creation along any of these parameters, in what way was McQueen ‘above and beyond’ the others? Something filmmaker Andrzej Zulawski said will enable me to provide a succinct answer. Here’s the quote: ‘When you build a house, you have the ground floor, and then you need a second floor, you need something to transpose the story, something that gives it meaning. It’s like in fairy tales where you have something ordinary and then you have a witch or a devil, something out of the ordinary. The first part of the film [Possession] establishes an ordinary situation and then it goes one level above in order to give it a mythical dimension.’ Alexander McQueen’s shows, I contend, were never content to remain on the ground floor: they always went ‘one level above’, they always integrated a ‘second floor’, a ‘witch or a devil’ to give them a ‘mythical dimension’. It is this that distinguishes McQueen from other designers, and it is this that I have tried to articulate in this post. Here I focused on ‘feminine, femininity, feminist’; in a future post I will highlight other routes McQueen took to the mythical dimension.

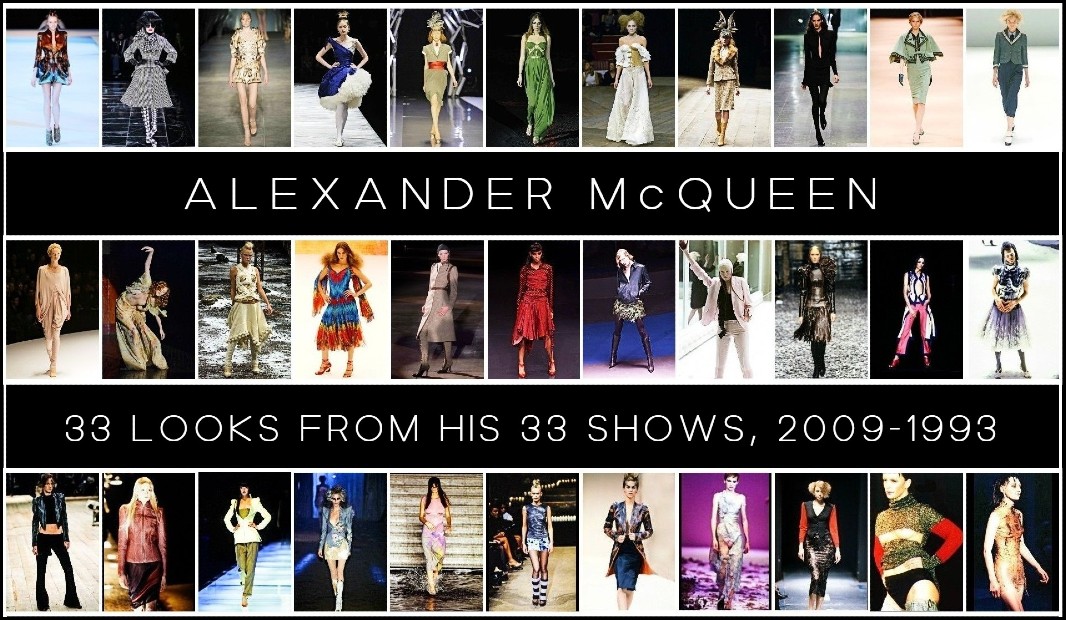

Alexander McQueen, 33 Looks from his 33 Shows, 2009-1993

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

ALEXANDER McQUEEN – CLICKABLE IMAGE LINKS: PRINT INTERVIEW | ARTICLE | VIDEO DOCUMENTARY

Alexander McQueen ‘Cutting Up Rough’

‘The Works’ (BBC documentary), 1997

FASHION IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

CLICK ON AN IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2022 | All rights reserved

Comments

2 thoughts on “Alexander McQueen: Feminine, Femininity, Feminist”

Thanks to this post, I discovered just how much Alexander McQueen is an artist and not just a designer, as so many people believe. Art seems to have inhabited this endlessly creative soul as he designed clothes. This was all the more surprising to me as Alexander McQueen’s own way of dressing is so far from typical Parisian style. The contrast between his apparent simplicity and the sophistication of his conception of femininity really struck me. Brilliant!

I love the shimmering beauty of the photos and video (Plato’s Atlantis)! A very good choice, since the article is particularly illuminating about both the nature of the masquerade Alexander McQueen relishes and, more broadly, the elusiveness of the feminine. Difficult animals to pin down, these figures of Atlantis!