CHRISTIAN LACROIX ON CHRISTIAN LACROIX: THE MAKING OF AN HAUTE COUTURE DESIGNER

PART ONE OF THREE

From Christian Lacroix, ‘Pieces of a Pattern: Lacroix by Lacroix’, Chapter 8: Couture!

Christian Lacroix, Pieces of a Pattern: Lacroix by Lacroix. Edited & introduced by Patrick Mauriès, translated by Barbara Mellor (Thames & Hudson, 1992) pp. 145-184

Christian Lacroix, 2002 | Photo: François Halard, Vogue

Oddly enough, though my livelihood depends on changing tastes, I have never felt any need to disown passing fashions or condemn them as outmoded, or to dismiss once-cherished clothes as ‘frightful’ or ‘unwearable’. I tend not to pigeonhole things, perhaps especially because I have always had an almost morbid fascination for the past—which starts with every passing moment—to the extent that for me everything is imbued with an almost unhealthy degree of nostalgia. I am like the English, who, as a friend of mine used to say, have ‘a sense of period’.

THE ENGLISH: ‘A SENSE OF PERIOD’: EVENING DRESSES (I)

Unknown designer, 1877 | John Redfern, 1909 | Edward Molyneux, 1935 | © V&A Museum, London

THE ENGLISH: ‘A SENSE OF PERIOD’: EVENING DRESSES (II)

Owen Hyde Clark, 1955 | Thea Porter, 1970 | Hardy Amies, Cocktail Dress, 1960 | © V&A Museum, London

For me every era has something of interest to offer, if not in its reigning fashions or general trends then in some detail or other, or a way of wearing long-forgotten clothes or of putting together accessories that have long since been consigned to oblivion.

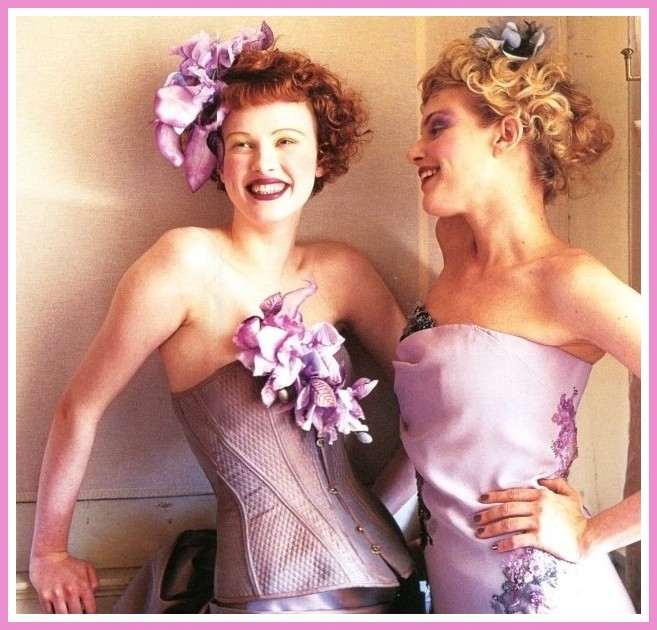

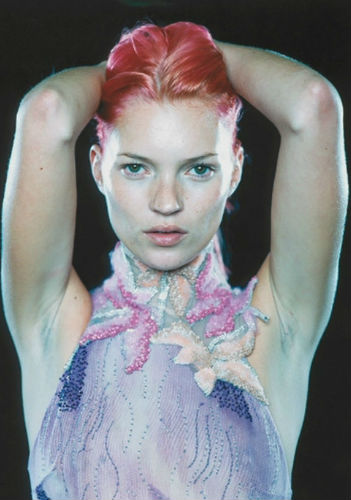

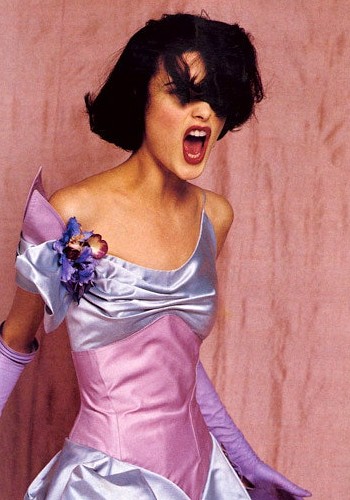

CHRISTIAN LACROIX | VOGUE

‘Lacroix’s ultra-sensitive palette in lilac, rosewood and copper:

boned corset, silk bustier and a splash of white silk pansies.’

(Linda Watson, Vogue Fashion, 2008) p. 280

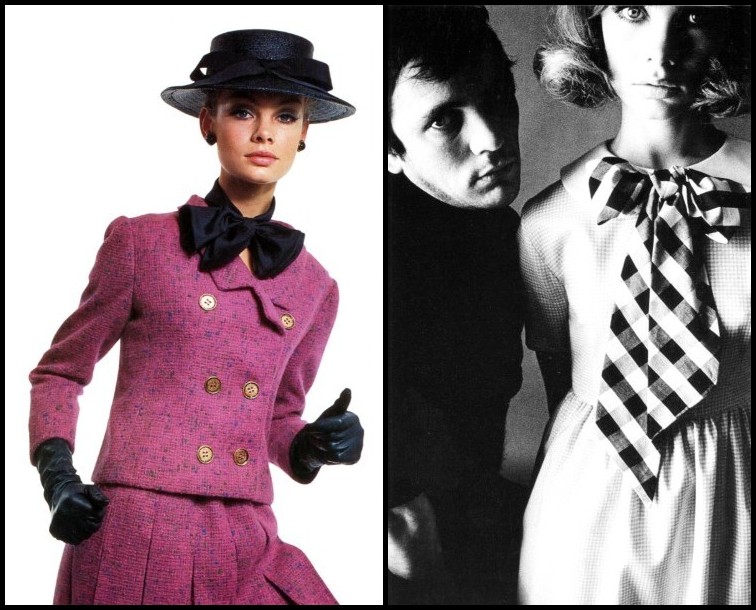

There is only one time for which I have never felt any great warmth, and that is the years 1975 and 1976, when the virtual dictatorship of ready-to-wear ended up, predictably, by producing a sort of levelling down, with the same ‘designer clothes’ and ready-made outfits available more or less everywhere. That was the point when I felt that on the whole I’d rather go back to the flea markets. The clothes of the years immediately before this (1965-70), on the other hand, have always remained very close, even indispensable, to me, possibly because these were the fashions of my adolescence, when I started to choose my own clothes and build up my wardrobe. But I also believe very strongly that for the past twenty years we have been engaged in attempts to extract and explore different aspects of the fashions of that time, with all their radical innovations.

JEAN SHRIMPTON, YVES SAINT LAURENT, 1964 | TERENCE STAMP & JEAN SHRIMPTON, 1963

Photos: David Bailey, Vogue

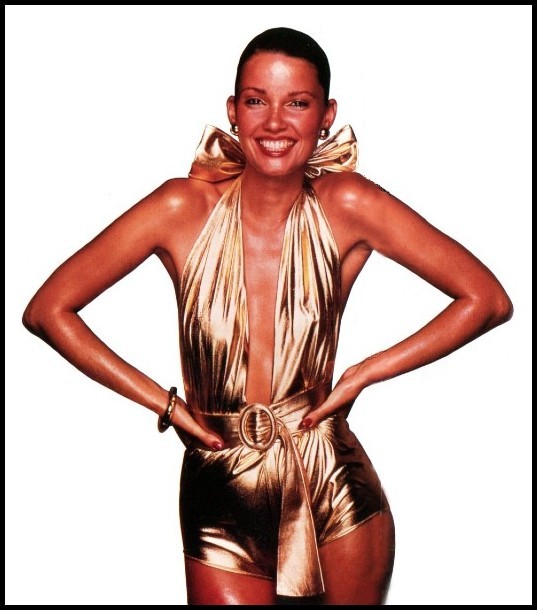

The seventies–considered as a style–were the age of the discovery of kitsch and all that was ‘cheap’. The materials that were used, in the form in which they reached the streets at any rate, speak for themselves: imitation leather, skinny rib-knit sweaters, plastic, vinyl with the transparent film inevitably peeling off, heavy fake-metal buckles and so on, all in aid of a style based pretty closely on that of the 1930s. I absolutely do not believe in the notion of ‘re-creating’ a particular style or look. (Marguerite Carré, one of Dior’s principal collaborators in the New Look era, once told me that she had refused to become involved in the reconstruction of one of the styles for a museum because she believed the whole enterprise to be simply impossible, as so many essential though apparently trivial ingredients–textures, body proportions, the model’s hands and her imagination, all inextricably linked, had changed: models embody the spirit of the times.)

1970s silky jersey playsuit | Vogue

It was also during the seventies that the element of dandyism disappeared from the world of fashion, along with the overriding desire for originality, the taste for aesthetically pleasing details, for far-fetched names and explosive combinations, and the sheer daring that people needed in order to assert their own tastes and impose their own choices, still very much a feature of the sixties.

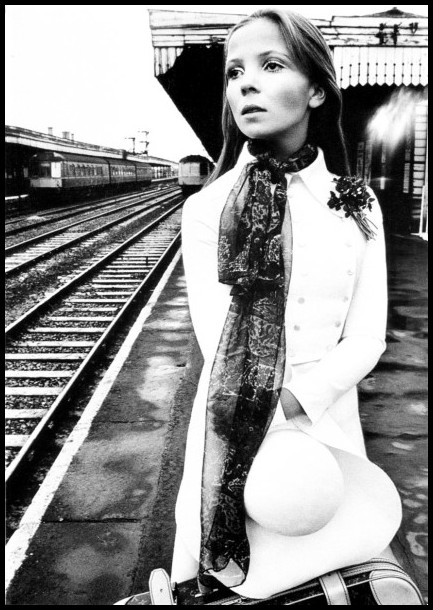

OSSIE CLARK, 1968

Photo: David Bailey, Vogue | Model: Penelope Tree

The work of a designer like Claire McCardell in America in the 1940s, for example, at once elegant and practical, seems to me to be the embodiment of the true spirit of modernity. It also proposes a model from which many lessons remain to be drawn, displaying the same spirit which inspired the distilled furniture designs of Knoll—and which was quite different from the natty trendiness of the sixties in France. Were I to be asked today to name my main pole of attraction, to which I keep returning and in which I never cease to discover fresh complexities, clearly it would be the sixties, just as I was fascinated as a teenager by the Second Empire and the 1940s.

CLAIRE McCARDELL, DRESS, UNDATED | CLARIE McCARDELL, PLAYSUIT, 1953

Photos: Maryland Historical Society | John Rawlings, Vogue

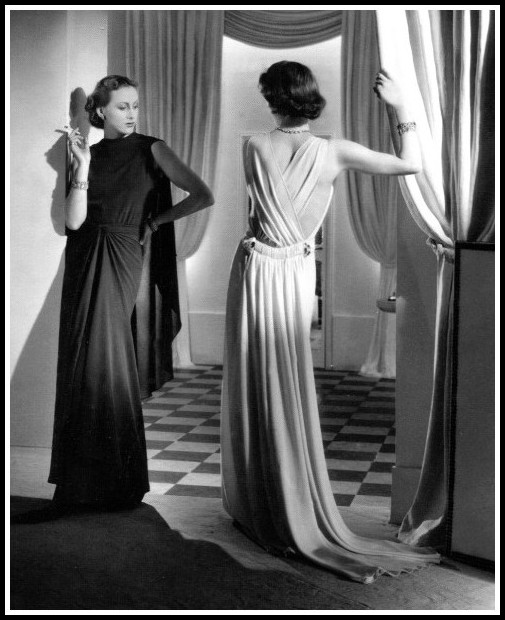

For twenty years of my life the fashions of Paris under the Occupation exercised an almost hypnotic power over me: fragile constructions of feathers and draped jersey, mixtures of sulphur yellow and wine red, a clandestine elegance.

LUCIEN LELONG, EVENING GOWNS, 1935

Photo: Horst P. Horst

And the years following the New Look represent for me in every field the apex of a certain ‘Parisian civilization’. You can of course be Parisian without having been born in Paris—sometimes it’s even an advantage. Cristobal Balenciaga is the finest example of Italian sensuality and British chic, combined with the natural grandeur of Spain. This cocktail could perhaps only have been created in Paris, and maybe the recipe is now lost. But I hope not.

CRISTOBAL BALENCIAGA, EVENING DRESS, 1952

Photo: Henry Clarke, Vogue

People often refer to the ‘sixth sense’ of fashion designers, to their ability to anticipate new directions in taste and define them before anybody else; and indeed I believe that if anything can justify the esteem in which they are held it is this.

JEANNE PAQUIN, 1928

‘Jeanne Paquin often had ideas that were ahead of the times.

She dared to combine fur with the airiness of chiffon,

pastel colours with a touch of vivid red (le rouge Paquin),

which she also liked to contrast in unexpected ways with black.

In that, she’s a precursor of Christian Lacroix.’

Bertrand Meyer-Stabley, Douze couturières qui ont changé l’Histoire

(Paris: Pygmalion-Flammarion, 2013) pages 58 & 55.

Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

But it is not enough to be able to foresee these things: you also have to be able to choose the right moment at which to do so, not too early and not too late. While some designers seem to excel at this game of judging precisely the right moment, knowing exactly how best to match changes in taste with public expectations, I have a tendency to be always slightly out of step, which ultimately has the effect of ruling out certain choices for me.

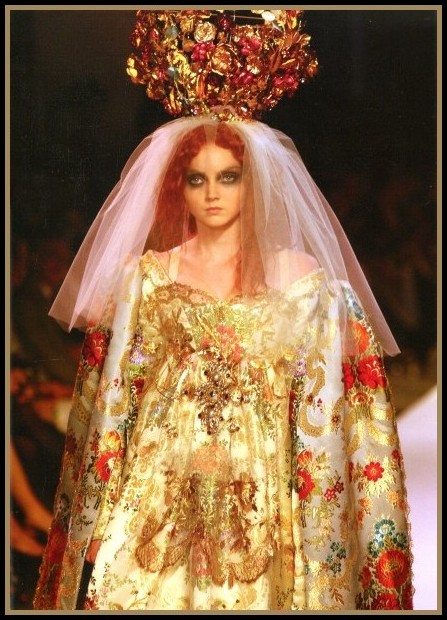

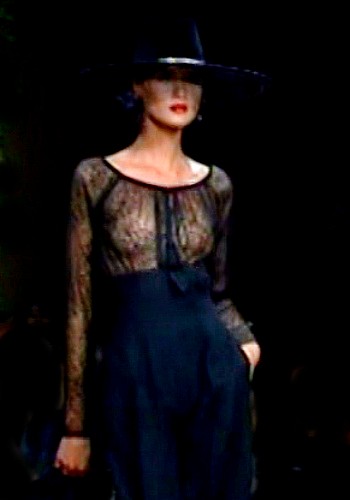

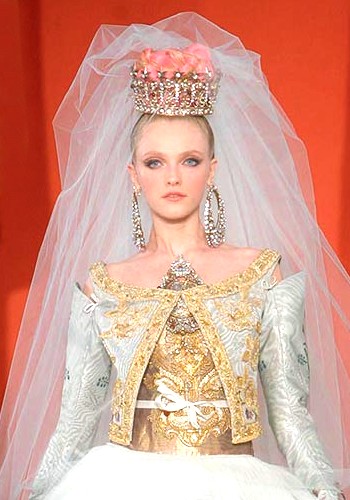

CHRISTIAN LACROIX, COUTURE, FALL 2007

Photo: Antoine de Parseval | Model: Lily Cole

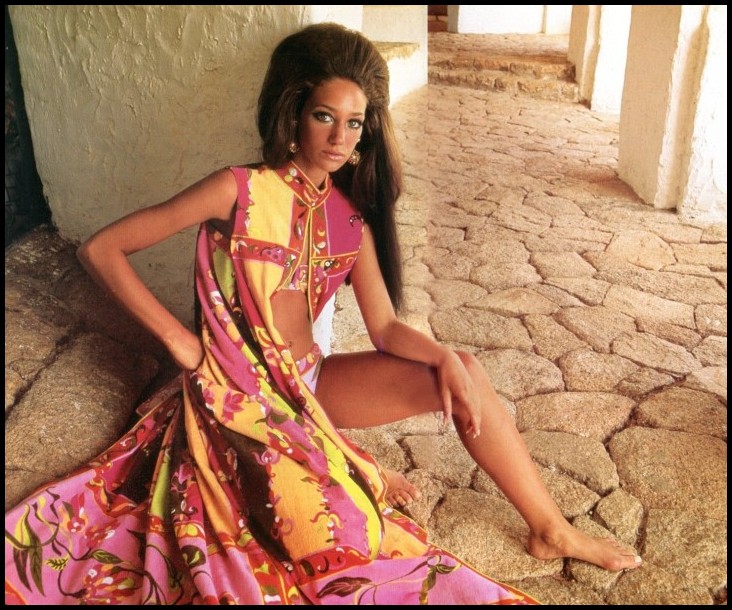

When I was still at Patou, for instance, I asked the fabric manufacturer Ratti to produce some prints for me in the Pucci style, with those great swirls of vivid colour in dazzling contrasts, on jerseys or other clinging materials. Absolutely the height of ‘Italian chic’ in the sixties, they were equally absolutely out of fashion twenty years later; and when Pucci did finally come back into vogue, in 1990-91, I was already bored with them and in any case had no further use for them.

EMILIO PUCCI, STRETCH BIKINI & VELVET ROBE, 1968

Photo: Henry Clarke, Vogue | Model: Marisa Berenson

It was the same, to a lesser degree, with the style of the thirties, with which I used to fill my school notebooks. The whole area is one in which personal judgment and the subtlest of gauges are the only arbiters, where processes that are beyond the reach of intellect are at work, which ultimately we can only observe in ourselves as they take shape. It is in this mysterious process that all the excitement of the business lies; it was also at the moment when I realized that I possessed this gift, quite unconsciously and wholly outside my control, and that it might be able to earn me a living, that I really made my entrance into the world of fashion.

Marlene Dietrich, Portrait for Shanghai Express, 1932 | Greta Garbo, Portrait for Anna Karenina, 1935

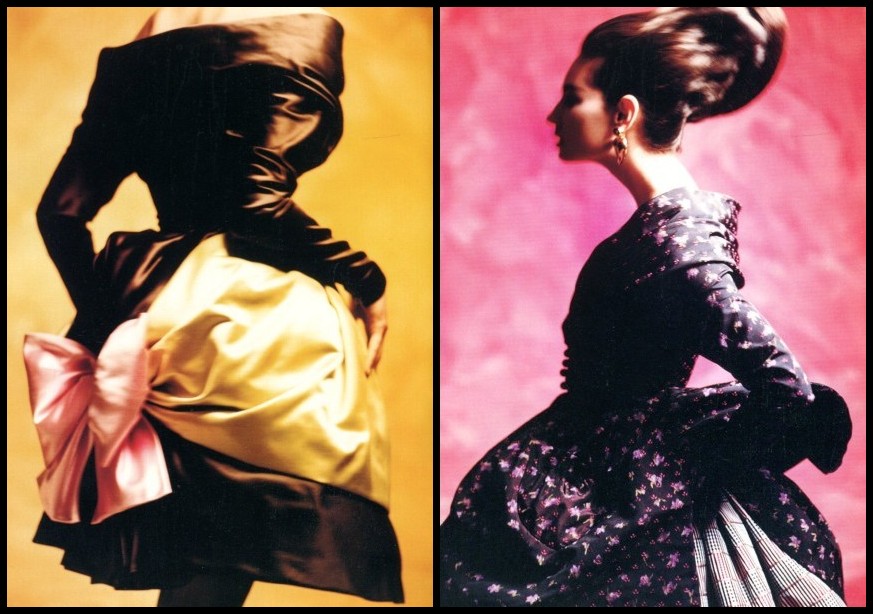

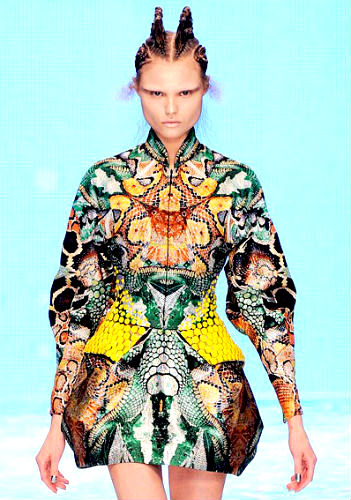

In choosing our moment to launch the fashion house, in contrast—at least to judge by the welcome we received—there can be no doubt that our timing was just right; we seemed to have uncovered a latent desire for a return to the luxury, playfulness and excesses of haute couture.

Christian Lacroix, 1987 | Photo: Patrick Demarchelier, Vogue

But of course every rose has its thorns, and we soon had to take in hand the heavy, monolithic image we became saddled with, which was both distorted and distorting. Although it gave us an identity, it also imposed its own limitations. Now I see my work as consisting of putting myself in a particular setting and changing it little by little, of directing my clients’ tastes towards new possibilities.

Christian Lacroix, Couture, 1987 | Photos: Javier Valhonrat

Gone are the arbitrary, undirected enthusiasms of the early years, the innovations for their own sake, the wild and unrestrained experimentation.

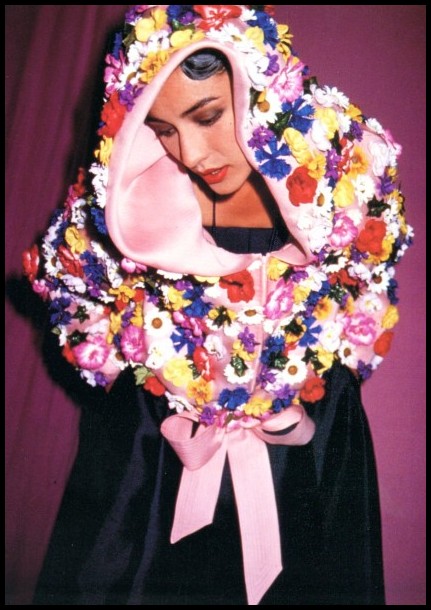

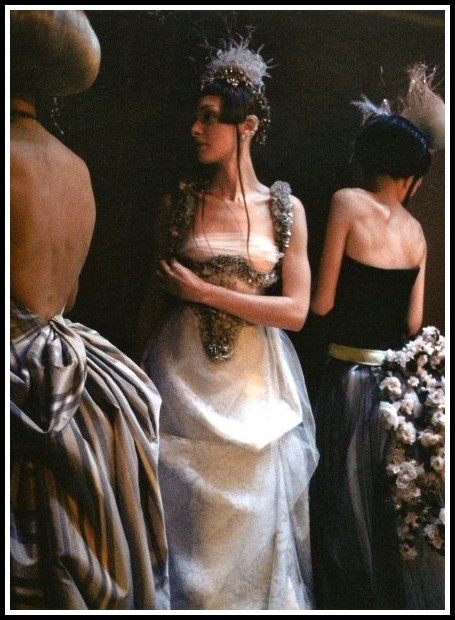

CHRISTIAN LACROIX, COUTURE, SS 1989

Photo: Roxanne Lowit

I have learned to control certain flights of fancy, when they are in danger of bringing me too close to some fashion or other, and I would like to curb still further the tendency towards a sort of ‘fashion culture’, even though I am still avid to know every detail of all the press shows and would go to every single one if I could, and read all the reviews and more. But at the same time I must confess that I do rather regret the increasingly dictatorial tone adopted by the fashion press, which is tending to usurp the designer’s role in developing and formulating new ideas. In a field where the freedom to create is already limited by pressure from buyers to repeat lines that sold well last season, this merely imposes one more limitation.

DAVID BOWIE’S ‘FASHION’ (1980) ECHOES CHRISTIAN LACROIX’S ‘THE INCREASINGLY DICTATORIAL TONE ADOPTED BY THE FASHION PRESS’

There’s a brand new talk, but it’s not very clear

That people from good homes are talking this year

Oooh bop, FASHION!

It’s loud and it’s tasteless, I’ve not heard it before

You shout it while you’re dancing on the-uh dance floor

Oooh bop, FASHION!

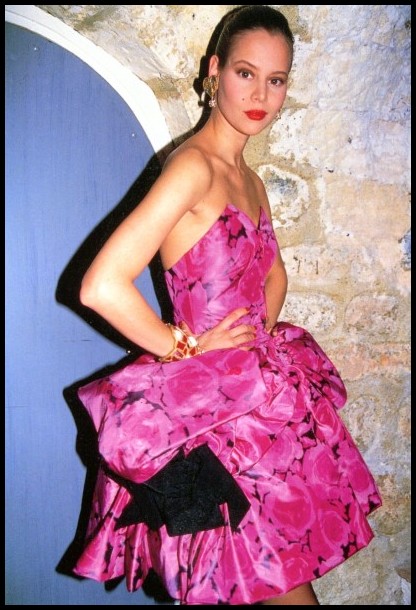

Happily the fashion house has been set up in such a way that we are not obliged to design with any particular client in mind. I still believe that the most faithful among our clientele will always find something to suit them among the designs of any given collection. Whatever the case, and largely because of the obligations that I have just outlined, it is on the level of couture as opposed to ready-to-wear that my designs have always enjoyed their greatest success.

CHRISTIAN LACROIX, POUF DRESS, 1987

Photo: Roxanne Lowit

Constraints always have their positive side, and in any case I always find the creative process tremendously exciting. I love the feeling of having to make something out of nothing, as though approaching virgin territory or a deserted spot in high summer. It is like a breath of fresh air; it gives you new life and fresh blood. For the creative process is like any other function: the cells die off, wear out and are regenerated like any others. Little by little one grows in skill, in practical expertise and in technical sophistication—which is in fact largely a question of nerve.

CHRISTIAN LACROIX, COUTURE, 1999

Photo: Françoise Huguier

In becoming a public figure—and in this business one has no other choice—one is inevitably exposed to misunderstanding. People often say, for instance, that the fashions I design are heavily influenced by the eighteenth century. But the truth is that I dislike the fashions of that century, except in some of their provincial and Provençal forms, where affectation and studied prettiness give way to simplified shapes and a certain roughness…

CHRISTIAN LACROIX’S AUNTS & HIS FATHER’S COUSINS

‘The costumes of the Arles region have had a deep influence on my designs.

The photo on the left, though taken in the 1920s, shows my aunts in genuine 18th- and 19th-century costumes.

The children in the photo on the right are wearing an ‘old-lady’ style from the Louis-Philippe period,

which was popular with young girls in the 1920s.

These are my father’s cousins, photographed in the 1930s.’

Source: Christian Lacroix, Pieces of a Pattern, ed. & intro’n Patrick Mauriès,

tr. Barbara Mellor (Thames & Hudson, 1992) p. 35

… or in theatrical versions as worn by the turqueries, the French equivalent of the commedia dell’arte.

Jean Etienne Liotard, Woman in Turkish Dress Seated on a Sofa, 1752

I much prefer the styles of the Revolution [1789-1795]…

PETTICOAT & CARACO of GLAZED, HAND-PAINTED COTTON; DETAIL of CUFF. FRENCH, 1780 -1795

‘The motif of flowers, fruits, and insects and the choice of a simple cotton fabric are typical of the taste for

naturalism and simplicity in the late 1780s. The realization of the design and the exquisite silk details,

such as the button and fringe, show great refinement in the name of simplicity.’

Source: Charles Otto Zieseniss, ‘France in Transition’ in The Age of Napoleon: Costume from Revolution to Empire

(New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989) p. 44

… the Directoire [1795-1799]…

DAY DRESS & MATCHING SPENCER of SILK TAFFETA. PROBABLY NEOPOLITAN, c. 1795

‘Reflective of a transitional style, this dress still has the fullness of the round petticoat,

but the waistline has risen slightly up the ribcage.’

Source: Charles Otto Zieseniss, ‘France in Transition’ in The Age of Napoleon: Costume from Revolution to Empire

(New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989) p. 45

HEELED LADY’S MULES of YELLOW FIGURED SILK & CREAM-COLORED LEATHER,

SILK SELF-FRINGE TRICOLOUR COCKADE. FRENCH, c. 1792

‘The tricolour cockade, which identified the wearer as a good citizen of revolutionary France,

could also become an intriguing point of pure fashion.’

Source: Charles Otto Zieseniss, ‘France in Transition’ in The Age of Napoleon: Costume from Revolution to Empire

(New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989) p. 46

… and the Empire [1804-1815].

FRANÇOIS GÉRARD, ‘MME CHARLES MAURICE DE TALLEYRAND PÉRIGORD’, 1804

Diptych composed from images from THE MET (legend text below: same source).

‘The Empire waist that emphasized the bosom was a deliberate rather than an ancillary effect

of the corset’s displacement of flesh. This can be seen in the introduction to the corset’s construction

of gussets, triangles inserted at the chest to support the breasts separately.

From the 1790s to the 1810s, fashions held little refuge for women of ample proportions.

Still, for all the apparent revelation of the natural body suggested by that period’s sheer Neoclassical styles,

evolving technical strategies were necessary to create the newly fashionable high-bosomed silhouette.’

GO TO PART TWO (click or tap banner below)

GO TO PART THREE (click or tap banner below)

CHRISTIAN LACROIX: THREE BOOKS

CHRISTIAN LACROIX ON FASHION

Christian Lacroix

PIECES OF A PATTERN

Christian Lacroix

CHRISTIAN LACROIX

François Baudot

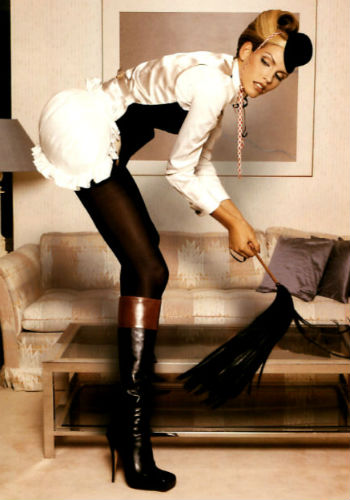

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

FASHION IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

CLICK ON AN IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2022 | All rights reserved

Comments