Vivienne Westwood

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD: VISION AND CRAFT

Selected excerpts from Claire Wilcox, Vivienne Westwood (London: V&A Publications, 2004)

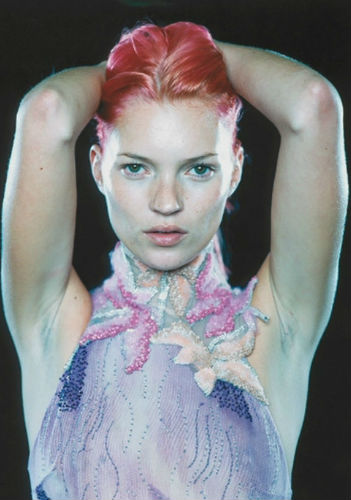

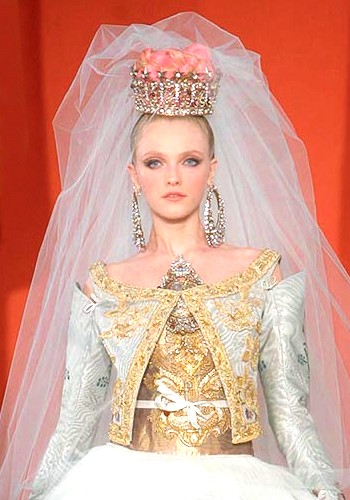

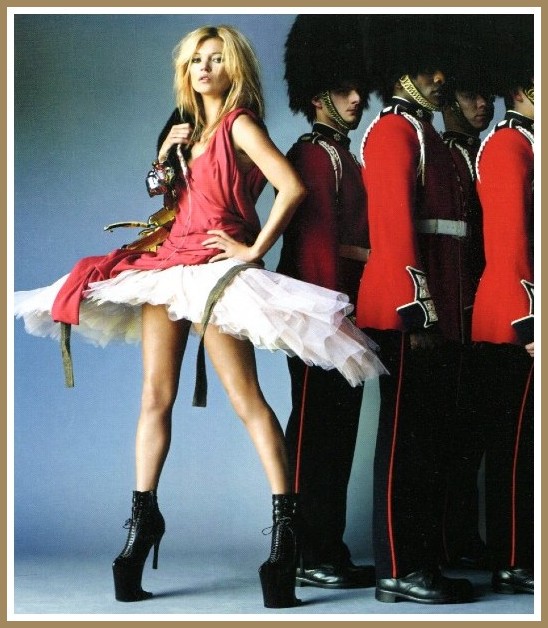

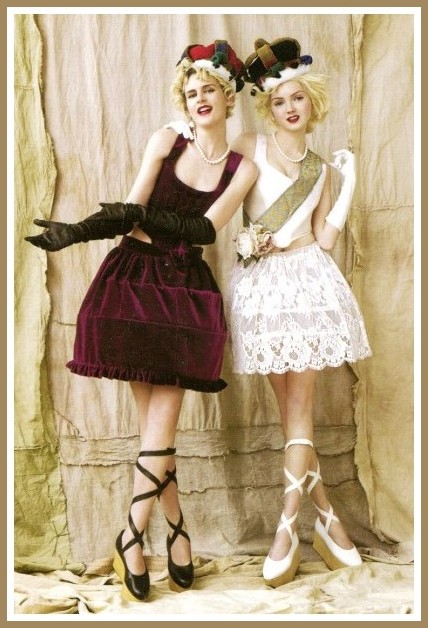

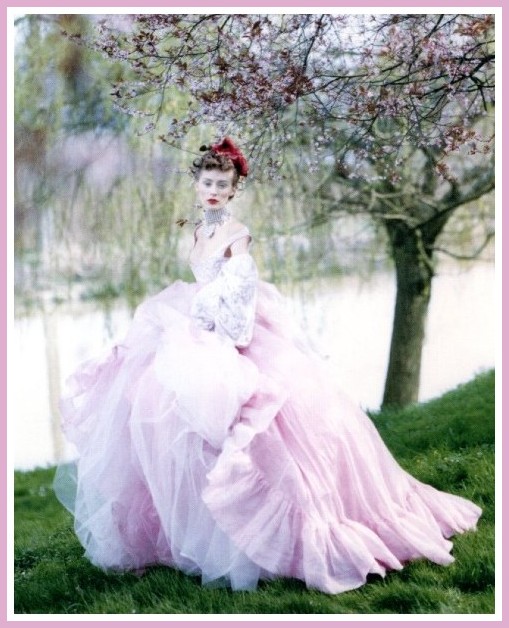

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD, SCARLET JERSEY & TULLE TUTU DRESS

Kate Moss | Mario Testino, Vogue 2009

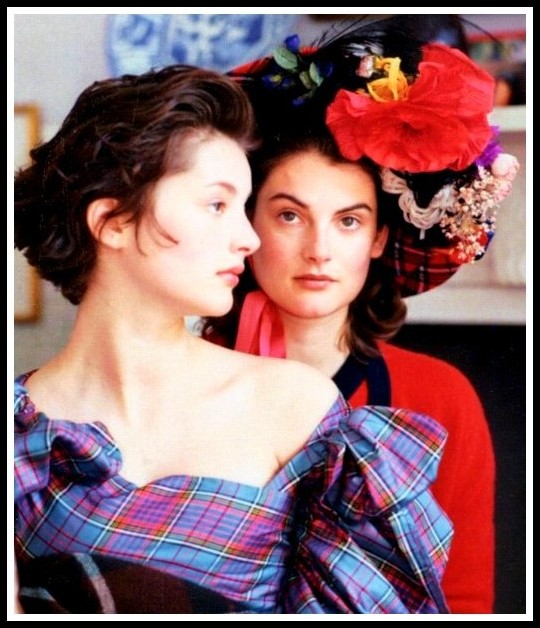

Throughout her career, Westwood has appreciated and revived silhouettes, fabrics and colours that others have overlooked. In her A/W 1987-88 collection, she used natural fabrics at a time when most fashion was driven by ease of care and wear. To the heathery mix of Tattershall check, red barathea, velvet and Harris Tweed, she brought in a gentle parody of establishment styles the clothes of boarding schools, royalty and country wear—giving them a new lease of life.

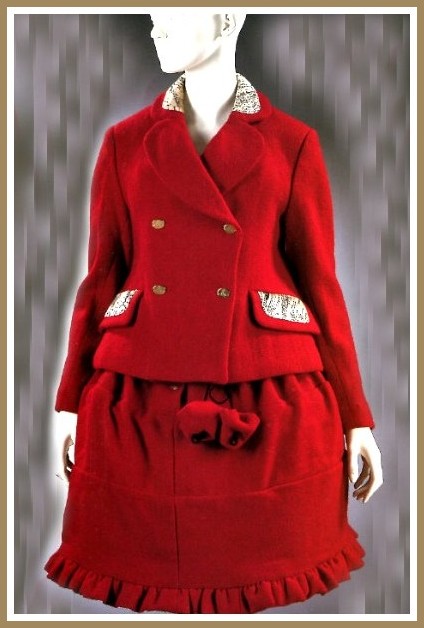

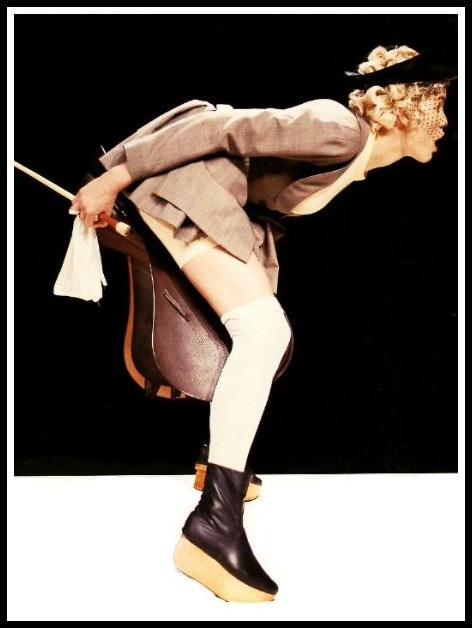

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD, HARRIS TWEED, AW 1987-88

Stella Tennant & Lily Cole | Mario Testino, Vogue

With Harris Tweed Westwood returned to traditional English cutting. She said, ‘This was one of those cardinal points when you stop doing one thing and start doing something else. It was a change of direction—I wanted to make things that fitted.’ This winter version of the Mini-Crini in red barathea imbues the fabric with flirtatious weightlessness. The short, double-breasted jacket was inspired by the princess coats worn by the Queen as a girl. The curved collar and pocket flaps are trimmed with a dress velvet that resembles ermine; it was so expensive that it could only be used sparingly. Curving in at the waist and then smoothly outlining the hips, the ‘Princess’ jacket sits poised on top of the bell-shape skirt, counterbalancing the flirtatious, swaying crini.

Vivienne Westwood, Harris Tweed, AW 1987-88

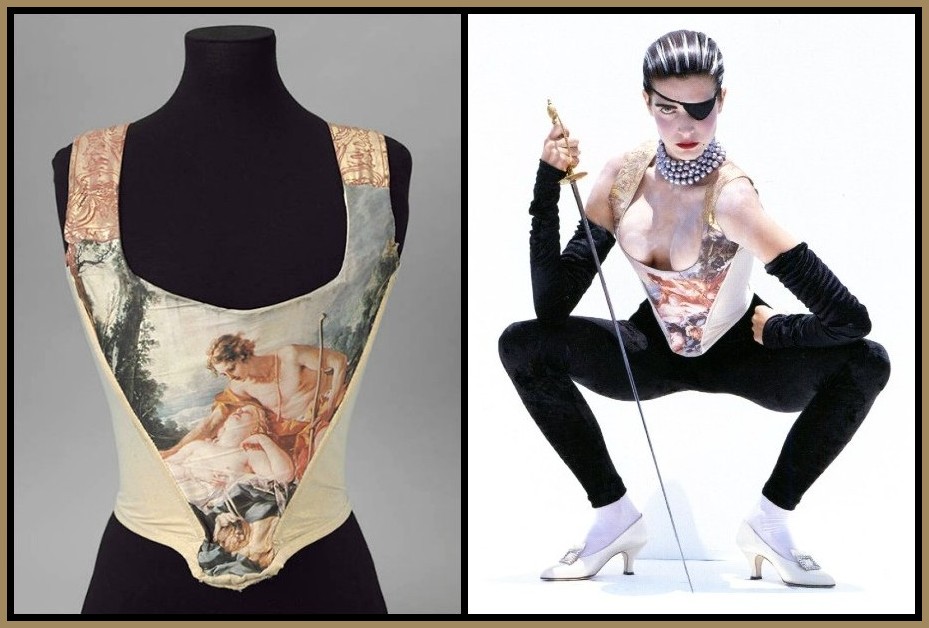

The Harris Tweed collection also included the important Stature [sic] of Liberty corset, based on the eighteenth-century corset, which Westwood reclaimed and reinvented. As Valerie Steele wrote in The Corset, A Cultural History ‘Once women no longer felt that they had to wear corsets when the corset, in fact, was stigmatized—some women consciously chose to wear them. Now, however, the corset was worn openly—as fashionable outerwear, rather than underwear. Long disparaged as a symbol of female oppression, the corset began to be reconceived as a symbol of female sexual empowerment.’

Vivienne Westwood, Corset and sleeves, 1988 | V&A Museum

Westwood’s methodology—research, observation, an ‘archivist’s exactitude’—had been established early in her career, and unlike many designers she was willing to explain her creative processes, confident that although she would be copied, she would always be ahead. ‘Fashion design is almost like mathematics. You have to have a vocabulary of ideas, which you have to add to and subtract from in order to come up with an equation that is right for the times. Here I’ve taken the vocabulary of royalty—the traditional British symbols, and used it to my own advantage. I’ve utilized the conventional to make something unorthodox.’

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD, HARRIS TWEED, AW 1987-88

Models: Sara Stockbridge & Patsy Kensit

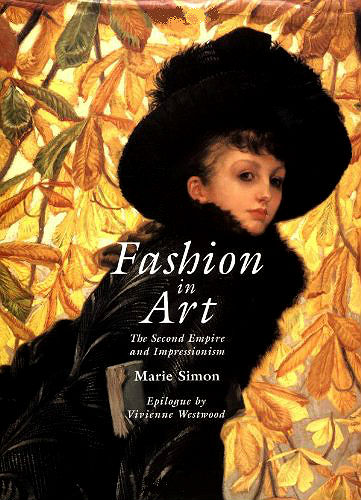

In the epilogue to Marie Simon’s book, The Second Empire and Impressionism, Westwood wrote: ‘Picture galleries are essential to my work, and not merely paintings containing costumes but also landscape and still-life, in which harmonies of colour, design and movement can germinate so many fashion ideas.’ Westwood explained in the book accompanying the V&A’s 1997 exhibition The Cutting Edge: Fifty Years of British Fashion 1947-1997: ‘Fashion as we know it is the result of the exchange of ideas between France and England,’ and by this time, having shown in Paris and become increasingly familiar with the depiction of aristocratic dress in French art, Westwood could draw on this cultural marriage. ‘On the English side we have tailoring and an easy charm, on the French side that solidity of design and proportion that comes from never being satisfied because something can always be done to make it better, more refined—hence an elaboration that always stops short of vulgarity and then that je ne sais quoi, the touch that pulls it all together.’

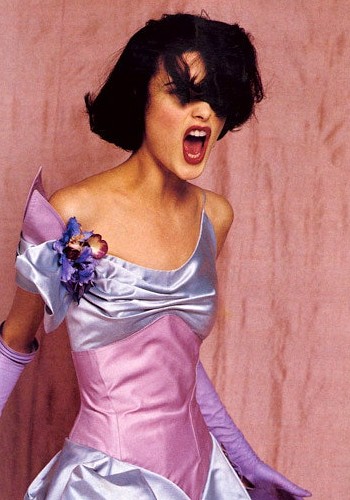

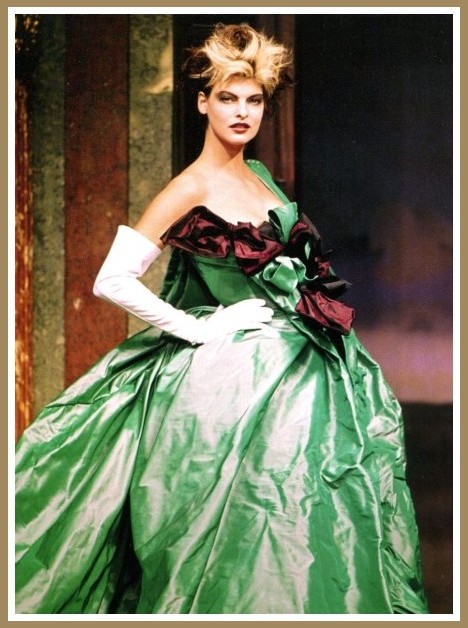

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD, WATTEAU EVENING DRESS, 1996

Linda Evangelista | Steve Wood

Marie Simon: ‘In recent years it is perhaps Vivienne Westwood who has succeeded in interpreting the pictorial tradition most audaciously, in collections sparkling with idiosyncrasy. Ambassadress of Boucher, Ingres and Tissot in turn, she resurrects the corset, the crinoline and the bustle. Encumbering and feminine symbols of a life of idleness, they had been assumed to be tucked away forever in the catalogues of the history of costume and only displayed in the showcases of museums. Yet here they are again, freshly dusted down, flaunting themselves on the catwalks of the Cour Carrée. “Mini-crinis” and bustles steady the tottering walk of tall, slim girls perched on platform soles and crowned with unruly ringlets. They parade themselves before our astounded eyes, defying logic, time and rationality. For fashion, frivolous and changeable, blithely spins its threads between periods and people. And to gather up and stitch together the scattered pieces, as it saunters on its way, it leaves behind, in Cocteau’s words: History, sitting and plying the needle.’

Vivienne Westwood, Portrait, AW 1990-91

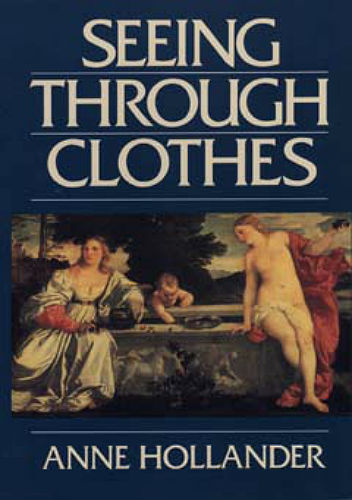

Since the mid-1980s Westwood’s collections had been the antithesis of casual wear. Hers were complex, formal, indoor clothes; by modern standards, the models were overdressed, and the fabrics high-maintenance, but this merely served to emphasize Westwood’s singularity. In the introductory scene to her documentary film Painted Ladies [see video below], a series of ‘dressed up’ characters flit through a gallery in the Wallace Collection, admiring the old masters. Westwood’s preoccupation with the past is expressed using clothes as a cultural carapace; each ensemble is laden with historical references, imbuing the wearer with a self-awareness, a pleasure in being observed and ‘read’. As Anne Hollander wrote in Seeing Through Clothes, ‘It is pictorial art that dress most resembles, and to which it is inescapably bound, in its changing vision of what looks natural. In order that the look of the body might always be beautiful, significant, and comprehensible to the eye, ways developed of reshaping and presenting it anew by means of clothing.’

Vivienne Westwood, Anglophilia, AW 2002-03

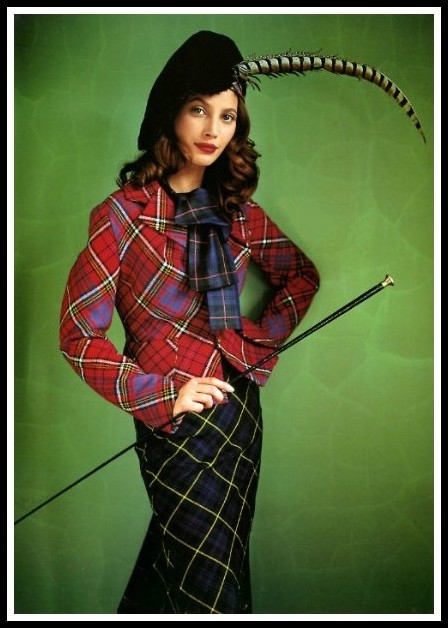

The title ‘Anglomania’ (AW 1993-94) referred to the French passion for all things English—literature, language, clothing and even food— that prevailed during the 1780s, when pre-revolutionary, foppish styles were replaced by the plainer English aristocratic look. Westwood’s fascination with English and Scottish traditions—as source of inspiration and subject of parody—was reiterated in Anglomania with mini-kilt tartan ensembles, and for the same collection the Locharron Textile Mill created a special tartan for Westwood called the ‘McAndreas’, after her husband Andreas Kronthaler. In her essay on ‘Anglomania’ in The Englishness of English Dress, Rebecca Arnold wrote of the bravado of Westwood’s approach to tartan, which the designer has utilized more successfully than almost any of her peers: ‘Her designs demand a present that is as dramatic and purposeful as that inhabited by, for example, MacDonnell of Glengarry, painted by Raeburn in the late eighteenth century, in what was itself a wistful mythology of Scottish identity. For Westwood, women can cut just such a dashing and heroic figure as men, in clothes that are just as much about constructing an idealized, theatricalized femininity as they are about representing national identity.’

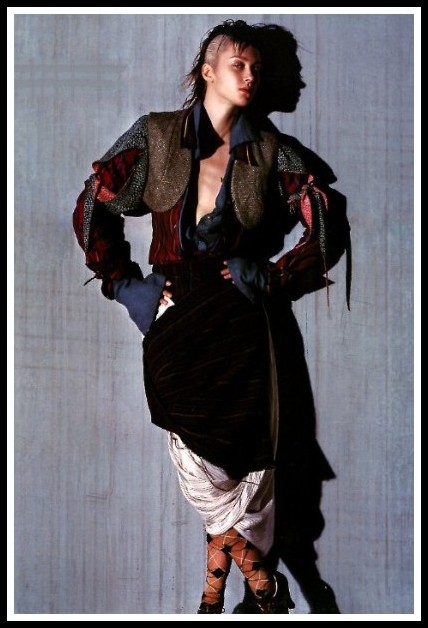

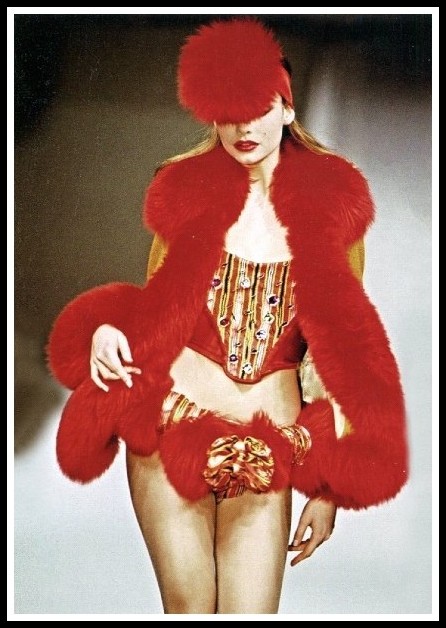

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD, ANGLOMANIA, AW 1993-94

Models: Honor Fraser & Violet Fraser

Treating fabric like a living mass Westwood uses folding and pleating to create spaces between body and cloth, exploring different ways to create volume and allow it to stay, like air pockets. In a recent conversation Westwood held the two edges of a sheet of A4 paper together, but not quite aligned, demonstrating how this immediately gave a twisting dynamic to the inert paper, almost as if she was trying to find another dimension. She has described herself as having ‘spatial intelligence’: ‘I’ve got a real sense of three-dimensional geometry. I can look at a flat piece of fabric and know that if I put a slit in it and make some fabric travel around a square, then when you lift it up it will drape in a certain way, and I can feel how that will happen.’

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD, ANGLOMANIA, AW 1993-94

Christy Turlington | Mario Testino

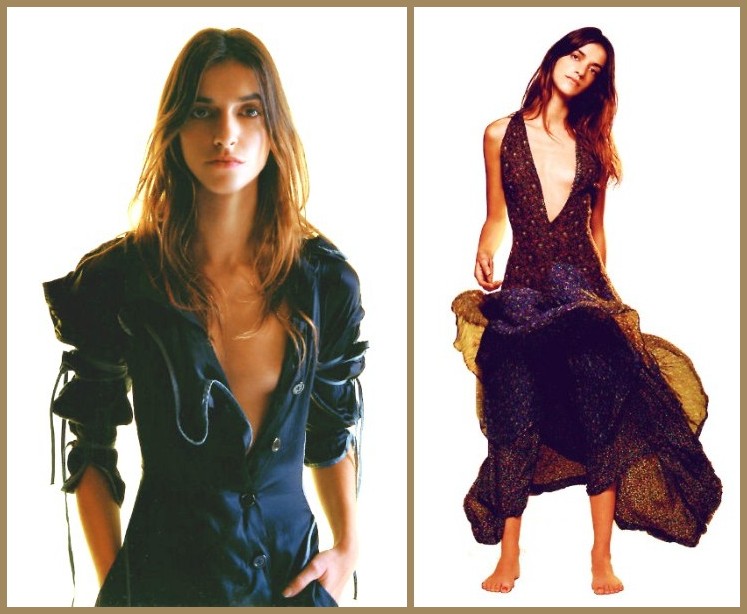

Starting with ‘Summertime’ (SS 2000)…

… and continuing in the collections ‘Winter’ (AW 2000-01)…

… ‘Exploration’ (SS 2001)…

… ‘Wild Beauty’ (AW 2001-02)…

… ‘Nymphs’ (SS 2002)…

… ‘Anglophilia’ (AW 2002-03)…

… and ‘Street Theatre’ (SS 2003)…

… Westwood continued to explore the myriad of ways fabric can fold over the body. She described the process: ‘It’s just getting form by putting fabrics together that do not have the same angle. The fabrics are all at slightly different angles so that they create a form, and the nice thing about it is that it’s the sort of look that we are after—tailored/non-tailored, spontaneous and arty-looking, if you like, and a bit futuristic in the way that the clothes are shaped not necessarily with the purpose of fitting the prominent point. It’s to do with the fact that you do not care about the bust or waist anymore, yet you do have to be aware of them to make sure there is room in the fabric for them. But to give this lively look to the clothes—because it’s incredibly lively-looking and nervous-looking—you are purposely not hitting the crucial body points. The thing about them is that you can wear them without caring at all, and they are just working for you all the time, showing your body—it’s very dynamic. It’s amazing, even off it looks dynamic. It’s augmenting body movements in some way, carrying them on after they have finished.’

Vivienne Westwood, Street Theatre, SS 2003

Self-taught, but mistress of her craft, Westwood’s fashions are often sparked off by historical styles but have a timeless appeal of their own. Steeped in references and allusions, they are at the same time exercises in discipline and control. As she said, ‘I work from a simple principle that a geometric fabric piece will have its own terrific dynamic. The technique comes first. That’s why I never dry up for ideas, because when you master a technique, self-expression is automatic.’

Vivienne Westwood, Street Theatre, SS 2003

One of the most characteristic aspects of Westwood’s design is its historicism. ‘I take something from the past which has a vitality that has never been exploited—like the crinoline—and get very intense. You get so involved with it that in the end you do something original because you overlay your own ideas. So there’s your own individuality, your own particular way of looking, and what you see cements it all together. Things are never quite as they were, so even if you tried to copy a traditional garment exactly you couldn’t because you’d have to use a modern way of making it. The idea is something that comes with the form, and it grows as you do.’

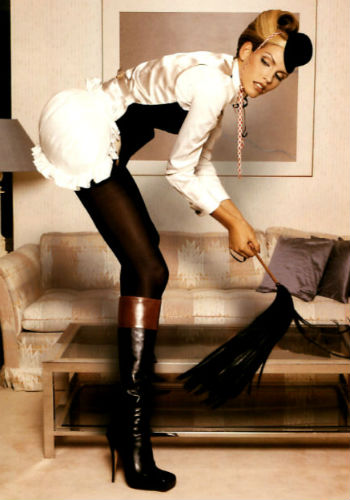

Vivienne Westwood, Five Centuries Ago, AW 1997-98

The importance of Westwood’s revival of the corset is clear. Karl Lagerfeld claimed that the corset was one of the most significant fashion ideas of the late twentieth century. ‘Her relationship with historical dress is on an entirely different level from any other designer,’ commented Susan North, V&A Curator of eighteenth-century dress, who was particularly struck by the accuracy of Westwood’s corsets. However, far from being ‘costume’, they are a perfect example of historicism transformed into a modern garment. For, despite her romanticism, Westwood is also practical, designing corsets with removable sleeves for evening, and utilizing stretch fabrics that look constricting but in fact move with the body. Costume historian and eighteenth-century specialist Aileen Ribeiro observed: ‘She has a quintessentially English way of looking at the past slightly offbeat, informed by practical knowledge and intuition about the way that historical garments work.’ Her corsets were modelled on the 18th-century style, flattening and raising the bosom. This corset is photographically printed with a detail from François Boucher’s Shepherd Watching a Sleeping Shepherdess (1743-45).

Vivienne Westwood, Portrait, AW 1990-91

Westwood’s technique can also be compared to that of Madeleine Vionnet (1876-1975); both share the same way of working in the round on a dressmaker’s dummy rather than from sketches, and of employing geometric principles in their cutting. Westwood said, ‘Art must be anchored in technique; this means the manipulation of materials—in my case my materials are essentially the human body and cloth. It is my job to make the cloth give expression to the body of a human being. One must constantly judge and manage the detail in terms of the general effect one is trying to create so that the form is the idea: a beautiful form is a beautiful idea—this is design.’

Vivienne Westwood, 1994 | Photo: Paolo Roversi, Vogue

In Pagan I, Westwood paired structured tailoring and drapery. The lightly boned, fine wool check jacket has a curved neckline cut to below the bust to reveal the boned draped white silk corset. It is cut shorter at the back to accommodate the matching’ Centaurella’ bustle skirt. Westwood combined a style of pleating used in the 18th-century sack-back with a 19th-century technique of holding fabric away from the body with padding: ‘I had noticed in the back of an Empire line dress four little silk balls which I assumed were there to hold the dress away from the body. I realized I could insert them into the pleats to make them more column-like. This skirt is full of movement—it’s held there but it’s really away from you. It can swish around, it really moves a lot when you walk. It’s very lively.’ Because it was so short, the skirt was worn with silk shorts.

Vivienne Westwood, Pagan I, SS 1988

Westwood’s overriding gift to fashion is her conviction that clothing can change the way people think. ‘I think that the real link that connects all my clothes is this idea of the heroic.’ She has great faith in fashion as personal propaganda, as mental and physical stimulation, saying ‘clothes can give you a better life’. It is this vitality that is unique, rather than her cut and construction, original as they are. As Alix Sharkey wrote in The Observer Magazine, ‘For her, clothes should intensify and refine the wearer’s sense of physical presence; provoke a reaction, charge the atmosphere with sexual and political tension; they should directly alter the physical reality of the world around them. Clearly, this kind of clothing poses questions, and challenges us to explore, to consider the unknown. It can make us uncomfortable, this fashion that works like a drug, that alters our state of consciousness.’

Vivienne Westwood, Pagan I, SS 1988

Vivienne Westwood has said ‘I think my clothes allow someone to be truly an individual’ and wears her own clothes with panache—usually with a silk handkerchief from Tie Rack round her neck and often an antique spider brooch. Her clothes are characterized by an apparent complexity but, complimented recently on a green gingham blouse which lay in folds and drapes across the torso, she unfastened it to show that it was simply made of squares. Her use of familiar, often modest materials married with dynamic structure allows us to see the potential of fabric and form as if for the first time. Like the green gingham blouse, Vivienne Westwood’s clothes seem fresh and surprising; they offer an alternative; they do seem heroic.

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD – FASHION: THREE BOOKS

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Three Chapter 8

̶ I went to a Vivienne Westwood show in London.

̶ That’s a hot ticket!

̶ Yeah.

̶ How’d you get it?

̶ Kassia Ibarra. She’s a friend.

̶ Did you like the show?

̶ I did. Harris Tweed. In particular a bodice, cape and skirt on a ravishing redhead.

̶ I like Vivienne Westwood. I like her quirky originality.

̶ Yes, it’s refreshing.

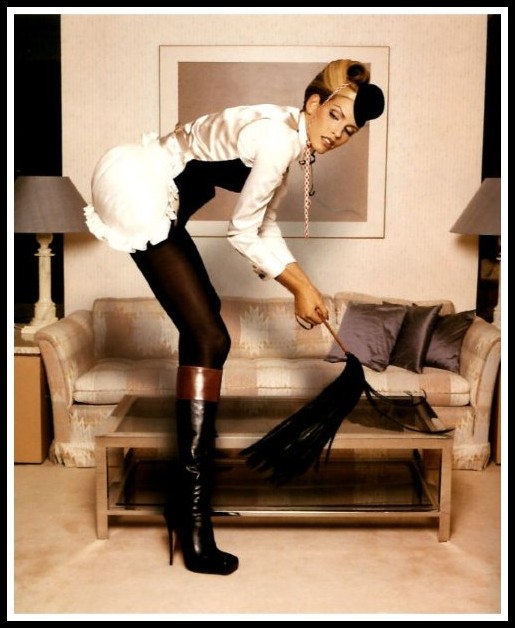

Vivienne Westwood, Dressing Up, AW 1991

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 16

Thursday you came home to find my birthday presents on your bed: an excess of Anglomania. Unable to decide what jacket to choose, I’d bought you three Vivienne Westwoods. I hoped you’d interpret it not as a sign of my insecurity but as a token of my knowing what would suit you: In charcoal and white, a pinstriped twill with an asymmetric hem and peaked lapels; in navy denim, a military jacket with a double-breasted placket and gold-striped cuffs; in black leather, a biker jacket with variable fastenings. You had the grace to interpret as haste my panicky indecision.

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD, ANGLOMANIA JACKETS

Voodoo (leather) | Chevalier (pinstriped twill) | Military (navy denim)

Thursday evening, at The Flask, we reminisced in laughter with Ariane and her Nicaraguan lover, moving on to share present news with equal good humour. In your new biker jacket, your white jeans and striped top, you were the coolest incarnation of chic: Was the black-and-white look your way of teaching me not to go over the top? Friday you wore the charcoal-and-white pinstripe to work and in the evening, at your surprise party at Gram’s, you were a hit in your military jacket and zip-pocket pants, your hair slicked back, braided ponytail wrapped into a bun: Was it you way of teaching me that one can pull anything off, provided the inner and the outer work in harmony?

Vivienne Westwood, On Liberty, 1994-95

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan, Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms – Read the first chapter

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD FASHION: TWELVE LOOKS

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD: ‘DO IT YOURSELF’, 2009 | RAINPROOF VELVET TRENCH COAT, 1992 | ‘PORTRAIT’, AW 1990-91

Photos for Vogue: Patrick Demarchelier | Javier Vallhonrat | Declan Ryan

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD: ANTIQUE ROSE SATIN DRESS, 2006 | DANGEROUS LIAISONS JACKET, 1994

Photos for Vogue: Craig McDean | Andrew MacPherson

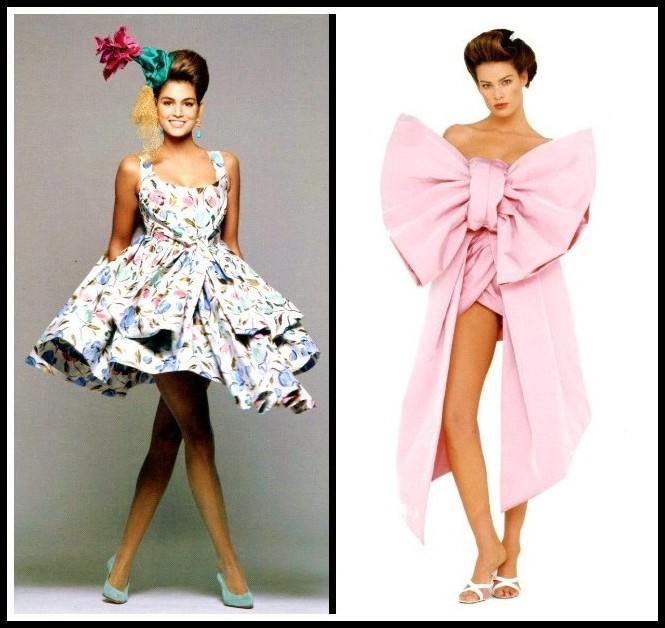

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD: ‘THE NEW DRESSING UP’, 1988 | ‘CAFÉ SOCIETY’, 1994

Photos for Vogue: David Bailey | Andrew MacPherson

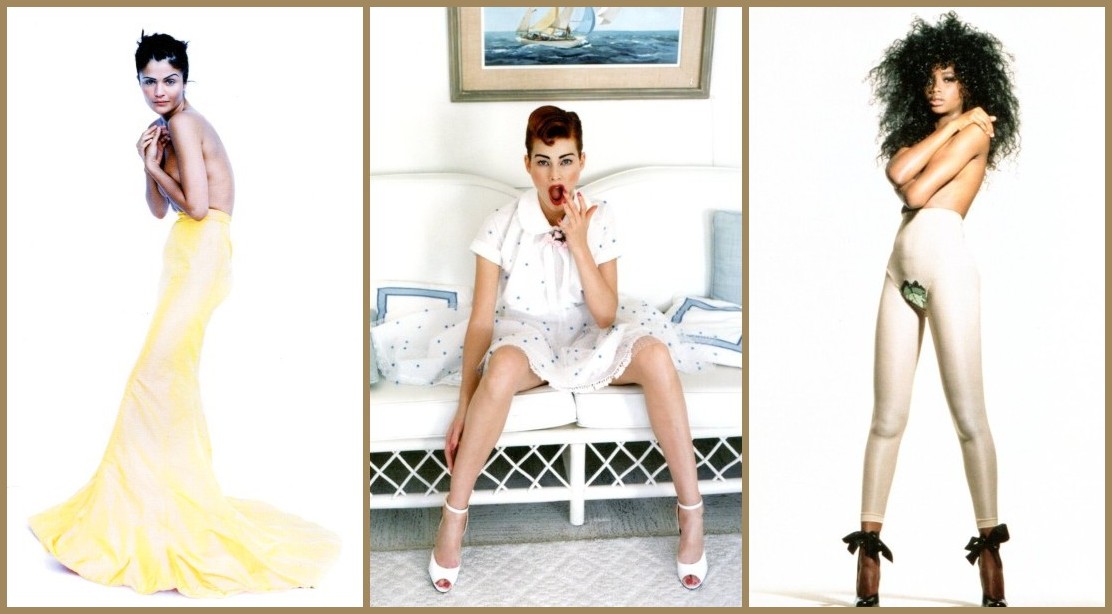

Vivienne Westwood: Erotic Zones, SS 1995 | Photos: Andrew Lamb, Vogue

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD: EROTIC ZONES, 1995 | EROTIC ZONES, 1995 | VOYAGE TO CYTHERA, 1989

Photos for Vogue: Mikael Jansson | Mario Testino | Steven Klein

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD ON FASHION: PAINTED LADIES (1996)

Part 1: Nobility, Virtue and Morality

Part 2: Aesthetic Lust

Part 3: Luxury and Frivolity

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD: ANGLOMANIA (AW 1993-94) FASHION SHOW

Susie Bick | Backstage at Anglomania

Vivienne Westwood: Anglomania, AW 1993-94

Susie Bick | Backstage at Anglomania