Sonia Rykiel

SONIA RYKIEL ON SONIA RYKIEL : CELEBRATION

Abbreviated from Sonia Rykiel, ‘Celebration’ (excerpt), tr. Claire Malroux, in On Fashion, Shari Benstock & Suzanne Ferriss, ed. (Rutgers University Press, 1994).

All photos in this section (except banner photo) courtesy of Vogue.

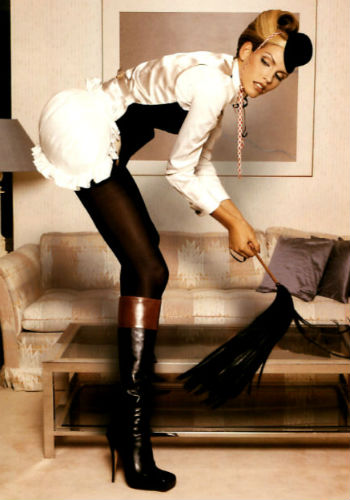

You bet I can see that woman, the one I have been pursuing for twenty years, the one who tempts me, hiding behind fabrics, baring a shoulder, slipping on her dress inside out, turning it right side out and then jilting me to run after that man who was eyeing her. She is beautiful, elusive, quiet, calm, but when I think I’ve caught her, she is already gone dancing from one bank of the Seine to the other, a coin struck on one side with ‘Woman’ and on the other with ‘Man.’ She kicks off her shoes, crosses the bridge with outstretched arms and eyes lifted to the sky, wears men’s sweaters with tight skirts or ample slacks with close-fitting pullovers, unpicks her hems, dresses warmly in April, lightly in May.

Sonia Rykiel | Fall 2009 Ready-to-Wear

As in stories of love, eternal love or impossible love, her dress is a plaything like a lover following with his hands the lines of the body without touching it, without coming to rest and who then yields. To get to know oneself. Or to lose one’s heart to a dress designer who would understand the body, the whim of the moment, the color of skin, the softness of complexion, the frailty of the soul. To give one’s body to the fantasies of another, his obsessions, his passions, to surrender heart and soul to a stranger who would adorn the skin with his idées fixes, his dreams. Aren’t we mad to let them move us about, push us around, wrap us up, reproduce us so we are all the same or nearly so, all of a mold with perhaps a difference in the voice, in a gesture.

Sonia Rykiel | Fall 2009 Ready-to-Wear

Not knowing how, I was able to do otherwise. My creation knows no stages, just odd moments, a skirt, a pullover, a dress. Fashion, like history, parades, all lights turned on it. It spangles and glitters, studded with silver and gold. It sparkles from head to foot, bursting out triumphantly, gloriously, luxuriously, demented flesh, trailing skirt, hooked-up bra, a long string of dummy pearls, gilded shoes, bare legs, bare head, bare chest. It is said that everything may be read in a face; me, I reckon that all may be read in clothes, but if the face is supposed to be radiant, clothes come alight only when the body moves.

Sonia Rykiel | Fall 2009 Ready-to-Wear

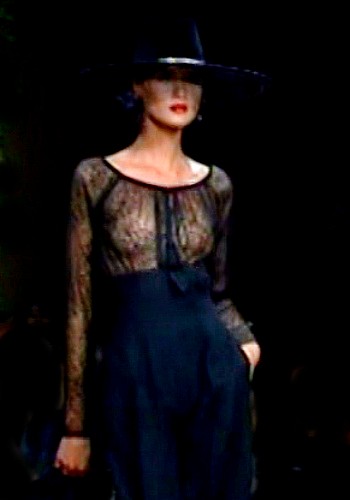

She is transparent, inside and out, as if body and dress were mirrored images of each other, each the consecration of the other. You are being watched, you know, robbed, betrayed, nothing escaping us, neither sound nor thought. You know that we are lying in wait, that the fatality of creation prompts us to lie, that the ephemeral which is the natural condition of fashion forces us to turn inward that which the previous season faced outward and that even if the basting is strong, the result of real know-how, it is inadequate to propose a lifelong style. One must be ambiguous and real, ritualistic and vague, present and absent, lying and truthful, but in the pleasure of doing there is the contentment of taking without being noticed. Fashion unstitches, restitches and starts anew a hundred times over. It is mystery everywhere and yet it is nowhere. It evades, lies but invents, turns its coat because coats must be turned to understand better, like seaming turned either in or out, yet right, well cut with or without hem, must fall right. Troubled by the folds of life’s creases which are never in the right place and which it must refold to its plan.

Sonia Rykiel | Fall 2009 Ready-to-Wear

He who utters the word fashion knows not what he says. Lean closer to hear the rustle of fabric, the words of the artist, his passion for dress. Lean even nearer to see that he is not destroying but having new thoughts, repositioning, reworking, reshaping the same form on which he has already thought, positioned, worked, shaped, everything being drawn from the depths of the eternal and essential memory he has of the object already conceived long ago. The first sweater and the second, the third and the thousandth and that of tomorrow, all related like the pages of the same novel, a distorted unfinished text seeking a companion for the next season, neither too distant nor too near, unbuttoned in the right place, slit on the proper side. Are we not destroying fashion, chasing it around like this? Every six months, a kick in the behind; it enters through the main portals and is made to exit down the back stairs. It climbs in again through a window, skirts longer, more mobile, closer fitting. It lasts merely the time of a Summer and leaves wider, padded at the shoulders. It’s Winter once more. It’s molded, draped to the ground, coat upon coat, absurd. Could we not evolve rather than destroy, work on clothing like one works on a book and avoid, we the creators, being ‘consecrated’ or ‘desecrated’ every half year?

Sonia Rykiel | Fall 2009 Ready-to-Wear

Twenty years ago, I invented an image, a paper woman written in the folds of the fabric, the knitted threads, the colors of the flesh; I bestowed on her visible signs of luxury, joy, colors, a modern package, a day-to-day destiny, a pure line with hazy outlines, a story. She ran away and I caught her again; I left and she came back to me. A novel is a novel only by comparison with another novel. A dress is a dress by comparison with another dress; so I turned it, I sewed its name inside, I pinned it to a wall. In its folds, I sounded all the notes, sought out the differences, folded the print to give it shape. I leaned to the left to sound its heart, on the right I sewed badges, pasted trinkets. I unpicked the hems for freedom and folded the seams so they can be felt, be seen.

Sonia Rykiel | Fall 2009 Ready-to-Wear

I wonder if it is you or I who dictate fashion. If it be not you compelling me to shorten, lengthen, widen, remove the belts, lengthen again, no more red but some yellow and blue and then red again. If you are not there, you, behind me to see that I unstitch the hems or overstitch them, that I sew on beads, spangles, and even flowers, if you don’t push me to tighten the waist or lower it onto the hips, to remove the petticoats, add flounces, to show the stitching and to hide it, if one season you revel in luxury, sumptuosity, gilt, and then another season in despair (which is not black but rather a look), if you don’t pull me apart to attach, tuck, close or open, draw aside to peep at skin, the luster of the flesh, the texture of the fabric, pull the threads to gather the material, fold the muslin to imitate a book. If it be not I on the couch and you on the chair and that naturally, without appearing to, it’s you who dictate fashion.

Sonia Rykiel | Fall 2009 Ready-to-Wear

It is an art to dress, attract the other, capture him. The difficulty of being ‘natural’ or ‘sophisticated,’ in ‘good taste’ or in ‘fashion,’ modern or ‘outside of fashion,’ resemble a Madonna or nobody. In the world of fashion, ‘fashion’ is refashioned each time but one remains oneself in one’s ‘own world,’ in one’s own style, that’s what’s difficult. To be at the same time excessive and sober, sincere and false, or mad, not to be a mere image but a true illustration of woman. Short-skirted doll, high heels, or long-skirted idol, flat heels, inconstant woman playing her role from day to day. One can work without problems, simply with drawings, happy pros—I know some of them—but behind the dress, the painting or book, the object exhibited, the perfect object, ‘beautiful in its perfection,’ there are in each fold, in each page, traces of work, reflection, scrapping, fresh starts. It is difficult to build a legend, to create history, hold a name high, consecrate it every six months. Often I looked at it, that finished dress, I smiled because it was beautiful and had cost me untold suffering. The creator is out of step, since he must be ‘before’ but at the same time ‘actual.’ That he lives in the past also, it’s his role, since he must be a witness. But he must see more clearly, further ahead. The creator’s paradox is the play between before, during and after, the passing of these three periods, attention to the past, present and future, shaping each one, folding it into the others and then creating the work of art. What counts is style.

Sonia Rykiel | Fall 2009 Ready-to-Wear

Style is the difference between one who creates and gives life to a work and one who creates a work without giving it life. It is the folding and unfolding of a work in time. You stitch, you unstitch, you shape, you unshape, you reshape, you create. To build, construct, invent and destroy, put into place, a moment, a dress, a page, a line. Before, after, to find the beginning of the dress, the part which touches first, which caresses. Author, actor, that which is seen and that which remains, that is work. I erase, I scratch out, I turn the page. That’s luxury. Then I return to my old sweater, my old skirt. That’s even greater luxury. Nothing marked me out for dress designing except a knack of organization, mixing, disrupting, and destroying truth. Create an illusion, but convincingly, opening out in the fold, flaring out, caress the seams to reveal the body and then fold them in again to play with the slits, the openings. Light, color, shadow, not necessarily black but a gray edged with red like a November sky. Woman is institution and what’s good about institution is to be able to break away from it.

Sonia Rykiel | Fall 2009 Ready-to-Wear

FASHION BY SONIA RYKIEL : SIXTEEN LOOKS

Selected from Geneviève Lafosse Dauvergne, La Mode selon Sonia Rykiel (Paris: Éditions du Collectionneur, 2003). Image captions translated here by Richard Jonathan.

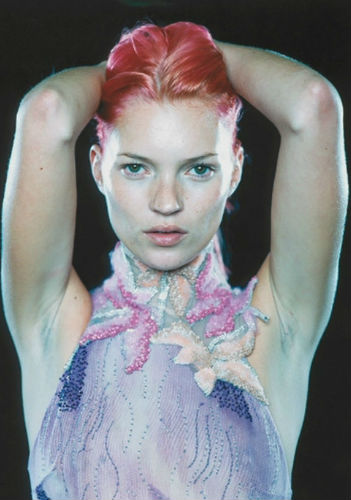

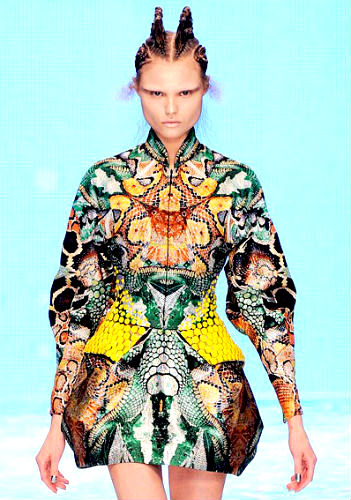

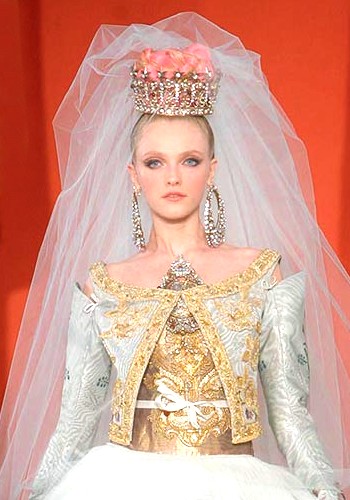

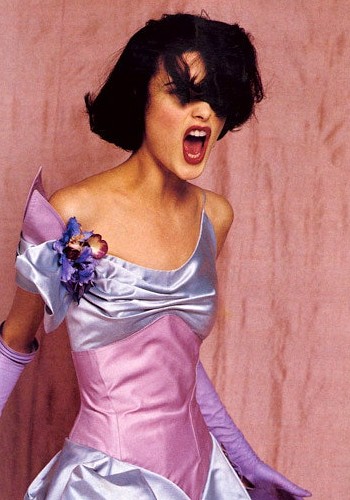

SONIA RYKIEL | FW 1994-95

‘A very Saint-Germain-des-Prés (Left-Bank) Parisienne’

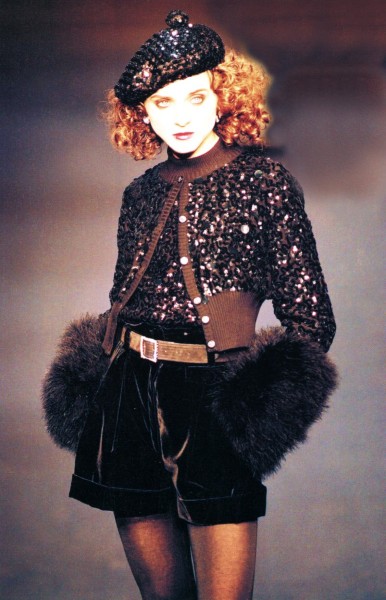

SONIA RYKIEL | FW 75-76

‘Exposed seams: a Rykiel signature’

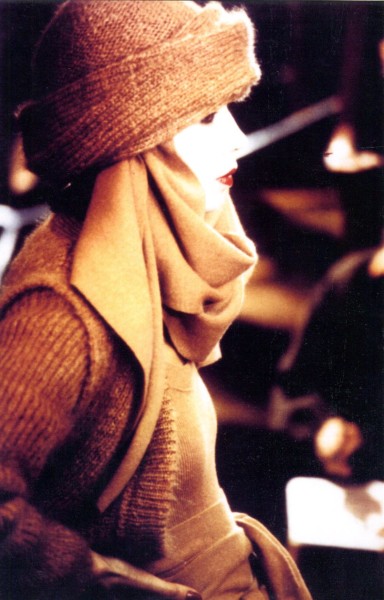

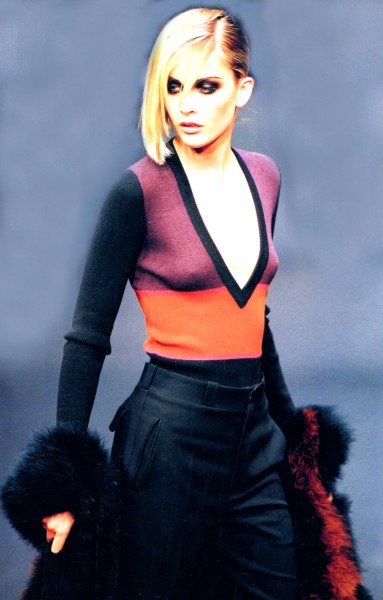

SONIA RYKIEL | FW 97-98

‘The vertigo of the décolleté according to Rykiel’

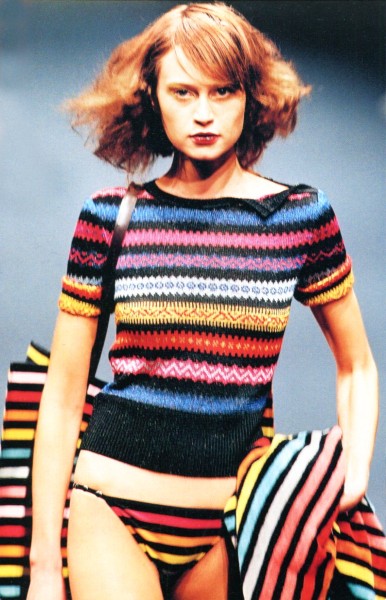

SONIA RYKIEL: SS 2000

‘Knits having fun with stripes, color mixes dancing to jacquard rhythms’

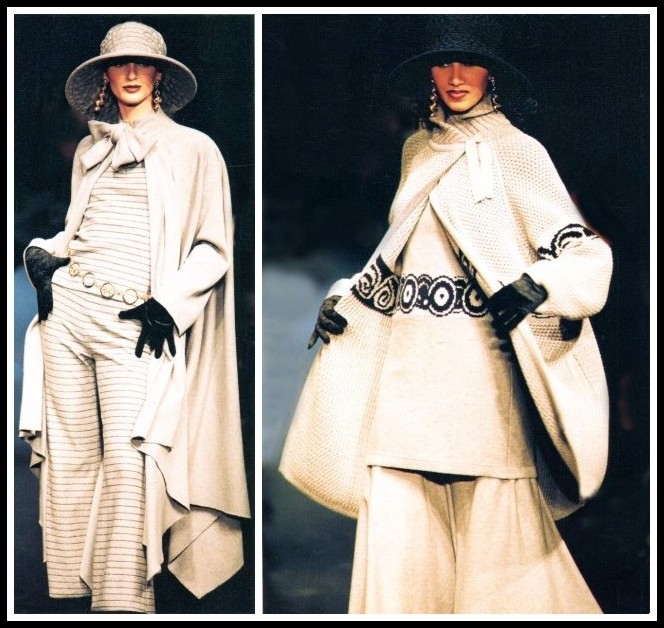

SONIA RYKIEL FW 93-94

‘The Rykiel allure: a large cape over a jersey pant suit’

‘Slavic inspiration: a warm outfit with Arabic motifs’

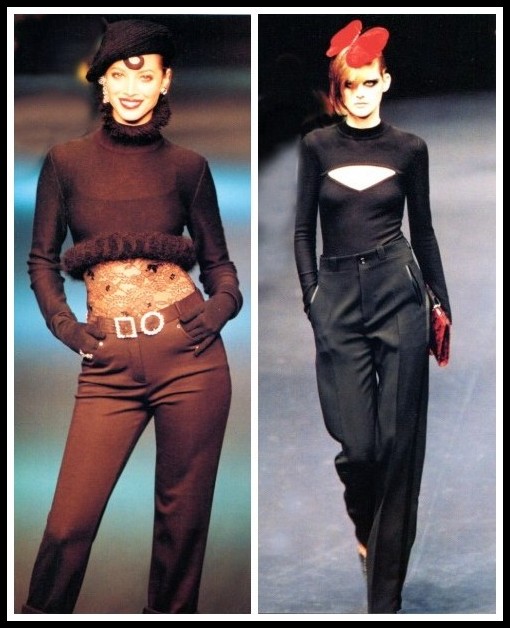

SONIA RYKIEL: FW 94-95 | FW 97-98

‘Double play: jeans and lace, relaxation and sophistication’

‘Androgyne silhouette in trousers and close-fitting cut-out décolleté top’

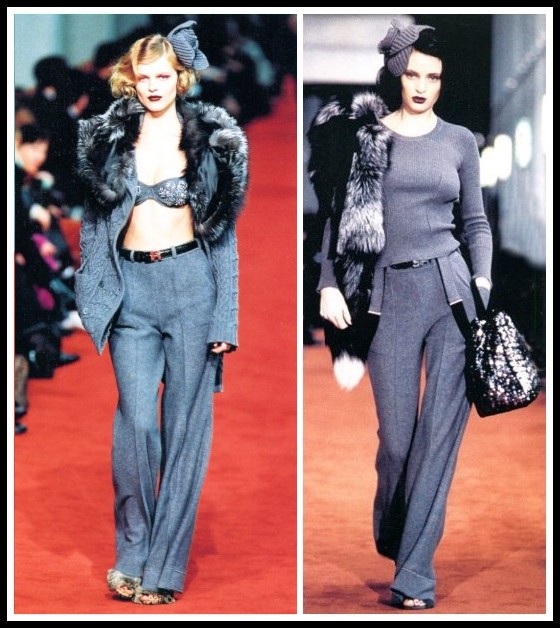

SONIA RYKIEL FW 98-99

‘Shabby-chic, masculine tweed suit feminized by a glitter bra and fox-fur collar’

‘Another very Saint-Germain-des-Prés (Left-Bank) Parisienne’

SONIA RYKIEL: FW 96-97 | FW 94-95

‘A bride come in from the cold and the Steppes’ | ‘Marabou, a very Rykiel sensual softness’

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS ON SONIA RYKIEL

Abbreviated from Hélène Cixous, ‘Sonia Rykiel in Translation’, tr. Deborah Jenson, in On Fashion, ed. Shari Benstock & Suzanne Ferriss (Rutgers University Press, 1994).

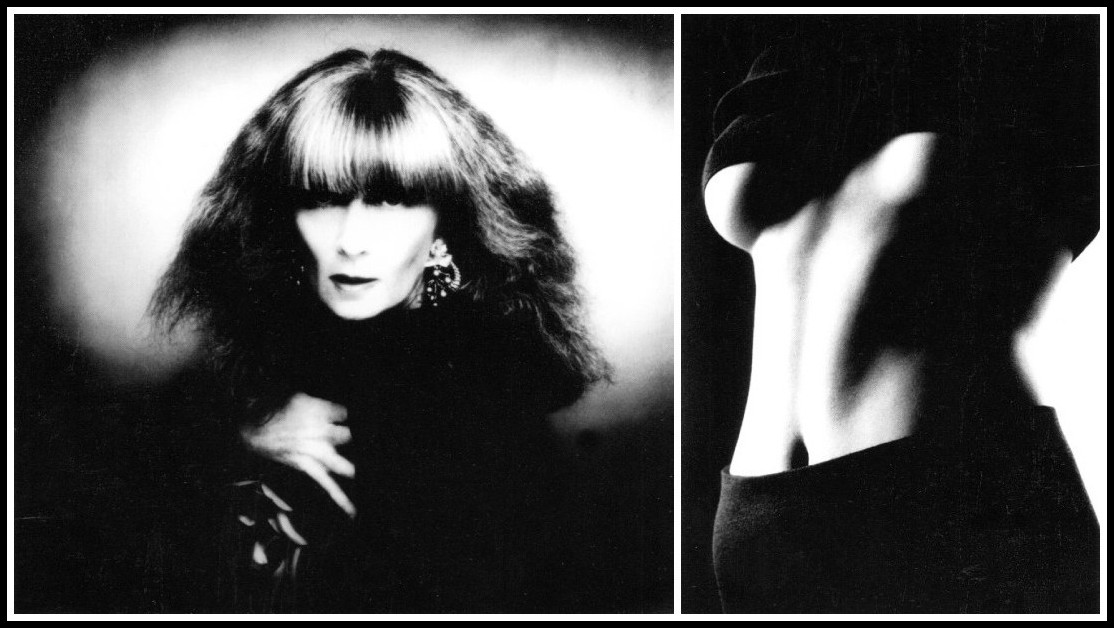

Portrait of Sonia Rykiel | Advertising photo for Sonia Rykiel ‘Le Parfum’

PHOTOGRAPHS BY DOMINIQUE ISSERMANN

My starry jacket: it lives in my closet like a discrete primitive deity. Like an allusion to night. We watch over one another. Sometimes I wear it; sometimes it wears me. Modestly, my jacket manifests the luminous presence of the night, up above and in my closet. The great outside is also inside. Sometimes I wear a warm starry night on my person. Night in a woollen jacket? Why not? Nothing makes one think more of what there is of night in each woman, of what is soft, silently black, brilliantly soft and black. It is the starry bosom, which modestly continues to envelop us. All this, this world, in this jacket? Yes, because it is so simple. All black with small crystals of strass hung like stars in the mildness of the night. It is not an outfit; no detour, no disguise. Just ‘night’: as a child would design it, with all its attributes, the Great True Night with stars pinned on the great black bosom. All this to draw attention to the enigma of this garment cut from a simple bit of warm night: there is continuity between world, body, hand, garment. The designing hand of the child: night, the hand stuffed with stars, the hand making a starry jacket. From sky to body, the stars wend their way, in neat formation.

This garment comes from very far away. I had never seen it, I have always known it. It comes from the origins. It comes from the trace of the immemorial origins in the farthest depths of my memory, where memory does not remember itself, has no images, is still nothing more than the movement of life. This garment comes from an Orient, from an East always beating in the heart of the inside. It goes back to a beginning, emerges on my surface, and it is: East. What is this internal Orient? Nothing exotic. The most intimate part of myself, the ancient restless and tranquil site, where the body felt itself take its first steps. This garment is native; its model: the body’s internal sensation of itself, the secret of the body. Sonia Rykiel designs this sensation. I go to Sonia Rykiel as one goes to a woman, as one goes home. As one goes to a closet-friend; which is to say: I go inside, eyes closed. With my hands, with my eyes in my hands, with my eyes groping like hands, I see—touch the body hidden in the body.

In moving outward, in expressing oneself in wool, in jersey, in visible forms, the intimate does not show itself, does not exhibit itself. There is no rupture with the body hidden in the body. There is continuity. Transmission of the secret, barely perceptible revelation. Everything is continuous. It brims over the edges; the garment doesn’t stop short, doesn’t declare its boundaries, doesn’t gather in its frontiers. The gentle unbordering of fabrics, the terrestrial fabric, takes place in gradual, light changes of color and substance. Skin of the world. And the seams? I mean the inside out, I mean the right side out, I mean the right side where it is the inside out that is the right side. My mother said to me: You put your sweater on inside out again. It’s strange. —It’s Sonia Rykiel. That the seams should remain apparent is the immodesty of writing. Writing likes its composition to be savored. Ever since the Bible, writing is what lets the inside out show: and there is no more inside out.

The nonviolence of these clothes: Sonia’s clothes never turn back against the body, never attack it, never seek to put one in one’s place. They don’t conceal, don’t forbid. There are shield-clothes, mirror-clothes, shimmering, dazzling clothes, clothes which both attract and repel the gaze, clothes of the armor species, clothes which remold the body to a precise measure, to perfect composure, clothes which adorn. I have had some. Few. I never liked them. I donned them to go to war. Sonia’s clothes are for peace. For skin which breathes like animals in the field. Not loving the gaze. They give themselves to be lived. At Sonia’s, as in my home. I enter the tender ancestral tent, and in its peaceful and near shelter, I become friendly, I am her friend and the friend of the world. It is a question of an alliance, a marriage, an accord: of the arch of the feet with the sand, of the flesh with the water. I enter the garment. It is as if I were going into the water. I enter the dress as I enter the water which envelops me and, without effacing me, hides me transparently. And here I am, dressed at the closest point to myself. Almost in myself.

I am going to talk about the dress. The dress by Sonia Rykiel doesn’t surprise me. It comes to me, agrees with me, and me with it, and we resemble one another. Between us is the memory of a nomadic fire. The dress dresses a woman I have never known and who is also me. There is a woman who traverses all women. A woman who exists in all paintings and all countries and all houses; whether she is slight or sumptuous, wide or narrow, she is recognizable by her desire to live, by the impetus which lifts her up, by the grace which moves the monumental body as easily as the minute one. This woman needs all of her body to embrace life, to do things, to take pleasure. Undoubtedly it is she who inspires Sonia Rykiel’s dress. This dress (there is only one of them) is the proof that someone exists who is called woman, joyfully, always has been, and who knows what to do with all of her body in the world. A woman who has no angles. A woman who flows in the world, a woman who does not cut herself off from either the world or herself. By all the pockets of the dress she rejoins the body, she re-creates the circle. A woman with long curves, like a tree, like a river, a woman who doesn’t end, a woman of one slow and continuous movement. A woman who feels herself living translates herself through all women like the course of a river. And the dress takes up and pursues the slow course.

I say: the dress. I call every garment ‘dress’. And I only wear pants and pullovers. Yet I hold myself to this inexactitude: because it is into a ‘dress’ that the two pieces translate themselves, into a single enveloping curve in which the apparently separate pieces of the garment melt together. The water opens up, and closes again. The dress doesn’t separate the inside from the outside, it translates, sheltering. Light enchantment of a metaphor that doesn’t erase its source. Sonia Rykiel fabricates the dream of the body: to freely be of a body with the legs, the belly, the thighs, the arms, with the air of the sea, with space. I said a dress, a single dress. For there is only one of the truth. One dress but full of dresses. A dress which holds innumerable dresses within itself. A musical dress, which gives birth to thousands of notes. A dress which bears a kyrielle or stream of garments in its folds. Magic of the anagram [rykiel—kyrielle]. What is there in some names? A kyrielle of names, of fateful signs, prophecies. There are names which sybillate and play with the ears. The name Sonia Rykiel, I mean her sonorous dress, is Sa Robe, ‘Her Dress,’ full of a range of sounds, signs, of innumerable issue. There are names condensed like dreams: a bouquet of syllables whose opening out sends the hundred sounds bounding back to the cardinal points of the imagination.

What is there in Sonia Rykiel? Qui elle (who she)? You hear the resonance of she who lives, unconscious bearer of a treasure of sounds, of fabrics, of a kyrielle of questions, of dreams, of flashes of foreign languages, of Greek, of Russian, of litanies of linen, of invocations to a Creator—who, it must be said, has showered her with gifts—Kyrie eleison. I listen seriously to messages in translation. And if Stéphane Mallarmé had been named differently, would he everywhere have inscribed his nostalgia for a strange marriage never celebrated? I wonder. And there are dresses like dreams full of history, of known unknown persons. Dresses pregnant with dresses and women. In this way the dress, like the dream, is a voyage. A dress which hides in its folds the great voyage in proximity and intimacy. This dress is a dream of the body, the dream of a voyage of the body within the body, of the child within the mother, of the woman within the woman. That is why one feels good in it. One feels loved. This dress I will call Gradiva. It makes me think of the adorable Gradiva by Jensen, the eternal young woman who, after having resuscitated man from among the stones, and herself from among the ashes, aroused in Freud a text as charming as an adored girl. I call it Gradiva, for like the beautiful young woman in the story, who was dressed in a dress of a thousand folds of river, it contains within itself life in the process of reconstituting itself. And in its name it contains the name of the woman full of being Gradiva, ‘the woman in sum.’ A sum of woman?

SONIA RYKIEL IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Three Chapter 8

̶ Vivienne Westwood’s got that in common with Sonia Rykiel. They’re both self-taught, as it turns out. I’m sure that’s no coincidence.

̶ Are you suggesting their style comes from their lack of schooling?

̶ Indirectly, yes. They abhor perfection. They’re original.

̶ You do like that theme, don’t you? Kahn, Manet, Satie…

̶ I do.

Source : Sonia Rykiel, l’intranquille | France 5 Editions DVD, 2009