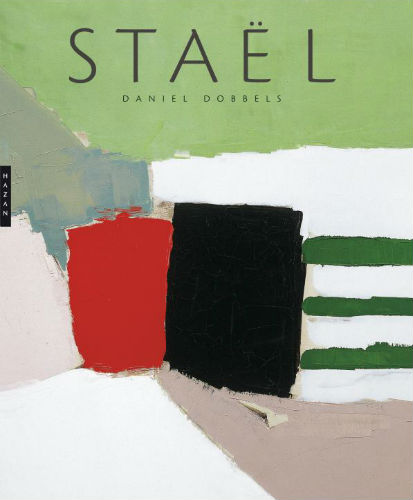

Nicolas de Staël

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Nine Chapter 7

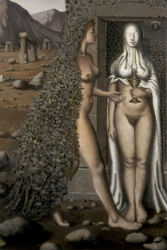

The transformation of awkwardness into grace, the paradox of impetuosity and patience: Waiting in the salon, I study a framed poster of Nicolas de Staël’s Portrait d’Anne. As I configure the colours—ultramarine and crimson, lead white and yellow—into the form of a girl, her decided step, her gangling gait, evoke you. Ingrid is downstairs, on the phone with her agent, while Joost is at his grandparents and you, Klaas and Lia are out skating. As scarlet bleeds into grey-blue, I wonder: Does Ingrid know that as Staël transcended the opposition between figuration and abstraction, he was in the throes of a love affair that would kill him? Does she know, when she contemplates the violence of his palette-knife, that this violence was his means of penetrating to the tenderness underlying his heartbreak? And when she listens to the silence that resonates in his colours, does she have any idea of the vehemence of the feelings that would drive him to his death? Hopelessly in love with another man’s wife, he wrote a letter to Anne, his thirteen-year old daughter, before he threw himself from the tower in Antibes. In vain he’d left his family and implored his beloved to live with him; in vain he’d tried to reconcile wife and mistress. A fury of work—nearly a hundred canvases in a few weeks—brought no salvation. Shortly after he’d left the letter to Anne on a table in his studio, a streetlight picked out his shattered body on the pavement.

Nicolas de Staël, Portrait d’Anne, 1953

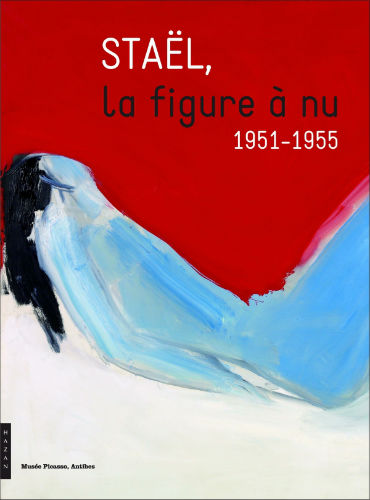

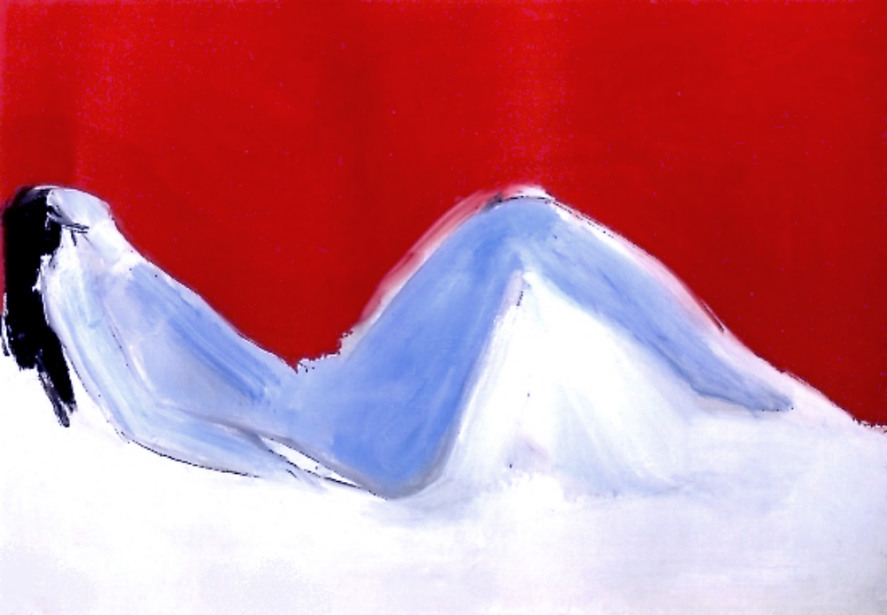

Nicolas de Staël, Nu couché bleu, 1955

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Three Chapter 4

Is she crushed by scarlet, is passion spent, or is she still striving to lose herself in vermilion? Is she opening her legs to cool her loins, or busting her gut to come? Languorous elegance, violent frustration, the blue nude with head thrown back, black hair limp and damp, traces the contours of my confusion: Nicolas de Staël’s Nu couché bleu testifies to the mystery of sex.

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan, Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms – Read the first chapter

HARRY RAND ON NICOLAS DE STAËL

Situating Staël in the Tension between Classical and Modern

Posted by kind permission of Harry Rand

Excerpted from Harry Rand, ‘Raisonné of Nicolas de Staël’ (MIT Press: Leonardo, Vol. 33 No. 1, 2000). The article is available in full from JSTOR.

Harry Rand has published widely on 20th century painting and sculpture and is now Curator at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

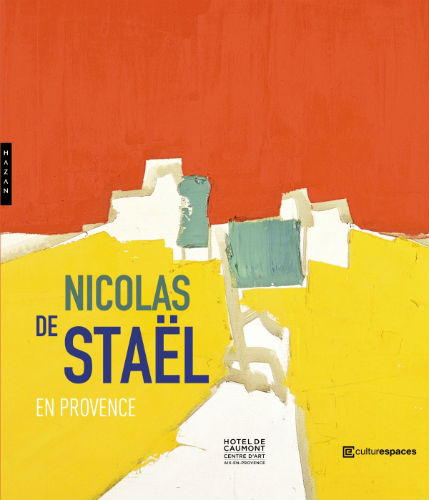

All images are from the exhibition ‘Nicolas de Staël en Provence’ (Aix-en-Provence, 27 April – 23 September 2018)

De Stael’s particular vocation might have been supposed from the evidence of earlier modernism, but no one had dared to live out his exacting response to destiny. The reason is simple: the taxing goals he set for himself lay at the end of a treacherous and precarious journey. There was no guarantee that de Stael would succeed, as the history of modernism is strewn with failed ambitions; these usually are subtracted from the decorous and triumphant narrative. There were aesthetic collapses and losses of nerve just as surely in the arts as in any other field, and often when dealing with the most highly refined sensibilities even the recovery from capitulation seems rewarding.

Nicolas de Staël, Agrigente, 1953

Nicolas de Staël, Sicile, 1954

So, when looking at the often politely gorgeous work of Kees van Dongen we can forget that he was once at the forefront of modernist advance. Likewise, reviewing the history of Cubism it seems impolite to notice that once, at the dawn of this century, Raoul Dufy stood shoulder-to-shoulder with Braque in exploring unknown territory and setting art’s agenda. (What Dufy subsequently created is found sufficiently rewarding that collectors seduced by his blithe subjects never question his apparent cheerfulness; while modernist critics never deign to consider the quotient of art that remains alive in his joyful work—paintings that seem too lighthearted to also be brainy.)

In America—abundantly provincial until the post-war era—frequently insipid iterations of the school of Paris circulated by Stuart Davis and others have been confused with genuine advances of the school of Paris made by a resident American such as Alexander Calder. Only by understanding how modernist failure can be overlooked does it make sense to stress that complete novelty has nothing to do with modernist authenticity; then it is possible to reexamine territory left fallow by past masters.

Nicolas de Staël, Paysage, 1953

Nicolas de Staël, Paysage, 1953

At the heart of de Stael’s relative position in modern history is the myth of secular aesthetic theodicy. According this fable, time sorts out the truly good artists from the heap of the rightfully overlooked. The myth gains its durability not from spectacular examples such as Vincent Van Gogh, where the myth operated more-or-less effectively, but from the basic performance, over generations, by which taste winnows out the products of mere fashion. The spurious personalities—who happen to satisfy a particular critical or aesthetic circle—can be elevated for a time, but with the death of their literary coterie and investors the aura of influence fades, and words like ‘originality’ or ‘genius’ become mannered, then ludicrous.

In the long run, aesthetic theodicy operates in de Stael’s favor so that in a century some of today’s current darlings will be flitting shades in art’s underworld as footnotes, trivia. (Who today can name the sequence of prize winners in the mid-nineteenth-century Paris salons? In a century, today’s Venice Biennale winners will also be mainly curiosities. An inversion will rectify the situation, and that transposition is already in progress.

Nicolas de Staël, Le Soleil, 1953

Nicolas de Staël, Ciel de Vaucluse, 1953

Much of the mid-twentieth century can be understood in relation to de Stael’s career and work. Presently de Stael’s position is correlated to other, apparently fixed stars of art history. Enormous and rightly elevated reputations, such Jackson Pollock’s, will be seen next to their actual accomplishments and then, picture for picture, de Stael’s reputation will hold its own, notable for uncompromising hard vision. He maintained that rigor against the glamour of other more celebrated names and trends, even though he was hardly unknown—which makes his stringency even more biting, as he could not propel himself with the Bohemian bitterness of the loner or misfit.

The price de Stael paid for his self-imposed severity was not the obscurity of an outcast like Van Gogh, the gleeful misrepresentation that the press unleashed on Jackson Pollock, or the self- inflicted personality distortions of Arshile Gorky. Even during de Stael’s lifetime he was a celebrated artist, fashionable almost entirely for the wrong reasons. Viewers were often attracted to suave use of color, magnificent paint handling, thoughtful if not quiescent subjects, and his preservation of European easel painting against the allure of the larger quasi-murals of the Abstract Expressionists.

Nicolas de Staël, Agrigente, 1954

Nicolas de Staël, Marseille, 1954

The antagonism of weighing de Stael against New York is false in the post-war era. De Stael contributed a pictorial organization that extended the dual quality of the surface first essayed by, but hardly exhausted by, Cezanne. Surface could be organized as patterned design and also as a record of perceived depth and volume—with the material of paint operating in both realms simultaneously. How unfashionable this challenge seemed for a modernist artist: to go backward, to reclaim territory already covered but not fully exploited. For de Stael to recover this approach to painting risked appearing reactionary and suited for public lashing, i.e. critical censure in comparison with contemporary explorations.

A similar burden was also shouldered by Giorgio Morandi in Italy and by Jochen Seidel in Germany. The early New York school itself recapitulated a painting technique that was the hallmark of European academics, while Impressionism (and then Cubism) treated representation in a very different manner. The vitality of tradition, and a colloquy with art’s legacy in a really dialectical form, was part of what de Stael made visible to his spectators. In this he was the last, though not the last possible, scion of a long chain of artistic bequests.

Nicolas de Staël, Arbre rouge, 1953

Nicolas de Staël, Grignan, 1953

From Braque, de Stael lovingly wrested the treatment of contrasting colored shapes upon surface, an inheritance that Braque had instantly commandeered when he encountered it in early Matisse. That relationship of animated shape to field Matisse had learned from his teacher, the wildly misunderstood Gustave Moreau (who, recognizing his anomalous situation, sequestered much of his art, withdrawing many pieces from view for a generation—which proved to be a successful gamble).

Moreau, in turn, had inherited this notion from the apostate Chasseriau, who heretically leapt from the camp of Ingres to Delacroix. Ultimately, Ingres, whose figures seemed pasted into their backgrounds, gleaned this object-field relationship from his teacher, Jacques Louis David (who evolved from a young Rococo painter to the first important Neo-Classicist); David absorbed the lessons of his mentor, Joseph-Marie Vien, whose career was deflected by viewing reproductions of Pompeian wall frescos. The ancestry of de Stael’s neo-classical relationship of flat figures to ground will be readily apparent to even a novice who glimpses David’s Count Potocki (1781) and then views a first-century Roman mural.

Nicolas de Staël, Arbres et maisons, 1953

Nicolas de Staël, Les Martigues, 1954

Just so long-lived was this urge to systematically array a depiction of the world, to give regularity to sight. David’s Count Potocki—upon his horse, saluting the viewer with a sheer stone wall rising at his back—situates a point halfway between ancient Rome and de Stael’s still lifes and nautical scenes, their subjects with sheer walls of color rising behind them. Rather than unnatural rigidity, this tradition—or craving, to order the world in a regular way—underlies grammar, theology and science. (Each share a sense that a few regulatory mechanisms—a set of limiting rules—governs the world.)

Sometimes the values of harmony and simplicity have come under attack in the last century because of their apparently anti-democratic implications; the wildly unpredictable masses are not tidy, and democracy requires a deep trust in irregularity and unpredictability. Yet not every implication espied must be enacted, and aesthetic choices should not be suppressed any more than scientific experiments—all must be open to examination, nuclear fission or Surrealism—without necessarily wholesale implementation of the experimental results.

Nicolas de Staël, Agrigente, 1953-54

Nicolas de Staël, Paysage de Sicile, 1953

Accordingly, Neo-Classicism prefers the regular to the erratic, the predictable to the random, sustainable lyricism to the momentary entertainment of fright, and so forth. The straining hyper-critical intelligence of an artist of the caliber of de Stael had to overpower the tension between the Classical and the implications of the modern. That strain is visible in every one of his best canvases—which is to say, most of his later pictures—just so high was de Stael’s batting average, so unceasing was de Stael’s tribulation.