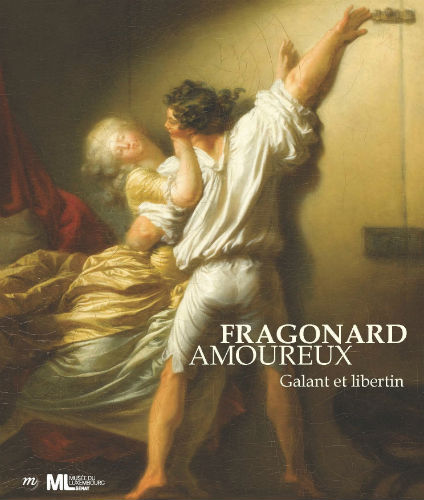

Fragonard

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Four Chapter 4

Fragonard’s Swing

Will he remember, when he’s old and grey,

How his heart would flutter to the sway of her swing?

Will she remember, when she’s past her day,

The kindling power of her petticoats?

Hearts like bells, celebrate the living

Mourn the dead, break the lightning

Toothless and dribbling, will he still recall

The arch of her instep, the sandal, the fall?

Her poise at the still-point between surrender and retreat,

Eyeless and infirm, will it still taste sweet?

Hearts like bells, celebrate the living

Mourn the dead, break the lightning

The thrill of expectation, the sudden glimpse—

Will they reminisce about their frivolity?

Will they be convinced by the instant’s eloquence

That to transience the flower owes its beauty?

Hearts like bells, celebrate the living

Mourn the dead, break the lightning

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Swing (Les Hasards heureux de l’escarpolette), 1767

EWA LAJER-BURCHARTH ON FRAGONARD

Eros and Individuality

Posted by kind permission of Ewa Lajer-Burcharth

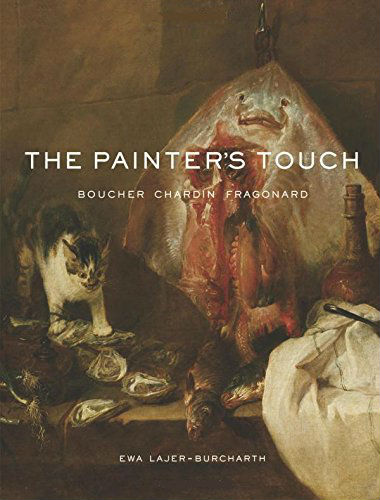

From Ewa Lajer-Burcharth, The Painter’s Touch: Boucher, Chardin, Fragonard (Princeton University Press, 2018) | Ewa Lajer-Burcharth is Professor of Fine Arts at Harvard University.

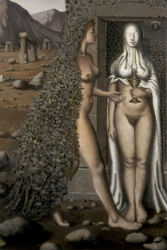

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Stolen Shift, c.1765

To achieve happiness, everyone has to grasp the type of pleasure that is proper to him.

Thérèse philosophe

Rather than taking Fragonard for granted as a belated artist caught up with the waning aristocratic ethos of libertinage, or, alternately, as a mis-recognized proto-romantic painter of passion—which is how his project has most often been construed—it seems more fruitful to consider the painter’s entire erotic oeuvre as a symptom of the pressing cultural need to figure out the relation between sex and self.

The question is, how did Fragonard’s work, as painting, address this new need, and how exactly, in this capacity, did it contribute to the period’s discourse of sexual pleasure? If modernity is indeed a cultural formation that insists on sex as the truth of self, what are the truths—and the self—that Fragonard articulated?

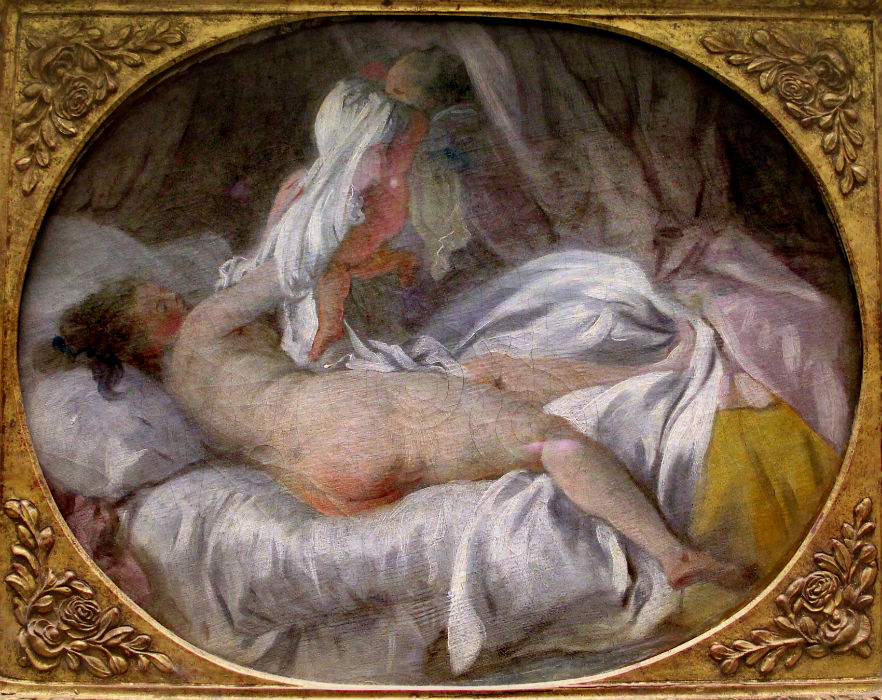

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, All Ablaze, c.1765

François Boucher, Pastoral with a Couple near a Fountain, 1749 (detail)

We may begin, in art-historical terms, by asking about the position Fragonard occupied in relation to other eighteenth-century painters of sexual themes. Where does his work stand in relation to his teacher, Boucher?

Although in the beginning of his career Fragonard followed Boucher closely—as his early The Seesaw demonstrates—he came to develop an entirely different approach to eros, both in the character of the represented scenes and in their pictorial rendition. Put briefly, Fragonard’s oeuvre formulates a new sexual imaginary in which erotic experience is redefined in individualized, privatized, and thoroughly physical terms.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Seesaw, c.1750-52

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Bolt, 1778

Most obviously, Fragonard’s licentious scenarios tend to feature contemporary rather than the mythological figures or pastoral characters that prevailed in Boucher’s repertory. Moreover, Fragonard’s figures tend to be anonymous individuals as opposed to socially situated actors. It is relatively difficult to pin down their class insofar as the markers of social status are inconspicuous, inconsistent, and ultimately unconvincing. For example, if the identity of the ravished woman swathed in yellow satin in The Bolt is unmistakably upper class, the social standing of her partner remains uncertain.

In the Happy Lovers no social identification of any kind is possible: all one can say is that these are two bodies engaged in making love. One may also note that the individuation of these figures is kept to a minimum: their physiognomies are conventional and summarily rendered—a dot for the eye, a crescent for the mouth—just enough articulation to suggest the movement of emotion or desire across the face, without implying character or personality. It is as the generic man and woman that these individuals wrestle in amorous combats. Subjects of desire rather than social class, their rapport is defined by remarkable reciprocity.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Happy Lovers, c.1770

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Servant Girls’ Dormitory, 1770

Furthermore, one is struck by the heightened intimacy of Fragonard’s scenes staged, prevalently, in interiors. In bolted rooms, on unmade beds, under the shade of a canopy, sexual activity—be it an interaction between two people or an autoerotic performance—is repeatedly defined in Fragonard’s paintings as a guardedly private act. The voyeuristic position that these images tend to accord the viewer only emphasizes the privatized character of these scenes. Fragonard’s work evidently contributed to the important cultural change that occurred in the course of the eighteenth century when sex came to be understood as an activity apart, an experience that requires privacy. The bolt has clicked, the couple has been locked in a room where no one else, except our gaze, can enter, and the new cultural location of desire as a discrete space—a spatial secret—came visually into being.

Notable also is that while Fragonard works essentially within a genre format, traditionally used for gallant scenes, he shifts its usual emphasis. It is not the elaborate social rituals of seduction that he represents, as did earlier Antoine Watteau or Jean-Francois de Troy, but an intimate physical engagement, the dynamics of sex as bodily motion, as friction between material surfaces. One may also note that far more nudity appears in Fragonard’s pictures compared to the work of his predecessors, helping define the notion of direct physical contact between bodies as a key aspect of the erotic encounter.

Fragonard, Alcine and Roger in His Bedroom, c.1780

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Useless Resistance, c.1770-73

Even such a cursory overview makes clear that Fragonard did not simply paint sex but sketched out the contours of a historically specific argument about it that may be roughly defined as materialist, in the eighteenth-century sense of the word. His very emphasis on the physical dimension of sex suggests a materialist understanding of desire as a physiologically specific force of attraction between bodies rather than souls.

It is precisely in these physiologically specific terms that Diderot, in the Encyclopédie, defined the idea of sexual pleasure as a natural bodily phenomenon: ‘An individual presents himself to another individual of the same species and of different sex, the feeling of any other need is suspended; the heart palpitates, the limbs quiver; the voluptuous images wander in the brain; the torrents of energy run through the nerves, irritate them, before surrendering under the siege of a new sensation, insistent and tormenting. The sight becomes blurred, the delirium is born; reason, the slave of instinct, limits itself to serving it, and nature is satisfied’.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Bathers, 1763-64

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Kiss, c.1770 (detail)

This passage could almost serve as a caption for the Happy Lovers, their bodies painted as if they were indeed animated by some internal torrent of energy, their cheeks flushed with rushing blood, their embracing limbs melting into each other while the couple, oblivious to the world surrounding them, engages in their natural pursuit. Or take The Kiss, a small oil sketch rendered in whorls and smudges of pigment, where the upper torsos of the lovers seem to have sunk into each other with a force of suction so strong that you can almost hear it—here, too, sexual encounter is constructed in terms of sheer physical energy.

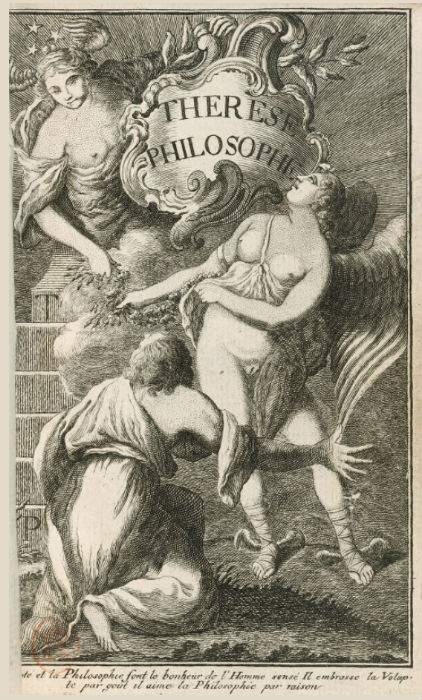

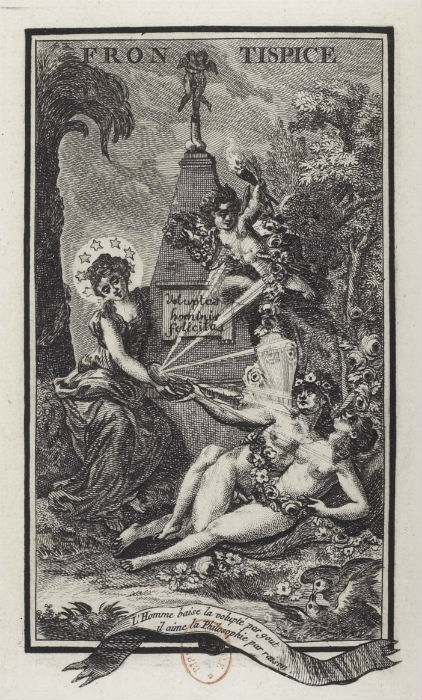

I am not suggesting that the Encyclopédie or the materialist philosophy of the body were the direct sources of Fragonard paintings, but rather that his aesthetic project might be situated within a larger cultural field of inquiry into sexuality as a basic human activity in need of reappraisal. That the meaning of sexual experience must be re-evaluated was, for example, the main message of pornographic literature, which in this period became an important tool for disseminating philosophical materialism. Explicit descriptions of sexual acts were often interspersed in these publications with sophisticated expositions of materialist philosophy, the task of arousal mingled with the didactic purpose of ‘naturalizing’ eros. Thus the single most popular eighteenth-century pornographic novel, Thérèse philosophe, first published in 1748, offered an account of sexuality that echoed the arguments of such Enlightenment writers as Julien Offray de La Mettrie and Diderot (so much so that the latter was even believed to be its author).

Thérèse philosophe, 1748

Thérèse philosophe, 1748

The sexual vicissitudes of a young woman were presented as a pursuit of pleasure following the implacable laws of nature, a human body understood, in La Mettrie’s terms, as a machine à jouir (machine for enjoyment). The main emphasis of the novel was, though, on the individual—and individuating—dimension of sex. As one of its protagonists put it succinctly: ‘To achieve happiness, everyone has to grasp the kind of pleasure that is proper to him.’ Thérèse’s erotic adventures were to be understood not as mere diversions but as a pursuit of her erotic truth, her own unique kind of sexual satisfaction. Fragonard’s paintings share with Thérèse philosophe this materialist emphasis on the individuality of sexual experience, and such illustrated pornographic novels may well have served as the mediating factor between philosophical materialism and Fragonard’s vision.

FRONTISPIECE LEGEND:

L’Homme baise la volupté par goût; il aime la Philosophie par raison.

Man embraces voluptuousness out of fancy; he loves Philosophy out of reason.

THÉRÈSE PHILOSOPHE: FOUR IMAGES

Images courtesy of the Bibliothèque nationale de France

Thérèse philosophe, 1748

Thérèse philosophe, 1748

Thérèse philosophe, 1748

Thérèse philosophe, 1748

Ewa Lajer-Burcharth, The Painter’s Touch

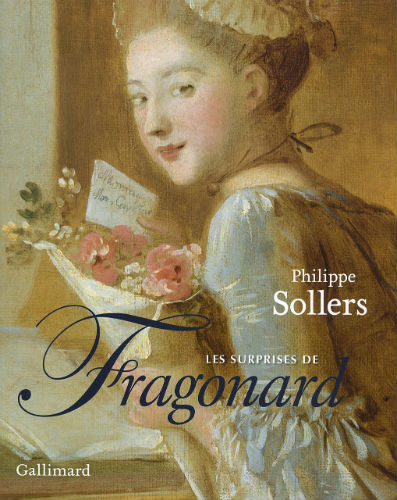

Philippe Sollers, Les Surprises de Fragonard

OF DOGS AND GIRLS: FRAGONARD’S WIT

Patricia Simons, ‘Puppy Love: Fragonard’s Dogs and Donuts’

Excerpts from the article published in Notes in the History of Art, Vol. 34, No. 3 (Spring 2015), pp. 17-24. The full paper is available from JSTOR.

The king’s last mistress, Madame du Barry (1743-1793), was a renowned courtesan whose licentious story was the gossipy point of the best-selling Anecdotes sur Mme la comtesse du Barry, first published in 1775. According to her false autobiography, penned by Baron Étienne-Léon de Lamothe-Langon and printed in 1829, she was exceptionally fond of a small dog similar to the one depicted here. This spoiled Dorine was ‘pretty, affectionate, attached to her mistress, much admired for her vivacity, lightness and grace, long tail ending in a tuft, and especially her snow-white coat.’ One of many rumors about du Barry, the nature of her étrange distraction is unspecified, but the innuendo is clearly lewd.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, La Gimblette, c.1770

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Two Girls on a Bed Playing with their Dogs, n.d.

What might at first appear to be a charming scene of pubescent playfulness contains what would have been familiar sexual word play, visual puns, and saucy inferences regarding court gossip. The obscene nature of the gimblette scenario was recognized in the eighteenth century.

Through a series of puns, displacements, and gestures, Fragonard exuberantly demonstrates that all the artist allows us to see is sensual surface.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, La Gimblette, n.d.

IS THIS A FRAGONARD PHOTO?

Morena Fortino, La Chatte

I’d say so. It’s by a woman affirming herself.

R.J.