Egon Schiele

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Intermezzo 1: Lilo

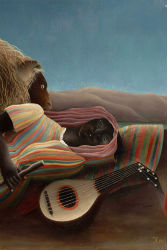

Downstairs, the floors, ceilings and walls are white: Lilo makes the most of the Northern light. The kitchen extends across the whole width of the house. At one end, an island unit holds the hob and a breakfast bar; at the other, a work desk serves as a dining table. Look! Burnt-down candles in candlesticks; a vase, fresh flowers. In the living room, their backs to the window, two steel-framed wicker chairs stand discreet and elegant. Edith, Egon Schiele’s wife, beautifully drawn in three crouching nudes in the last year of the artist’s life, occupies one wall. The others are bare. In the middle of the room, a round table on a textured rug gives off a black sheen. I’m sitting in an Egg chair, my feet on the ottoman. Lilo’s sitting lotus-like on the sofa. We’ve just had lunch (Braunkohl und Pinkel), after a morning spent at the Paula Modersohn-Becker Museum.

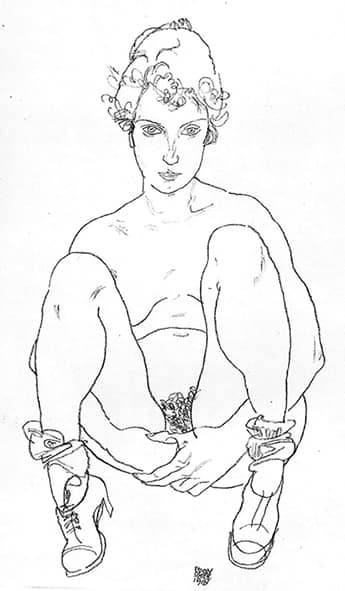

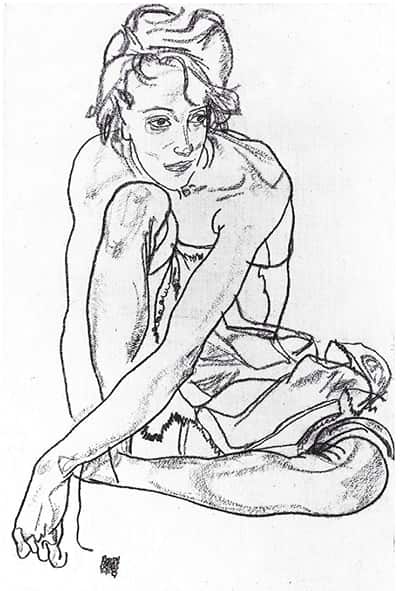

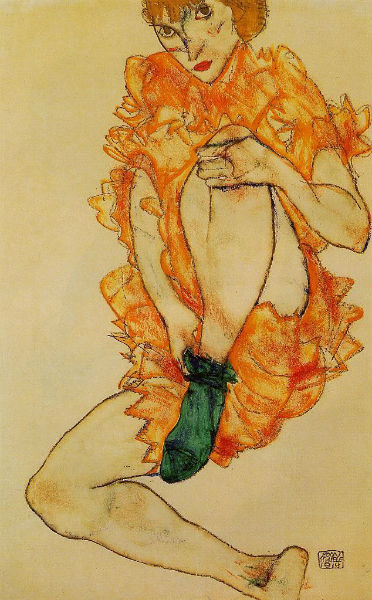

Egon Schiele, Crouching Nude, 1918

Egon Schiele, Crouching Nude, 1918

We speak of women artists, we find we share a love for Frida Kahlo, Tamara de Lempicka, Remedios Varo. We speak of Egon Schiele, dead at twenty-eight. Lilo says she likes the drawings on her wall, but she prefers Egon’s earlier work. I agree that Edith’s too old to be a girl like Rimbaud (my first gift to Lilo) but not Gerti, Wally and the working-class girls. I explain why I’m so moved by Edith: If she didn’t have Wally’s divine gift of lust, she did show Egon that to be moving he didn’t have to be demonic.

̶ Sprague, you’re so isolated in that Egg chair. Come here. Come and sit next to me.

I go and sit next to her. She unfolds the throw she’d wrapped around herself and gives me one end of it; I pull it till it covers me from the neck down.

We sat like that, wrapped in one blanket, for the longest while. Yes, in the fading Northern light we sat in intimate silence, Lilo and I, as if we’d been lovers for a long time.

Egon Schiele, Crouching Nude, 1918

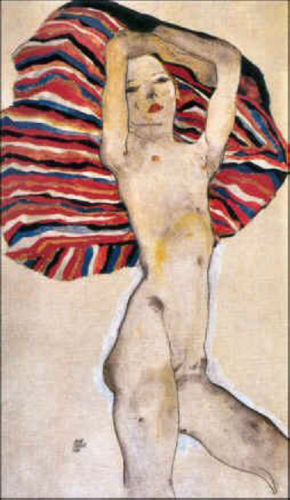

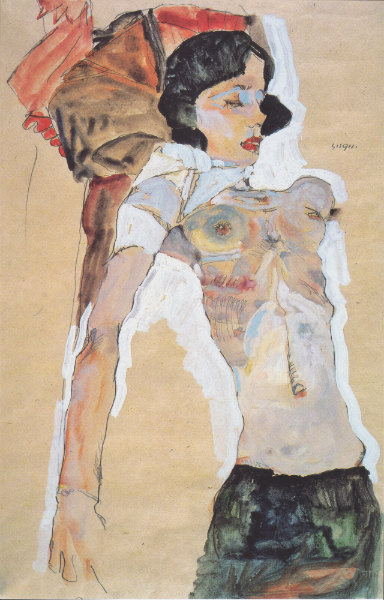

Egon Schiele, Nude against Coloured Fabric, 1911

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Five Chapter 1

Still I speculate, still I ponder: When you surprised yourself in the mirror, when you became a stranger to yourself, who was the who you dreamt yourself to be?

̶ Mirror, mirror, tell no lies, how do I look in Egon Schiele’s eyes?

̶ Gaunt, stark, raw in her nakedness, the girl you once were confronts you. Instantly you recognize her defiant vulnerability and self-subjugation, her vestigial femininity and proud isolation. A wave of tenderness overwhelms you, you feel a kind of homecoming: Never have you forgotten this girl who lives inside you, never has a day gone by without you paying her tribute.

EGON SCHIELE, PAINTER OF ADOLESCENCE

THE VIOLENCE OF LIFE IMPRISONED IN THE BODY

By Alex Lefèbvre

Posted by kind permission of Alex Lefèbvre, Emeritus Professor in Clinical Psychology at the Université Libre de Bruxelles.

From Alex Lefèbvre, « Egon Schiele, vie et mort du corps pulsé », in Anne Brun et al., Cliniques de la création, De Boeck Supérieur « Oxalis », 2007, p. 105-115.

These passages translated by Richard Jonathan.

The two quotations below, from Schiele’s prison diary, are my addition, not part of the article.

‘I believe that man must suffer from sexual torture as long as he is capable of sexual feelings.’

Egon Schiele, Prison Diary. Cited in Frank Whitford, Egon Schiele (London: Thames and Hudson, 1981) p.119

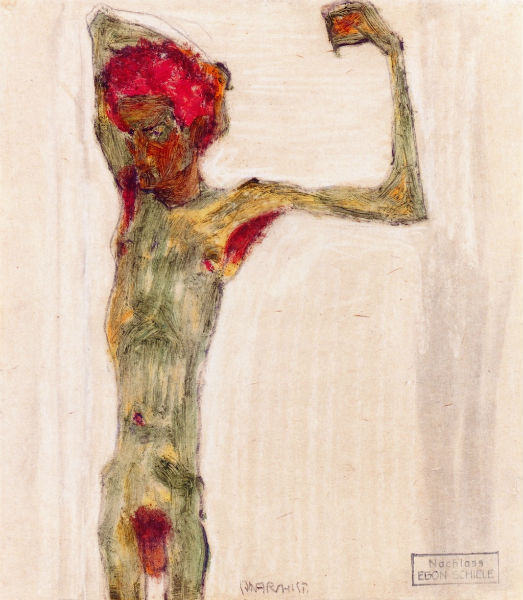

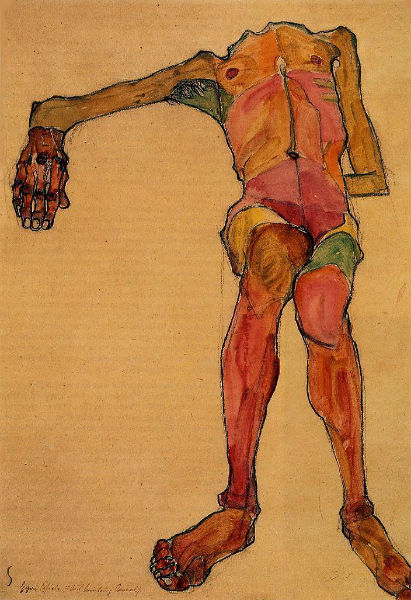

Egon Schiele, Anarchist, 1910

Egon Schiele, The Green Stocking, 1914

‘No erotic work of art is filth if it is artistically significant; it is only turned into filth if the beholder is filthy.’

Egon Schiele, Prison Diary. Cited in Frank Whitford, Egon Schiele (London: Thames and Hudson, 1981) p.119

Analyzing the frescoes of Pompeii and their theme of sexual intercourse and its representation, Pascal Quignard, in his book Le sexe et l’effroi, foregrounds the fact that human beings are beings of desire who seek in every object and every activity, everything they make and everything they create, an image of what they cannot see: that primal scene at which they were not present, that scene that makes of man ‘a desiring gaze that seeks something else behind everything he sees’.

The fascination that Schiele’s nudes exert relates to his image vis-à-vis both his models and himself. Forthright and frank, his drawing attempts to capture the contours of this unrepresentable something, this subliminal something, this something that sustains the origin but cannot represent it. Schiele’s hand attempts to pin down what his desiring gaze is casting around for behind the apparent. His line explores the contours of the world projected into the corporeal space that it encounters, that it sounds, that it passes through, and whose enigma it tries unceasingly to decipher.

Egon Schiele, Lovemaking, 1915

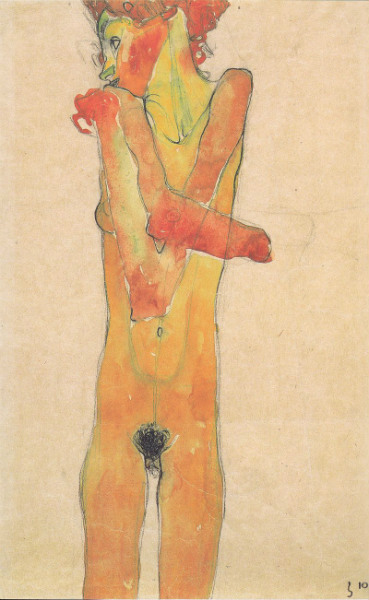

Egon Schiele, Naked Girl with Crossed Arms, 1910

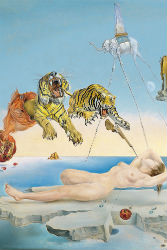

Take, for instance, his watercolours of barely pubescent girls, like that of his sister Gertrude (Nude Girl with Crossed Arms, 1910). Her naked body presents itself to be captured by her brother in a form of original innocence, on the borderline of ecstasy and incest, as if, in the candour of her own pubescent discovery, she cleaves with all her desire to the will of her brother.

Other pubescent bodies will follow, then more nubile ones, and they will offer Egon unrestrained incarnations of the fantasized forms of his desires. These drawings do not plunge us into the physical intimacy of the models; instead, they violently return us to Egon’s drive-driven gaze, a gaze in which we perceive the expressive staging of an interior drama shaken up by the tensions of his psychic life, a life whose nature they then further activate. The beauty of the forms assertively drawn on the paper, with no corrections, always from nature, the colours coming after, from memory, without the model, like a return, like an emotional replay, propel us into the site of creation itself. We find ourselves present at the very heart of what is coming into being.

Egon Schiele, Woman with Green Turban, 1914

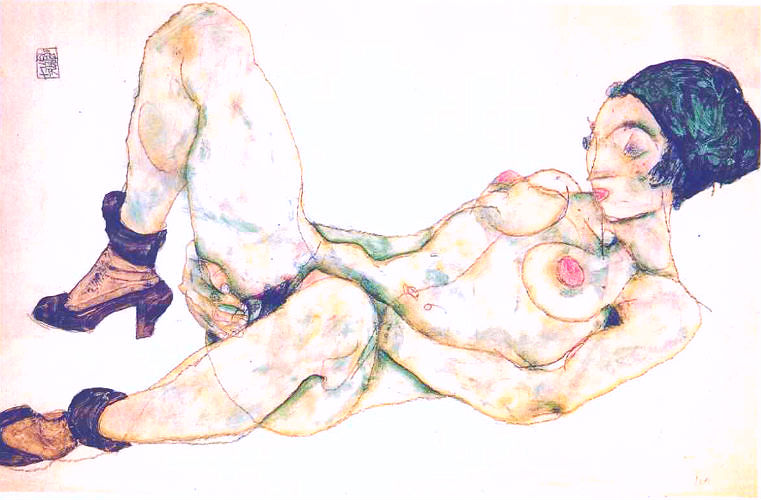

Egon Schiele, Reclining Nude, 1917

Desire projects itself into the flesh of his sister and then other sisters whose naked bodies, unrestrained, will be fashioned by the line of the painter’s gaze. Gerthi, Wally, Edith and all those barely pubescent girls will file through Egon’s workshop and strike poses the artist has deliberately staged, as in a game, in a quest for life. The bodies are twisted, under extreme tension. The work begins with the painter ‘sculpting’ the model’s body, projecting onto her his internal tension via the pose he ‘inflicts’ on her, preparatory to capturing it in drawing. The models are exhibited, offered up and handed over to his clinical gaze, beyond any taboo, pushing to extremes contortion and the obscene.

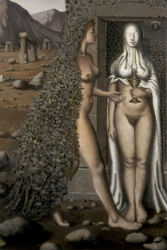

Whatever the changes in Egon’s thematic interests (they would broaden to include the more cultural subjects of the period), unchanging is this trace—primitive, primeval, profoundly original—of the line that tirelessly throws into question, in evident pain, what underlies appearances, repressed psychic tensions, the underpinnings of a set of phantasies driven by the mysteries of the sexual. We do not see Egon’s paintings and drawings: it is they that see us. They force us to confront ourselves; endlessly they suck us into an abyss of subjectivity. They induce a loss of signification, for sensuality is in excess; they induce a loss of the other, for the other’s absence is in excess; they induce, finally, the loss of oneself.

Egon Schiele, Redhead Girl with Open Legs, 1910

Egon Schiele, Half-Undressed Girl, 1911

Schiele’s way of working: First, the encounter with the model, the capture of an interior trace not yet intelligible that the artist will first ‘sculpt’, via her pose, ‘onto’ the model (the medium of the ‘sculpture’ being her body), even if this entails mistreating her. The aim: to bring to the surface of the skin the tensions caused by this drive-driven demand. A strange dance, then, of the painter around his model, a dance in which his probing gaze relentlessly searches for an angle of attack, of penetration, and goes so far as to seek a final unveiling of the nudity already before him.

In this encounter with these girls’ bodies, there is as it were a putting into place of ‘affective mirrors’, of empathy and compassion, that favours what Winnicott called ‘the ability to be alone in the presence of the object’. Schiele’s quasi-compulsion to draw recalls those solitary games under the gaze of the other, the auto-subjective game that consists in giving oneself a pleasure, a pleasure previously received from the object, appropriating a capacity previously provided by the object, a game always experienced as a way to take back from the object this pleasure, this capacity. His painting conveys to us a mise-en-abyme of this situation, eliciting from our perception that same auto-subjective activity beholden to the game of mirrored gazes, of the nudity of the world and its origins, of a few details of bodies over-cathected like sensory fetishes of a partial sexualization. Between the pure game of the reflexive mirror and the engagement of this auto-subjective game, there is all the assurance of that symbolizing instrument that is Schiele’s gift of drawing, of that intermediate instrumental function that opens up to both oneself and the other.

Egon Schiele, Seated Woman with Bent Knee, 1917

Egon Schiele, Seated Male Nude, 1910

Egon Schiele was perhaps a damned painter, disposed to being burned at the stake of a century and an empire coming to a close, but he was also and especially a painter of imperious necessity and freedom, of searing intensity and disruption. The creative rage with which he expressed the violence of life imprisoned in the body represents an innovative and cathartic movement of this period in Vienna, a movement aimed at throwing off the shackles of a prescriptive morality, a morality locked in the illusion of eternity.

Egon is the painter of adolescence, leaving a world where nothing is possible any longer in order to open up a future where all is possible, be it death itself. In this, he echoes Rimbaud’s cry: ‘Let the moment come / when hearts will be one’.

For the Rimbaud poem in full, see RIMBAUD I, Chanson de la plus haute tour | Song from the Tallest Tower.

A. Brun & J-M Talpin, Cliniques de la Création

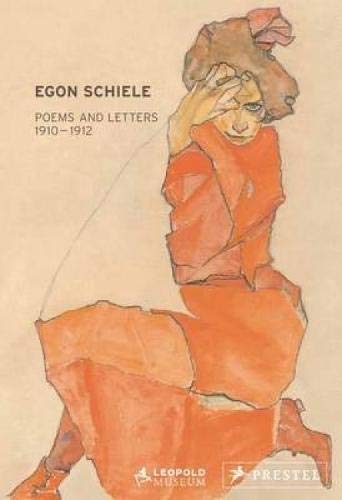

Frank Whitford, Egon Schiele

Egon Schiele: Poems and Letters 1910-1912