Hieronymus Bosch

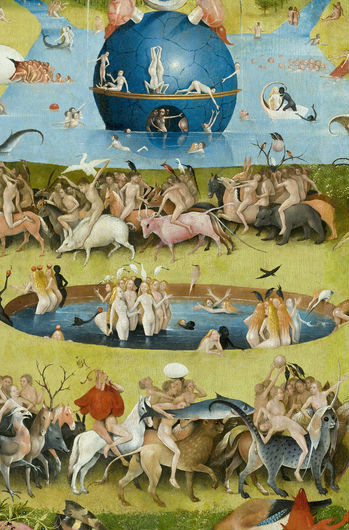

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1490–1500

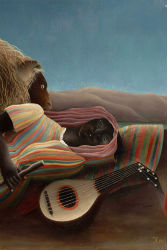

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Eight Chapter 2

A slow upbow of the second violin fills the hall with pent-up power, and then the ensemble feeds the ferocity of Shostakovich’s rage: A percussive attack of monolithic chords underpins a frenzied melodic line.

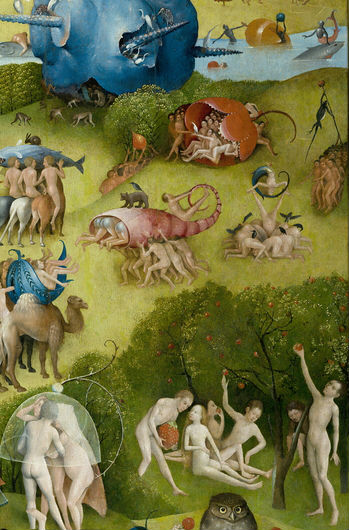

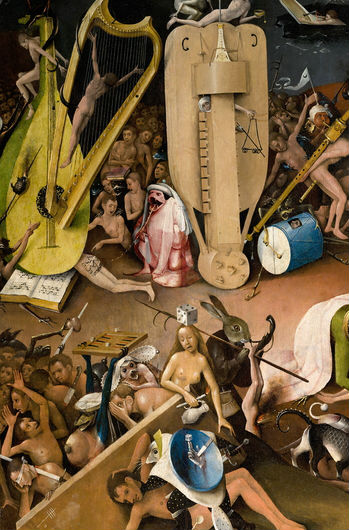

Hieronymus Bosch, Garden of Earthly Delights (detail)

Hieronymus Bosch, Garden of Earthly Delights (detail)

Onward it drives, inexorable, in a headlong rush to—nowhere. I’ve felt it myself, that futile rage. The horrible, impossible news, that morning in Rovinj. Reminisce, dizziness, loneliness! The relentless fortissimo of the dactylic rhythm drives you deeper into yourself.

Daddy, your memories drowned when you did, but look how mine have a hold on me: Over ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’ I glide my magnifying glass, delighting in the little creatures, making the monsters the heroes of the stories we’d invent.

Hieronymus Bosch, Garden of Earthly Delights (detail)

WALTER S. GIBSON ON HIERONYMUS BOSCH

Style and Artistic Heritage

From Walter S. Gibson, Hieronymus Bosch (London: Thames and Hudson, 1973)

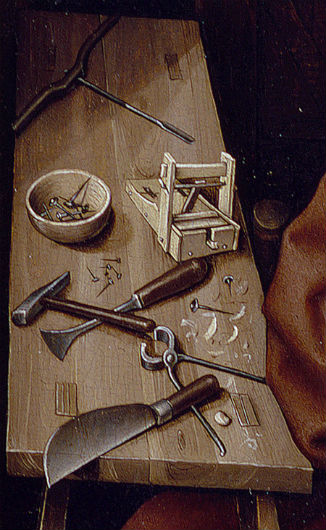

Hieronymus Bosch, Death and the Miser, c.1494

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Hieronymus Bosch, Gluttony and Lust, 1490-1500

Yale University Art Gallery

Bosch’s early works constitute a relatively homogeneous group, reflecting the style of the fifteenth-century Dutch illuminators and panel-painters. Yet even in these works innovations can be found which anticipate his later paintings. A transition to his middle period (c.1485–1500) is provided by three stylistically related panels, the Ship of Fools, the Yale Gluttony and Lust and the Death of the Miser. Although these subjects were new to panel-painting of the period, the rather prosaic devils in the Death of the Miser are not much advanced over those in the Hell scene of the Prado Tabletop, whose original design must reflect Bosch’s earliest style. The Brussels Christ on the Cross should perhaps also be assigned to this transitional group.

At the heart of the middle period undoubtedly lie the Vienna Last Judgment and the Haywain triptych. Bosch’s inventive genius first blossomed in the Last Judgment. Its apocalyptic character is distinctly original, while the proliferation of devils and torments is without precedent in earlier Netherlandish painting. Yet it would seem that this new richness of iconography overwhelmed the artist’s sense of order: infernal giants and structures are piled one upon the other somewhat incoherently in the right wing with little regard for spatial recession, and myriad forms are scattered rather aimlessly across the central panel. Much more carefully composed is the Hell panel of the Haywain triptych, whose details are subordinated to the tower under construction. In the Eden wing we see, probably for the first time, those exotic vegetable and mineral forms which were to dominate the landscape of the Garden of Earthly Delights.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Last Judgement, c. 1506

Gemäldegalerie der Akademie der bildenden Künste, Vienna

Hieronymus Bosch, St. Christopher Carrying the Christ Child, c.1495

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

Other paintings of the middle period include perhaps the St Christopher and the two small altar wings, both in Rotterdam, the Berlin St John on Patmos, and possibly also the Hermit Saints triptych, whose St Anthony wing anticipates the right panel of the Lisbon triptych, as well as the relatively traditional Christ Carrying the Cross in Madrid.

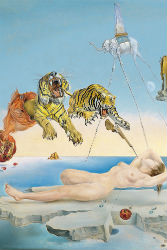

The third phase, which probably began after 1500, marks the climax of Bosch’s art. This is the period distinguished by the Garden of Earthly Delights, the Lisbon St Anthony and the Prado Epiphany, in which even more brilliant innovations are accompanied by a greater clarity of composition.

Hieronymus Bosch, Triptych of the Temptation of St. Anthony, c.1500

Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon

Hieronymus Bosch, Garden of Earthly Delights (detail)

The swarm of nudes in the Garden of Earthly Delights is organized into rhythmically interlocking groups; the adjacent Hell panel is divided into three distinct zones that lead the eye back into the flaming darkness, while the multitude of forms is subordinated to the brooding figure of the Tree-Man in the centre.

The Garden of Earthly Delights contains Bosch’s most bizarre Hell scene; but the nightmare-like fluctuations of the demon world are even more successfully evoked in the central panel of the Lisbon St Anthony, which displays the same mastery of composition. The demons attacking St Anthony are organized around the ruined chapel and its landing stage, while the diagonals of the gallery and wall flanking the chapel are echoed in the side panels: in the bridge and path on the left and in the rock on which Anthony sits on the right.

Hieronymus Bosch, Temptation of St. Anthony, c.1500 (central panel, detail)

Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon

Hieronymus Bosch, Adoration of the Magi (Epiphany), c.1485-1500 (inner panels)

Museo del Prado, Madrid

The inner panels of the Prado Epiphany are united by the broad panoramic landscape in the background and by the repetition of blue and red among the foreground figures. Like the early Marriage Feast at Cana, the Epiphany scene and the Mass of St Gregory on the reverse clearly reveal how freely Bosch could treat even the most traditional Christian subjects.

Artists before Bosch seldom succeeded in translating the images of the medieval writers into vivid concrete form; their scenes of Hell, for example, never quite convey the horror experienced by Tundale and Lazarus. If Bosch was able to realize his vision of the afterlife with such frightening intensity, it was because, paradoxically, he brought to them a style of painting which had been developed for the scrupulous depiction of the life here and now. His monsters are as convincingly real, as circumstantially detailed, as the brass ewers of Campin and Van der Weyden and the vase of flowers which appears in the Portinari altarpiece of Hugo van der Goes.

Robert Campin, The Annunciation Triptych, c.1427 (detail)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC

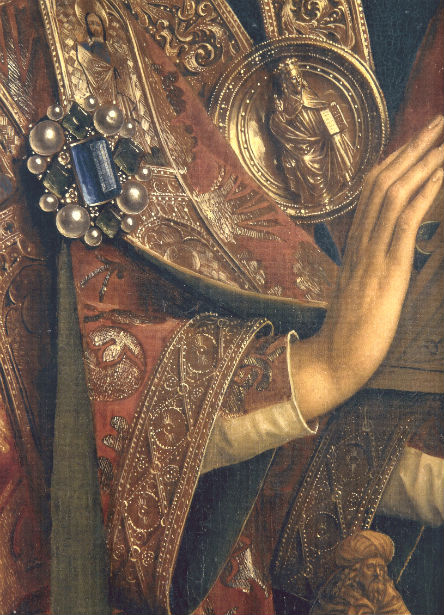

Jan van Eyck, Ghent Altarpiece, 1425-32 (detail)

St Bavo’s Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium

But while Bosch inherited much from the earlier Netherlandish painters, his pictures do not display their meticulous technique, their carefully built-up layers of oil glazes which give such a jewel-like brilliance to the Ghent altarpiece, for instance, or Memling’s Madonnas. On the contrary, his fantastic forms must have grown fairly rapidly beneath his brush, ‘all in one process’, as Van Mander aptly describes it.

As his better-preserved works show, the brushwork is loose and fluid, the paint often applied so thinly upon the surface that the black chalk underdrawing is visible beneath. In some instances we can observe changes which Bosch made in his composition. In the Death of the Miser, for example, the arrow held by Death was shortened in the final version. In the Mocking of Christ in London, the hands of Christ were altered in position, which explains the somewhat awkward gesture of the man at lower left.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Mocking of Christ, c.1510

National Gallery, London

Bosch, Triptych of the Temptation of St. Anthony, c.1500 (detail)

Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon

Bosch employed a wide gamut of colours; rose and blue dominate some of his earlier works, echoing a practice among the Utrecht illuminators, while his later paintings show stronger contrasts of red and green or orange and purple. The better-preserved works show how he characteristically modulated his solid areas of colour with other hues: greys are warmed by green and lavender, white enhanced by blue and pink, yellow with red. This subtle handling of colour can clearly be seen in the figure of the demon priest in the Lisbon St Anthony [lower-right corner]. His green cloak is shot through with red and yellow and a darker green; browns and ochres model the basic flesh tones of the head.

Bosch’s richly variegated colours are further enlivened by his highlights. Little flecks of light glitter on the rigging of the boat and on the skirt of the fool in the Ship of Fools, sparkle like dewdrops on the fruits of evil that spring up among the desert saints, and gleam on the headdresses and ornaments of the Magi in the Prado Epiphany.

Hieronymus Bosch, Ship of Fools, 1490–1500

Musée du Louvre, Paris

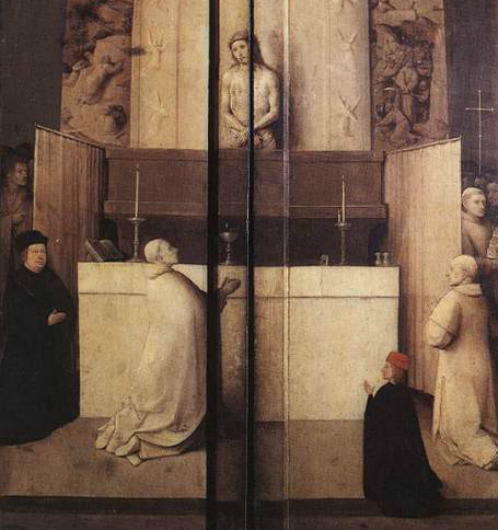

Hieronymus Bosch, Mass of St. Gregory

Outer wings of Adoration of the Magi (Epiphany), c.1485-1500

Museo del Prado, Madrid

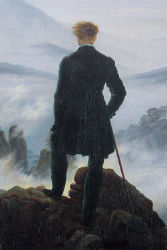

Whereas the Flemish artists tended to see in terms of line and volume, Bosch, like many of the Dutch illuminators, saw in terms of light and colour. Nowhere is this painterly vision more strikingly demonstrated than on the outer wings of his altarpieces. Their subdued monochromatic colour follows a convention common in Netherlandish altarpieces, but where the older artists exploited grisaille to present an illusion of sculptured stone figures set in niches, Bosch creates misty landscapes, as in the St James wing from the Last Judgment in Vienna and the exterior of the St Anthony triptych, and above all in that most unsculptural of subjects, the vision of St Gregory in the Prado Epiphany.

This sensitivity to the optical qualities of form enabled Bosch to create some of the most original landscapes of the period. These still function traditionally as backdrops to his figures, but they assume greater prominence and often reflect the mood and meaning of the subject. Unlike the professional landscape painters of the sixteenth century, Bosch never developed a formula: his landscapes show a wide range of types. Some are as alien as the surface of another planet, others as familiar as a painting by Jan van Goyen. Indeed, Bosch seems to have responded to the flat, monotonous terrain of his homeland as freshly as did the Dutch landscapists of the seventeenth century. The great expanse of land and water that recedes from Patmos in the Berlin St John, for example, may bring to mind the panoramas of Jacob van Ruisdael, and in the monochromatic veil which he drew across the background of the Rotterdam Wayfarer, Bosch hit upon a way to render the damp Dutch atmosphere which remarkably anticipates Jan van Goyen. In this, Bosch was inspired, perhaps, by his own landscapes in grisaille, such as the one in the Vienna Last Judgment. But unlike his successors, Bosch never discovered the expressive qualities inherent in balancing a low horizon with a great extent of cloudy sky, although in the Crucifixion scene on the back of the Berlin St John he came very close to doing so. In other paintings, however, as in the Rotterdam St Christopher, the Prado Epiphany, and the Haywain triptych, he tilted up the ground plane in an old-fashioned manner, displaying a succession of hills, valleys and lakes which merge imperceptibly into the distant horizon.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Wayfarer, 1500

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

Hieronymus Bosch, Garden of Earthly Delights (detail)

The meticulous techniques of the older Netherlandish masters were well adapted to their static, eternal images; they constructed a painting as carefully and as methodically as the goldsmith produced a censer. To this tradition of panel painting Bosch brought something of the freedom and originality that we find in the Dutch illuminators. In his hand, brush and pen caught the changing evanescent shapes of light and shadow, and rendered incandescent visions as readily as the most concrete realities.

The rapid diffusion of Bosch’s fame and art throughout Europe can be measured by a succession of dates. In 1504, Philip the Handsome commissioned a Last Judgment from him. Philip’s mother-in-law, Queen Isabella of Spain, owned three of Bosch’s paintings at her death in 1505; they were probably gifts from the Burgundian court. By 1516, another picture belonged to Margaret of Austria, regent of the Netherlands after Philip’s death. In 1521, four years after Antonio de Beatis saw the Garden of Earthly Delights in Brussels, several more of Bosch’s works were in Cardinal Grimani’s palace in Venice; among them may have been the Paradise and Hell panels now in the Palace of the Doges. In 1524, a picture which may have been the Stone Operation now in Madrid was recorded among the possessions of the Bishop of Utrecht. Some time between 1523 and 1544, Damiâo de Goes, a Portuguese agent in Flanders, acquired the St Anthony triptych now in Lisbon. An inventory of the furnishings of Francis I of France, made in 1542, lists a set of tapestries after Bosch’s composition, including the Haywain and the Garden of Earthly Delights.

Hieronymus Bosch, Garden of Earthly Delights (detail)

Hieronymus Bosch, Garden of Earthly Delights (detail)

Beyond the borders of the Netherlands, however, Bosch’s pictures found the most favour in Spain. The union of the houses of Burgundy and Spain through royal marriages brought numerous Spaniards to Flanders, where they often became avid collectors of Bosch’s art. Felipe de Guevara probably inherited his collection of Bosch’s paintings from his father, a member of the Burgundian court. The third wife of Hendrick III of Nassau, Mencia de Mendoza, returned to Spain after her husband’s death in 1538 with several paintings by Bosch. These did not include, however, the Garden of Earthly Delights which came into the hands of one of Hendrick’s descendants, William the Silent. This work and a number of other paintings by Bosch were confiscated by the Duke of Alva during his occupation of the Netherlands; from Alva they eventually came into the hands of Philip II.

Bosch’s spacious panoramas probably influenced the landscape style of Joachim Patinir, the earliest professional landscape painter in Western art. Bosch’s moralizing scenes, utilizing figures and scenes from everyday life, contributed significantly to the development of Flemish genre painting. However, it was his diabolic imagery which exerted the greatest impact on sixteenth-century Flemish art. Three Bosch-like compositions swarming with devils were engraved by the architect Alart Du Hameel before his death in 1509, and Bosch-like motifs can be found in scores of Flemish paintings, often of poor quality.

Hieronymus Bosch, Garden of Earthly Delights (detail)

Jan Mandijn, Landscape with the Legend of St Christopher, c.1520

Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

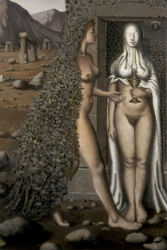

Towards the middle of the century, Bosch’s influence reached its peak in Antwerp, the great picture factory of Northern Europe, perhaps in reaction to the Italianate style prevailing in official and ecclesiastical art. Among his imitators at this time can be found Jan Mandyn and Pieter Huys. Likewise, Pieter Bruegel the Elder improvised freely on Bosch-like themes.

In the hands of this horde of imitators and followers, the deeply religious and didactic content of Bosch’s imagery quickly evaporated, leaving only whimsical forms capable at most of arousing a pleasant shudder in the spectator. Hell becomes an infernal amusement park, a Disneyland of the afterlife, where devils seem to display themselves more for the titillation of the damned than for their torment.

Pieter Huys, Hell, 1570 | Museo del Prado, Madrid

Attibuted to Pieter Huys, The Temptation of St Anthony, (between 1545–1584) | Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC

Demons parade aimlessly around St Anthony, and the courtesans who tempt him are much more voluptuous than Bosch had ever painted.

Only Pieter Bruegel was able to restore something of the original meaning to Bosch’s grotesques, especially in his drawings of the Seven Deadly Sins; but even his infernal landscapes are somewhat prosaic, and, except in the Fall of the Rebel Angels, his monsters are too obviously pieced together from the facts of everyday life to be completely convincing. In fact, Bruegel most closely approaches Bosch in spirit where he differs from him most in detail, namely in the Triumph of Death in Madrid. The brilliant diversity of Bosch’s devils has been replaced by the monotony of an army of human skeletons, but their relentless march across the earth, devastating everything in their path, presents an image of universal destruction no less compelling than Bosch’s apocalyptic scenes.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Triumph of Death, c.1562 | Museo del Prado, Madrid

Hieronymus Bosch, Tabletop of the Seven Deadly Sins, 1505-10 | Museo del Prado, Madrid

As might be expected, however, it was chiefly in Spain that Bosch’s paintings were regarded with some of the same spirit which had conceived them. Not only did the largest proportion of his works find their way to Spain, but it was also here that medieval attitudes lingered on long after they had disappeared elsewhere in Europe. In the Escorial, the cells of the monks were filled with his pictures, and in the privacy of his bedchamber the gloomy Philip II reflected on the state of his soul before the Tabletop of the Seven Deadly Sins. Bosch’s pictures must have appeared to Philip as they did to Fray José de Sigüenza, who insisted that they were not absurdities ‘but rather, as it were, books of great wisdom and artistic value. If there are any absurdities here, they are ours, not his; and to say it at once, they are a painted satire on the sins and ravings of man.’ No modern critic has more aptly characterized the art of Hieronymus Bosch.

Hans Belting

Hieronymus Bosch: Garden of Earthly Delights

Walter S. Gibson

Hieronymus Bosch

Pilar Silva Maroto

Bosch: The 5th Centenary Exhibition