Leonor Fini

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Five Chapter 18

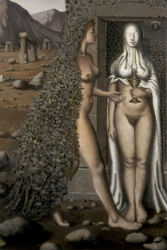

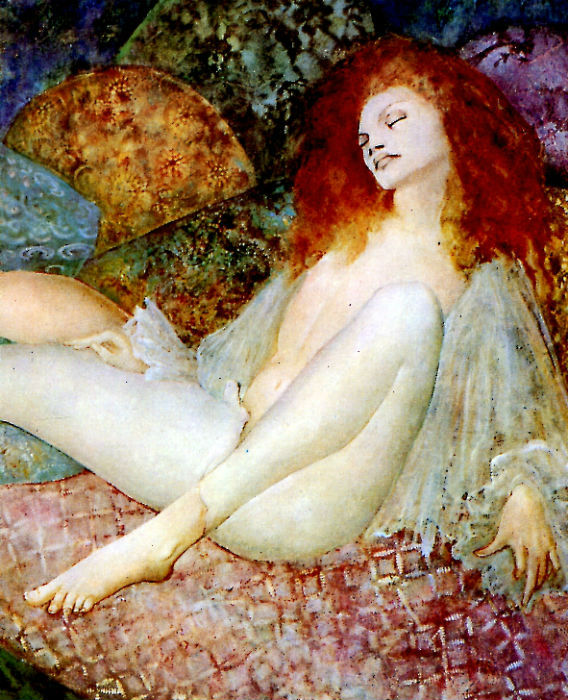

[Marietta:] Have you seen Leonor Fini’s illustrations for Histoire d’O? ‘Illustrations’ is hardly the word—they’re more like a visual echo of the text, dark-coloured washes over lithographed pen-and-ink drawings.

Leonor Fini, Histoire d’O

Leonor Fini, Histoire d’O

Very evocative, but far removed from my own fantasy when reading Réage’s love letter.

I do like Fini’s eroticism, though.

Leonor Fini, Histoire d’O

JEAN-CLAUDE DEDIEU ON LEONOR FINI

Leonor Fini, or Contradiction

From Arlette Souhami & Richard Overstreet, Leonor Fini (Lausanne: Editions Favre, 2001) | Text edited for readability and translated here by Richard Jonathan.

Leonor Fini, Elective Antinomies, 1959

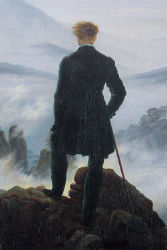

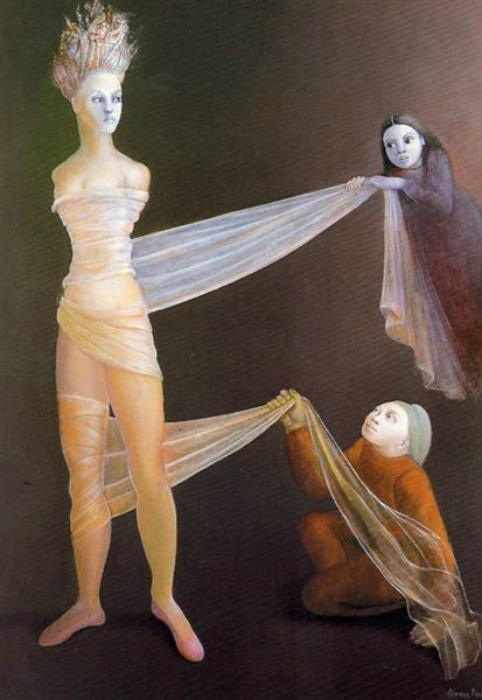

In Leonor Fini’s art, everything conspires to increase the distance that separates the spectator from what he beholds. First there are the subjects themselves; the strange scenes, the theatricality, the restrained violence. But there’s also—together with the beauty, the elegance, the sleek surface of the paintings—a ‘touch-me-not’ quality that keeps us at a distance. The action is being staged; acts becomes gestures. We soon realize that meaning is to be sought beyond what the painting immediately reveals. Indeed, something is signalling its presence to us and we cannot recognize it right away. And thus it is from excess, from not being realistic, that Leonor Fini’s universe draws its poetry.

But not realistic in what sense? It’s obvious that Fini’s painting does not refer to any form of nature. Instead, it exalts subjectivity and desire, fantasy and culture. (Come to think of it, what would constitute realistic art? An art based on a belief in a coherent world that the artist would calmly set out to copy?) The work of Leonor Fini says this: No more than for the individual, reality does not coincide with itself. Its appearance is insufficient—it is an apparition of uncertain meaning. The visible is haunted by the invisible. There is no world sealed in upon itself in the certainty of its identity, but rather a ceaseless becoming that effects transmutations. What art explores is this process of change.

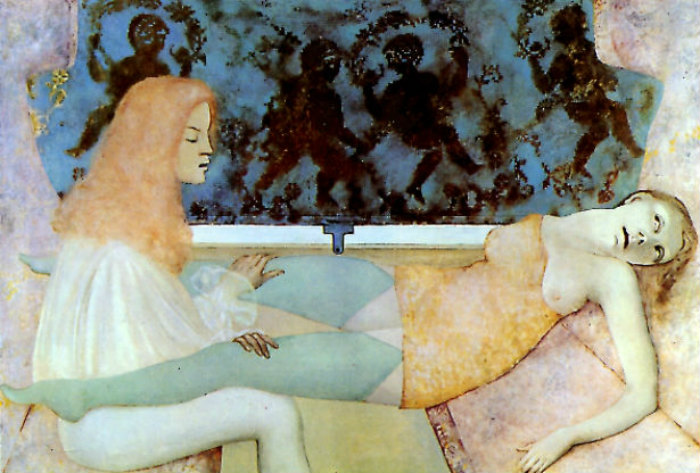

Leonor Fini, In Dawn’s Shadow, 1984

Leonor Fini, The Caryatid Set Free, 1986

Everything is dual. Life and death—like day and night, man and animal, animal and plant—are no longer separate. From reciprocity and conjunction arise secret figures, uncanny signs. The fantastic results from this capacity to suggest, in the appearance of something, its opposite. And thus the favoured trope in Fini’s language is contradiction, as the titles of her paintings often testify: Elective Antinomies; The Caryatid Set Free; In Dawn’s Shadow. Instead of resolving the enigma of the work, the titles deepen it.

The angels, sphinxes, vampires, furies and sleepwalkers that pass through the lunar kingdoms of Fini’s imagination are all demons—their nature is intermediate between human and divine. Thus, closer to both gods and beasts, they surpass humans. And since they do not belong to humanity, they can show that humanity does not belong to itself: it is but a fiction by which man reassures himself, gives himself recognizable contours. Fini’s creatures are survivors of another time and place; in embodying the unknown, they incarnate the mystery of existence.

Leonor Fini, Extreme Night, 1977

Leonor Fini, L’Élue de la nuit, 1986

Like freaks, the creatures that populate Fini’s world both attract and disturb. And Fini herself participates in her world. The obsession with metamorphosis expresses itself in masks and costumes.

In all Leonor Fini’s paintings, passage is the recurring theme. There is no rupture, only continuity, contiguity, a generalized contagion—one time to another, one place to another, one being to another. ‘Other’, indeed, is often the adjective that specifies (without ever defining) the subject of a Fini painting, as in The Other Side and The Window of the Other Summer. The unity of Leonor Fini’s work, then, the common thread running through its diversity, is the theme of becoming. It nourishes a vital reverie, is based on a metaphysical background drawn from alchemy, and accounts for a poetics of nostalgia in which absence is not opposed to presence.

Leonor Fini, Passante II, 1981-82

Leonor Fini, Before Sleep, 1980

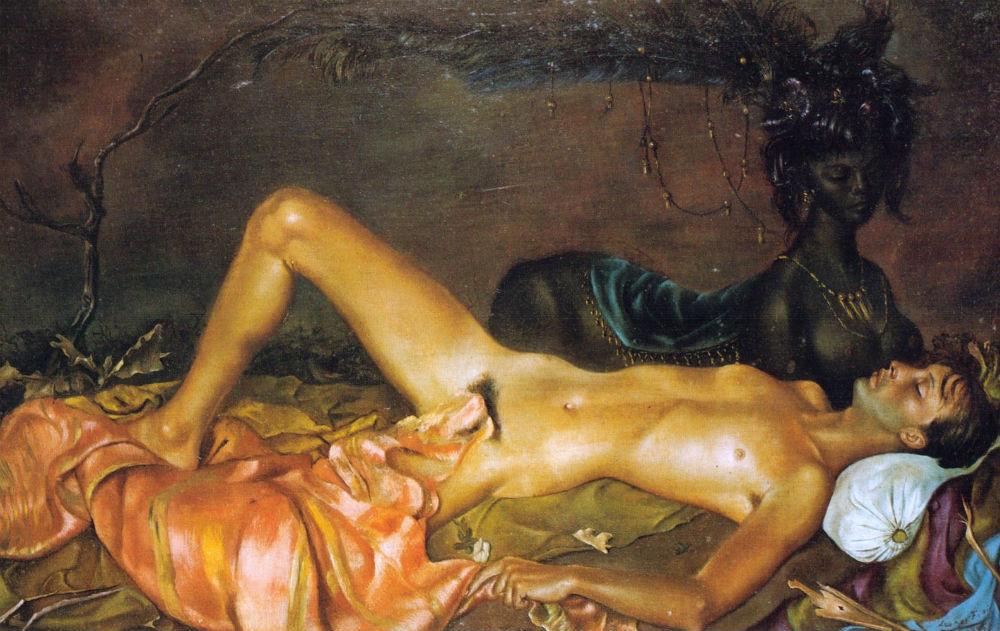

Apparently dissimilar themes—sleep, travel— can be seen as variants of the principle of becoming. In sleep we leave the order of the daytime world and abandon ourselves to another dimension; we become indifferent to time and space, interdiction and contradiction. For Fini, sleep is fascinating because it gives access to a world that is as ‘realistic’, as full and autonomous, as the daytime world: we inhabit the night.

As for travel, in changing places the passenger is, in a sense, only fulfilling his destiny; his wandering is but the outcome of his condition: an exile. Indeed, the livable place is not the one where we are but the one we are travelling to: it is not the destination, but the journey itself.

Leonor Fini, Voyage with No Moorings, 1986

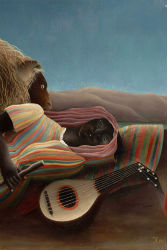

Leonor Fini, Travellers at Rest, 1978

Beyond what might have set them in opposition to each other (as movement and stasis are opposed to each other), travel and sleep intersect. Their encounter intensifies, for example, the mysterious beauty of Travellers at Rest. What do we know of sleep, outside of what we believe we snatch of it upon awakening? Is it not an impossible experience? If truth be told, we know nothing of it that is not derived from wakefulness. Absorbed in the contemplation of sleeping faces and bodies, at once present and absent, we observe how the sleepers seal up within themselves this enigmatic contradiction. Note how the colours effect a fusion between the characters and the world that suggests a surrender to the night: existence is but ashen clarity, sidereal dust.

This theme appears very early in Fini’s painting, where surrender to sleep comes across as a sweet but vulnerable voluptuousness, as in Chthonian Divinity Watching Over a Young Man’s Sleep.

Leonor Fini, Chthonian Divinity Watching Over a Young Man’s Sleep, 1946

Leonor Fini, The Train, 1975

As for the train series, it gives expression to the paradox of the still movement of travelling sleepers, carried away in their immobility within the enclosed carriage.

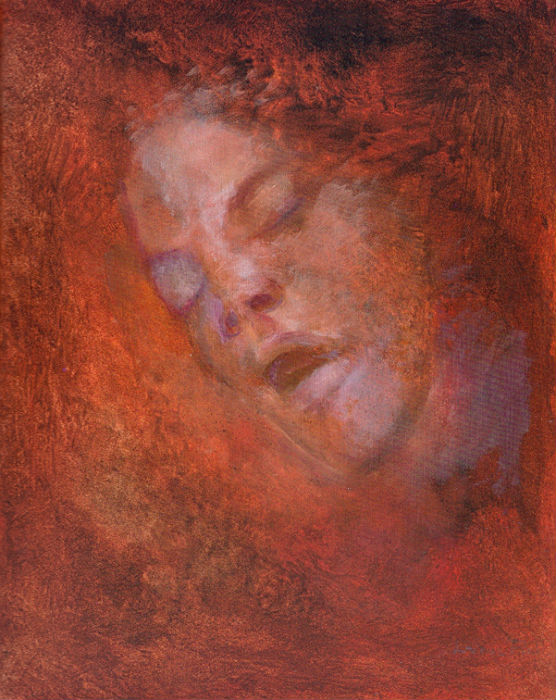

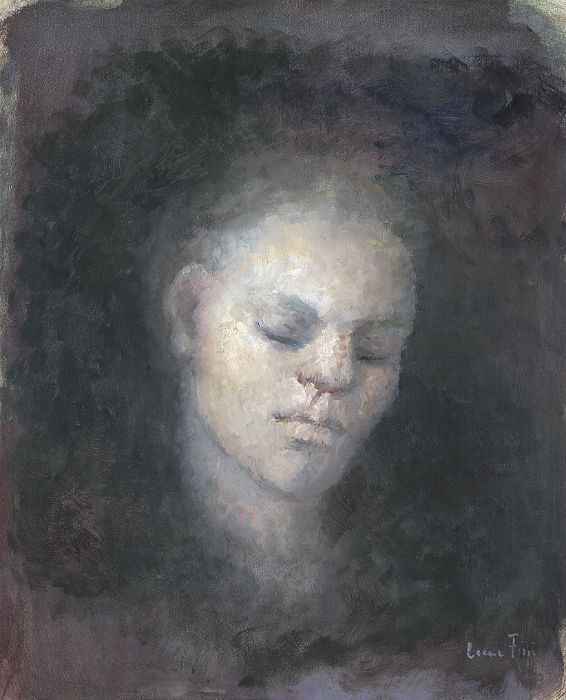

In the portfolio Passengers: Thirty Faces by Leonor Fini (1992), many of the faces are asleep (or at least their eyes are closed). Though eighteen years distant from Faces for Délie: Twelve Lithographs by Leonor Fini (1974), they have the same faraway, forsaken expression. A partial effacement highlights the fragility of an existence destined to fade away—in sleep, the temptation of nothingness is already inherent.

Leonor Fini, Passenger XXIV, 1986

Leonor Fini, Passenger VII, 1989

In these works, the process and the product are seen simultaneously: a line retraces itself, a colour fades away, a shadow hesitates, a hairdo comes undone, a mouth opens. Barely distinguishable from the background colours (sepia, grey, burnt umber, sienna, ochre), the faces emerge from the primeval elements, as it were, to make visible both the birth of painting and the birth of a face.

The creative gesture, leaving traces of itself, making itself visible as a material act, recalls both the natural phenomena whose genesis it seems to imitate and the art which discerns a latent meaning in the phenomena. These semblances of undersea springs, of froth, fog and clouds are no longer quite the forms of nature since they are already the expression of a face. ‘Imaginary portraits’, not copies, these faces poetically realize the essence of the image that Plato defined as ‘the intermingling of being and non-being’.

Leonor Fini, Passenger XV, 1989

Leonor Fini, Passenger IX, 1990

Far off is the idea of death. It is evoked only through destroyed appearance, or more precisely, through the effect of time, the feeling of a distant past, and the evidence that something was and no longer is.

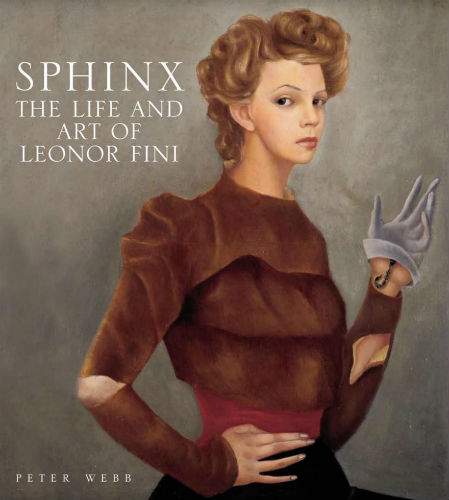

PETER WEBB ON LEONOR FINI

From Peter Webb, Sphinx: The Life and Art of Leonor Fini (New York: The Vendome Press, 2009)

LEONOR FINI: WOMEN IN CONTROL

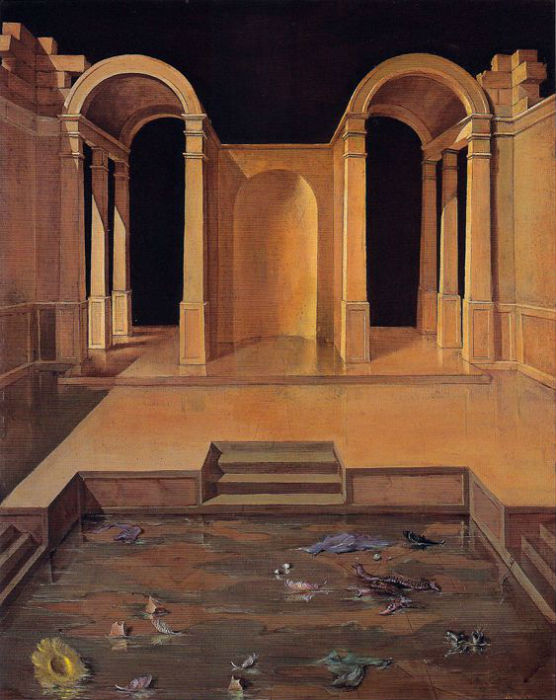

D’un jour à l’autre I (From One Day to Another I, 1938) depicts a deserted classical villa, reminiscent of a Paul Delvaux setting, with steps down to a pool on whose surface can be seen flowers, feathers, eggshells, and fish bones. This painting is half of a diptych, the other half being…

Leonor Fini, From One Day to Another I, 1938

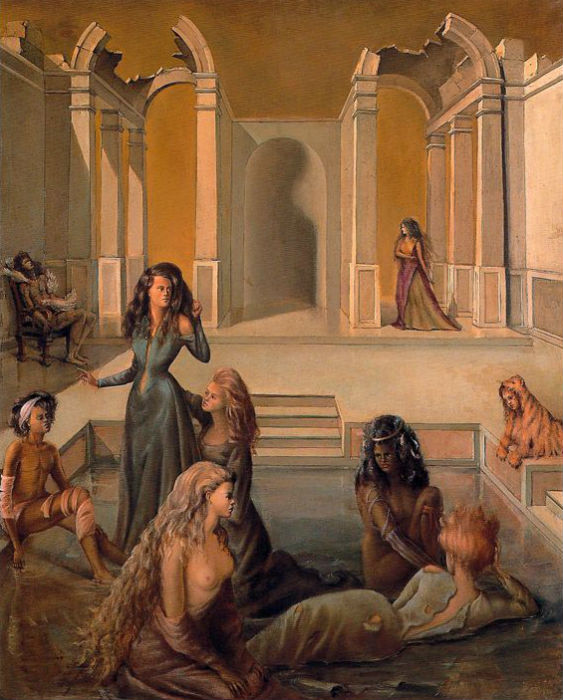

Leonor Fini, From One Day to Another II, 1938

… D’un jour à l’autre II (From One Day to Another II), in which the same villa is now partly in ruins and five provocative women, some clothed, some nude, are talking together in the pool. They ignore a nude and bandaged boy in the pool beside them, as well as a man tied to a chair being attacked by three chickens and a man emerging from a tiger skin beside the pool. These two paintings present a nightmare that seems to reflect the atmosphere of the time in Europe. Leonor told the author that the villa had been ‘ruined by the cruel cataclysm of war.’ Here again, the most prominent woman is clearly Leonor herself.

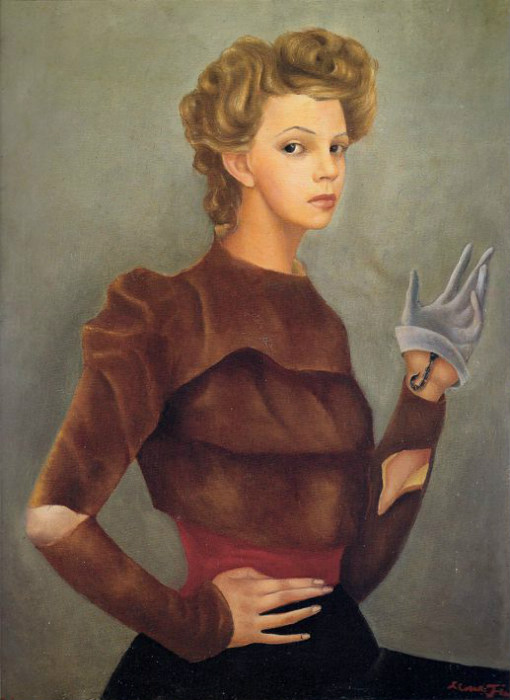

Also from 1938 are two paintings of young women in armour up to their breasts, which seem to have been studies for La Chambre noire of 1939.

Leonor Fini, Woman in Armour I, 1938

Leonor Fini, The Black Room, 1939

In this painting the theatrical curtains of an alcove are drawn back to reveal Leonor in characteristic striped stockings seated on a bed holding the hand of an androgynous young person lying beside her. In an atmosphere of mystery and drama, both are looking towards the tall and imposing figure of Leonora Carrington, surrounded by discarded clothing but wearing a metal breastplate, who stands triumphant and powerful in the position of guardian and protector.

Autoritratto con Chimera (Self-portrait with Chimera, 1939) shows the artist with an abundance of long black hair and wearing a dress but with the wings and tail of a bird, standing beside a hybrid creature with the body of a lion, the upper torso of a nude woman, extended wings, and the head of a cat. This extraordinary painting of Leonor as a deity, half-animal and half-human, which has some of the shock of an Ernst collage, includes a forerunner of her characteristic sphinxes. She herself chose the word ‘ceremony’ to describe these and many later works: ‘The “ceremonies” are chosen actions where disorder, ugliness, incoherence are rejected, abolished.’

Leonor Fini, Self-Portrait with Chimera, 1939

Leonor Fini, Self-Portrait with Scorpion, 1938

These paintings mark an important stage in the progress of Leonor’s art. They demonstrate not only the lessons she learned from surrealism but also her independence from the movement. They create an erotic dream world in which women are in control, a world that would become characteristic of so many of her later images, such as the numerous manifestations of the sphinx. They show a concern with ancient ceremonies and rituals, a mythology based on the artist’s own psychological and sexual experiences of both men and women.

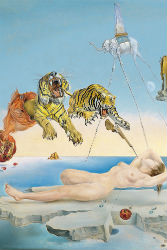

LEONOR FINI: EROTICISM

In Phoebus Asleep and L’Entre-Deux, two androgynous figures in varying degrees of undress play sexual games among the brightly coloured cushions of a luxurious chaise longue.

Leonor Fini, Phoebus Asleep, 1967

Leonor Fini, Phoebus Asleep, 1967 (detail)

These works epitomize Leonor’s concept of eroticism, which was more concerned with beautiful clothing, draperies, fabrics, veils, silks, and satins than with nudity, and which concentrated on suggestion and desire.

She often spoke of the need for a sense of decorum that balanced what was experienced with what was felt: ‘The decorum must be right; it will be if it supports the eroticism. If one experiences this sensation, that proves that it is correctly carrying out its connecting role.’

Leonor Fini, L’Entre-Deux, 1967

Leonor Fini, Along the Way, 1967

Leonor continued to explore the intimacies of two figures in a series of paintings set in train compartments. In Along the Way, the right-hand figure lies back in her seat with dilated eyes, open mouth, and one breast exposed, using stockinged legs to embrace her partner, whose hands explore her body. In 1975 Leonor wrote: ‘What can be more limiting than a train compartment, where almost everything is forbidden apart from sitting still? As a child, I imagined that any transgression would cause a railway accident. Train compartments are therefore both distressing and protective, places of passing complicity where one sleeps false sleep in which one allows oneself to escape into claustrophobic, ecstatic, or criminal reveries.’ As was so often the case, the ambiguities of such situations created the attraction for Leonor. In a conversation with the author, she recalled: ‘Train journeys seem boring nowadays, but in the past I found them dramatic. They could be scenes of adventures, of unexpected meetings. They seemed to me the perfect setting for erotic situations to develop. That was why I painted so many images set in train compartments during the 1960s.’

In 1968 Fini painted The Blind Ones: two almost-naked women making love on the floor, eyes closed, mouths open, in a paroxysm of desire. The woman underneath, who seems older, holds her partner in a tight grip. The pallor of the two women suggests a medieval scene of Death and the Maiden.

Leonor Fini, The Blind Ones, 1968

Leonor Fini, The Botany Lesson, 1974

In The Botany Lesson, a naked woman uses an enlarged cross-section of a flower to teach a strange hybrid creature [or just a girl] the similarities between the primeval beauty of the female sexual anatomy and that of the structure of a flower.

In Kinderstube, a young girl crouches down and sees a lizard in a hand mirror on the floor, directly above which stands a girl in a transparent shift with her legs apart. The lizard clearly symbolizes the girl’s vulva, and this symbolism is continued in the tulip decorations on the carpet. Through the door comes an old woman in a wedding dress bearing a bridal bouquet. The sexual significance of this image was discussed by the critic Claude-Frédérique Sammer: ‘The little halo of the mirror is in itself a concentration of all the painting’s obscenity and force. It personifies juvenile provocation, welds an alliance between the two girls and creates for the viewer a potential anxiety through this uneasy contemplation of the female body. This scene manages to express with delicacy and discretion all the transgression contained within the limits of a private place.’

Leonor Fini, Kinderstube (Children’s Room), 1970

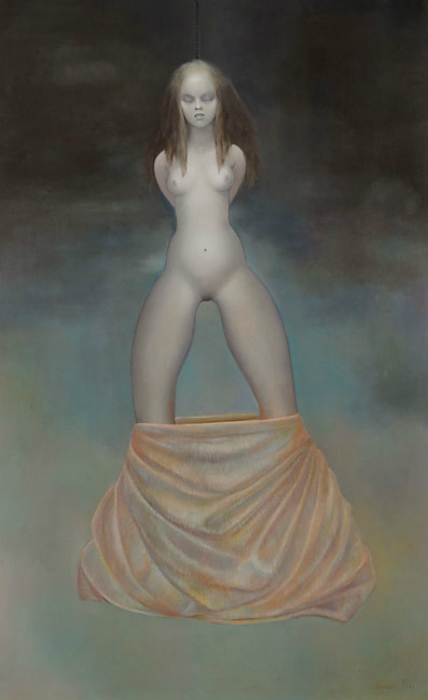

Leonor Fini, The Pearl, 1978

SPHINXES, WITCHES AND GIRLS:

Reconsidering the Female Monster in the Art of Leonor Fini

By Rachael Grew

The focus on adolescent sexuality found in Kinderstube can also be seen in The Pearl. Though the girl appears to be hanging from a rope (perhaps suggesting auto-erotic asphyxia), the fact that she does not seem to be in any pain gives this work a transcendent quality, suggesting that this exposed sexuality is to be celebrated.

Leonor Fini (Lausanne: Editions Favre, 2001)

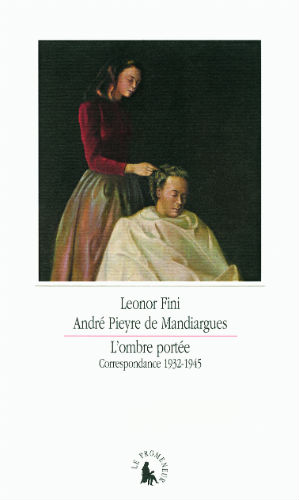

Fini-Mandiargues, Correspondence 1932-45

Leonor Fini at her country home in Touraine, France, 1986

Leonor Fini at her country home in Touraine, France, 1986