Dorothea Tanning

Dorothea Tanning, Self-Portrait on 30th Birthday, 1942

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Nine Chapter 9

Shimmering water, shallow expanse, a caress unravelling a skein of ripples: The wind picks up. Look! A scattering of sanderlings, pale in their winter plumage, busily pecking their way about. Paradoxical birds: Swift and direct of purpose, yet looking random and lost.

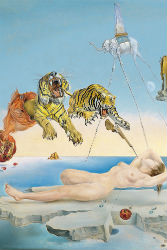

̶ If not Delvaux, then who do you like, Sprague, in surrealist painting?

̶ Dorothea Tanning. Eine Kleine Nachtmusik. Do you know it?

̶ No.

̶ It’s magnificent!

̶ Where can I see it?

̶ In the Tate. And Birthday I like even better.

̶ Birthday?

̶ Her self-portrait on her thirtieth birthday. Still in a private collection, unfortunately. Look! Sanderlings and…

̶ Oystercatchers!

While the black-and-white birds with red beaks poke about, the sanderlings skip along the foamline, fleeing the wash of the waves only to pursue the backwash seaward, sticking their beaks into the bubbling sand.

DAWN ADES ON DOROTHEA TANNING’S ‘BIRTHDAY’

From Surrealism: Desire Unbound, Jennifer Mundy, editor (London: Tate Publishing, 2001), p. 197

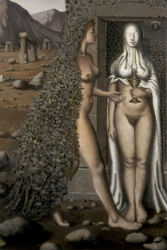

This self-portrait, painted on the occasion of her thirtieth birthday, was on her easel when Max Ernst visited Dorothea Tanning for the first time, in the course of a tour of New York studios to select an exhibition of work by women painters. Discovering not only a gifted artist with an intelligence, pride and curiosity to match his own, already working in a surrealist manner, but also a chess player, he soon came to stay. To a collector visiting the couple shortly after, Ernst announced that the painting was not for sale. ‘I want to spend the rest of my life with Dorothea. This picture is part of that life.’ Tanning tells this anecdote in her memoirs, also entitled Birthday, the name Ernst had given the self-portrait.

In her memoirs she tells of the painting’s origin in her fascination with the array of doors in the six almost empty rooms of her apartment, their imminent opening and shutting and potentially endless extension. like the surrealists’ favourite image of the labyrinth, the doors and hidden rooms symbolise an inner as much as an outer unknown, the chambers of the unconscious mind. Her gaze and her posture, holding a door knob with one hand and looping up the folds of a skirt with the other in a gesture that recalls the female figure in Jan van Eyck’s painting commonly known as The Amolfini Marriage (1493), express both anticipation of an unknown future and fear of the void.

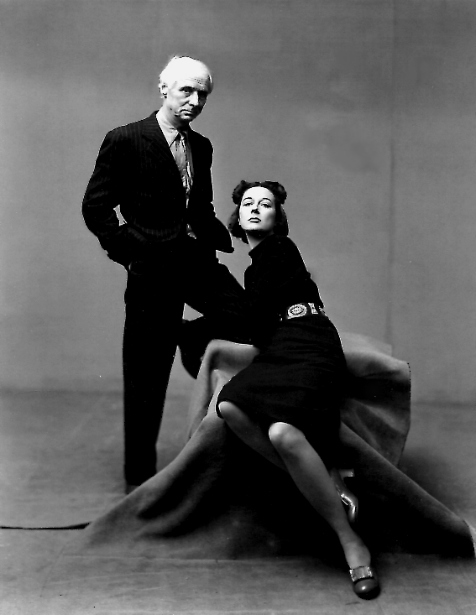

Max Ernst & Dorothea Tanning | Photo: Iriving Penn, 1947

Dorothea Tanning, Birthday, 1942 (detail)

The bare geometrical setting is the perfect foil for her elaborate self-image, with its odd conjunction of protective layers and erotic exposure, wholly modern face and hair and antique or fairytale garb. A theatrical, possibly male, royal purple and gold jacket with lace cuffs reveals her breasts, while tangled roots and twigs resembling mistletoe, but containing writhing couples, partially encase her, like the brambles round the Sleeping Beauty or the bush into which the nymph Daphne was transformed. It is as though she is trying out myths of nature and of culture and none is quite cut to ha figure. At her feet is a composite creature, a lemur with wings. The lemur is a nocturnal animal found only in Madagascar, where it has long been associated with night and spirits of the dead.

In Birthday Tanning represents herself poised, and as if in a dream, on the eve of a discovery, perhaps about to take flight on this night creature. One should not overlook the unusual adoption, in the context of a budding surrealist who was to go on to great pictorial audacity, of a transparent naturalism: there is nothing, formally speaking, to disturb the scene. Figures and objects are to scale; there is neither distortion nor disruption of space, nor the free gestures of automatism. The realism is neither photographic, nor rudimentary, nor naive, nor exaggerated to mimic nineteenth-century academic painting. This makes its evocation of a world beyond the immediate senses all the more mysterious and effective.

Dorothea Tanning, Birthday, 1942 (detail)

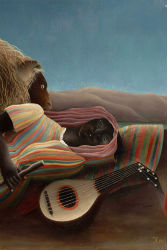

Dorothea Tanning, Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, 1943

DOROTHEA TANNING ON ‘EINE KLEINE NACHTMUSIK’

It’s about confrontation. Everyone believes he/she is his/her drama. While they don’t always have giant sunflowers (most aggressive of flowers) to contend with, there are always stairways, hallways, even very private theatres where the suffocations and the finalities are being played out, the blood red carpet or cruel yellows, the attacker, the delighted victim…

—from an unpublished letter from the artist to the Tate Collection, 1999, quoted in Victoria Carruthers’ essay ‘Dorothea Tanning and Her Gothic Imagination,’ Journal of Surrealism and the Americas 5, no. 1 (2011), p. 146.

At night one imagines all sorts of happenings in the shadows of the darkness. A hotel bedroom is both intimate and unfamiliar, almost alienation, and this can conjure a feeling of menace and unknown forces at play. But these unknown forces are a projection of our own imaginations: our own private nightmares.

—from an unpublished interview with Victoria Carruthers, 2005, quoted in her essay ‘Between Silence and Sound: John Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen and the Sculptures of Dorothea Tanning,’ Art, History and the Senses: 1830 to the Present, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing, 2010, p. 112.

Courtesy of the Dorothea Tanning website

Dorothea Tanning at home in the south of France, c.1955

Dorothea Tanning at home in the south of France, c.1955

Dorothea Tanning at home in the south of France, c.1955