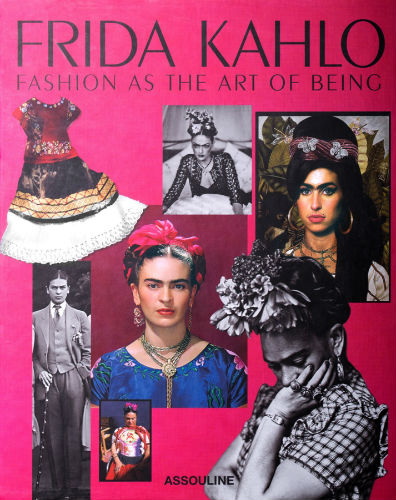

Frida Kahlo

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Intermezzo 2: Vika

Sitting beyond the shadow of her destiny, Vika sips her Krāslavas beer. From gunmetal to clear blue her eyes veer as she celebrates her freedom: Once I’d have been condemned to die here. The grinding of a streetcar rounding a curve leads to a conversation about Frida Kahlo; a palimpsest of graffiti under peeling paint leads to an exchange about John Lennon: Vika says her father once got arrested for writing ‘Beatles’ on a wall. Tar and rust and gasoline, oily brine and dust: Vika rubs her eyes and slips on her sunglasses. She smiles as I stare through her grey-green disguise; holding her gaze, I caress her cheek.

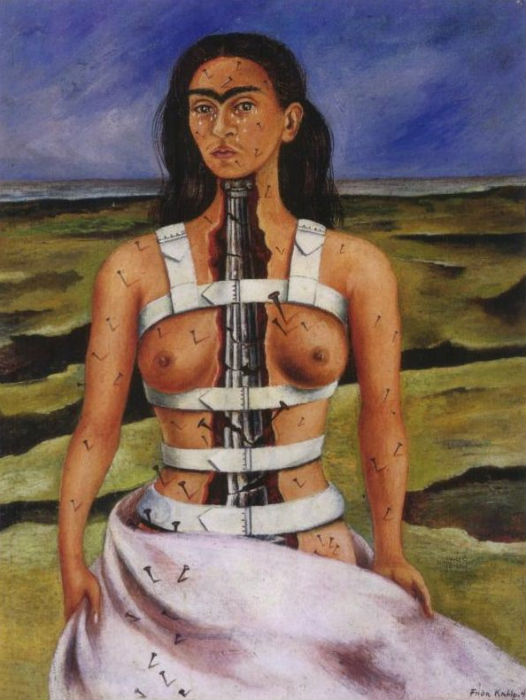

Frida Kahlo, The Broken Column, 1944

FRIDA KAHLO: ELEMENTS OF A BIOGRAPHY

From Charles Gardou, « Frida Kahlo : de la douleur de vivre à la fièvre de peindre » (Reliance, 2005/4 No 18, pp. 118-31)

These passages translated by Richard Jonathan.

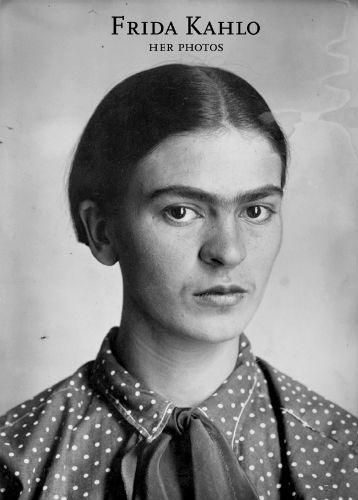

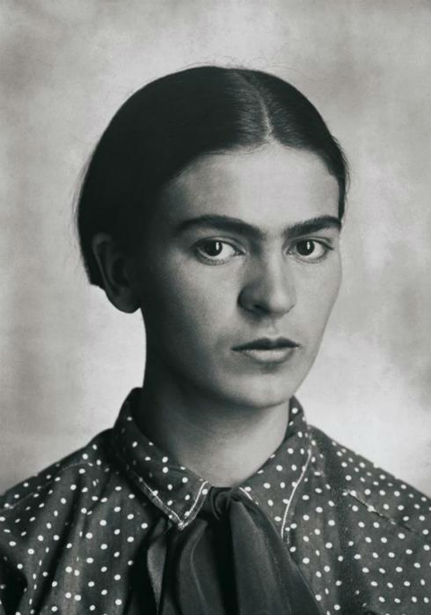

Guillermo Kahlo, Frida, 1926

The third of four daughters, Frida Kahlo found an anchor for her identity in the figure of her father, ‘with his generous character, refined and intelligent, and his courage, because’, as she was proud to say, ‘despite having suffered from epilepsy for sixty years, he never stopped working and he fought against Hitler’. Very early she learned how to care for him during his epileptic fits. She shared with him the same experience of fragility, sickness and solitude. Germano-Hungarian, Guillermo Kahlo was an official photographer of Mexico’s cultural heritage during the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz. He shared with Frida his passion for the art and archaeology of Mexico.

The source of the quotation is the dedication Frida wrote at the bottom of her painting, Portrait of Don Guillermo Kahlo.

A tragedy brutally transformed her life: She was but 18 when an accident tore her existence in two. In the collision of a tram and the bus where she had just taken a seat, a metal rod literally transfixed her, running through her body from the back to the uterus. She suffered multiple fractures to her spine, ribs, pelvis, hips and right leg; her right foot was crushed. The steel handrail, entering her body from the left side, came out through her vagina: ‘The shock threw us forward’, she explained, ‘and the handrail rod pierced through me like the sword that finishes off a bull’. She then added, with the humour, often macabre, that served her as armour: ‘And that’s how I lost my virginity’. If she survived this terrifying accident, the suffering that followed was unbearable. She spent a month in hospital, on her back, imprisoned in both a plaster cast and a coffin-like box.

The source of the quotation is Frida’s letters, edited and introduced by Raquel Tibol.

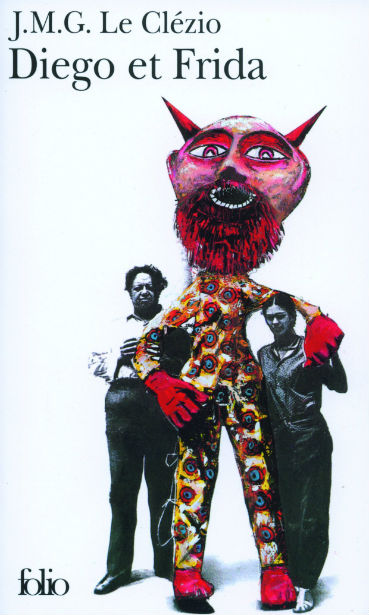

J.M.G. Le Clézio, Diego et Frida

She did not come early to painting as a vocation. No, it was painting that, after her accident, came to spring forth from her wounds, her blood, her guts, her intimate self, her fantasies. It is a kind of confession in images, a way to ward off death: ‘All her disillusions, all her tragedies, that immense suffering that is woven into her life, all is revealed there, in her painting, tranquilly, with no false modesty and with an exceptional independence of mind’. Several of her paintings have surreal and fantastical elements, but in none of them does she completely detach herself from reality and concrete experience. Consequently, she vigorously refused to belong to any school, whatever the stripe, despite André Breton trying to claim her for the Surrealists.

The source of the quotation is Le Clézio’s biography of Diego and Frida.

Her representations of female sexuality and the female body—less idealized, more realistic, sometimes rather sinister—broke the taboos of her time. She is ‘the first woman in the history of art to have addressed, with absolute and merciless sincerity—with even, one could say, a calm cruelty—the general and particular themes that uniquely concern women’. Characterized by a complexity of which she was acutely aware, she refused to comprise with social convention. She had no qualms, especially during the last years of her life, about displaying her bisexuality in her paintings. As the years went by and her physical frailty made sex with men more difficult, she turned toward women, and in particular to Diego’s mistresses.

The source of the quotation is Raquel Tibol’s introduction to Frida’s letters.

Andrea Kettenmann, Kahlo

In 1953 the gangrene in her right leg started spreading. The pain having become unbearable, in August the doctors decided to amputate the leg at the knee. If the operation brought her some relief, it also drained her of the energy that had always sustained her. Wild mood swings then ensued. One day, euphoric, she would say : ‘What do I need feet for if I’ve got wings to fly?’ Another day, she’d write: ‘They amputated my leg six months ago which seemed like an eternal torture and sometimes I lost my head. I still feel like killing myself. Only Diego prevents me from doing it, since I imagine he would miss me. That’s what he says and I believe him. But never, in all my life, have I suffered more. I will wait a little longer.’ She was still alive, but her hope was dead.

The source of the quotation is Frida’s letters, edited and introduced by Raquel Tibol.

FRIDA KAHLO: SELF-PORTRAITS

Dawn Ades

From Surrealism: Desire Unbound, Jennifer Mundy, editor (London: Tate Publishing, 2001), p. 197

Frida Kahlo was her own favourite subject. Over and above the self-portraits, she used her own image in imaginary or symbolic scenarios to represent the experiences, desires and sorrows of her tumultuous life. Self-Portrait with Monkey and Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair were painted during the year of her divorce from Diego Rivera (they remarried at the end of the same year, 1940).

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair, 1940

The mood of Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair is both angry and forlorn; in retaliation against Rivera she has cut off the long hair he loved, stripped herself of all feminine adornments save earrings and shoes, and donned on outsize masculine suit. The shorn hair horrifically multiplies as though uncannily alive across the barren landscape.

The step from the reality of her body to a world of the imagination, of signs and symbols, was easy for Kahlo. Unfettered by either the didactic realism of the Mexican muralists or the formal concerns of modernism, she forged a unique style out of her various sources: the stiff but charming regional academic painting of nineteenth-century Mexico, and popular art, especially retablos. These small, naive, usually anonymous paintings depicted scenes of miraculous recovery from sickness or danger, with a written dedication to the saint in whose shrine it would be hung. Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair uses this device but transposes the dedication into a mock popular song, recording loss rather than salvation.

Although conceived in ignorance of their ideas, Kahlo’s work appealed instantly to the Surrealists. For her 1938 exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York, Breton wrote a preface romantically linking Kahlo with Mexico’s prodigal natural beauty: ‘adorned like a fairy-tale princess, with magic spells at her fingertips, an apparition in the flash of light of the quetzal bird which scatters opals among the rocks as it flies away.’ Her paintings combine child-like directness with a sophisticated exploration of ‘the eye’s capacity to pass from visual power to visionary power’.

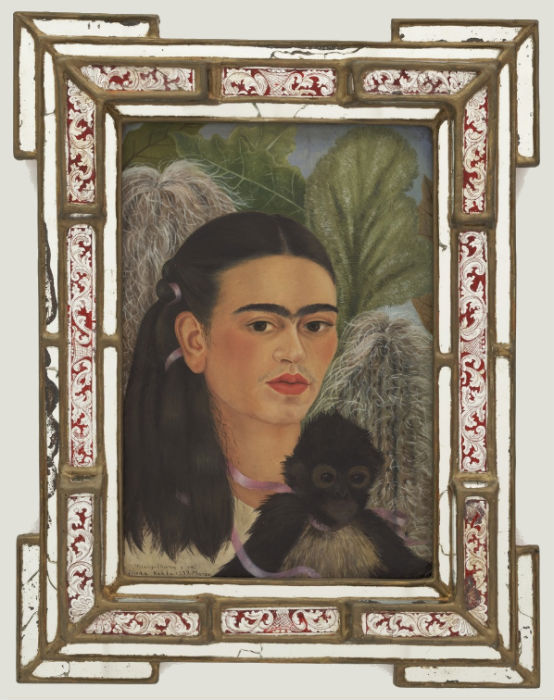

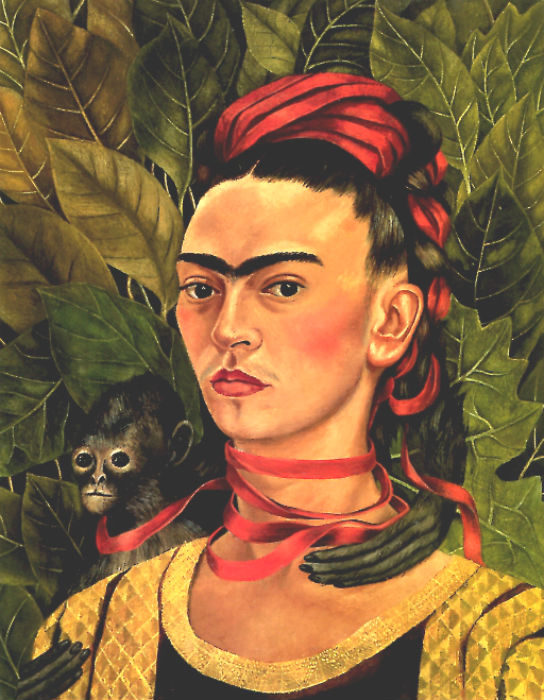

Frida Kahlo, Fulang-Chang and I, 1937/39

Kahlo’s self-portraits are as highly composed as her own elaborately adorned image. However, rather than depicting herself as artist-subject in the act of painting, her trope is the mirror; the painting itself becomes the mirror device, and sometimes she added a brightly coloured border like those of Mexican tin mirrors.

In Self-Portrait with Monkey she wears a blood-red ribbon that winds through her hair and round her neck. Hayden Herrera in Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo (1983) suggests that the ribbon links her ‘as a metaphoric blood-line’ to a pet spider monkey whose paws embrace her: pets increasingly took the place of the children she could not have. She scrutinises the two faces, one almost human, her own slightly masculine, with heavy black brows meeting like a bird’s wings, and faint moustache. Her own calm proud stare and the monkey’s dignity mask a sense of danger and wilderness.

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Monkey, 1940

The ribbon also echoes Breton’s comment in 1938: ‘There is no art more exclusively feminine, in the sense that, in order to be as seductive as possible, it is only too willing to play alternately at being absolutely pure and absolutely pernicious. The art of Frida Kahlo is a ribbon around a bomb.’

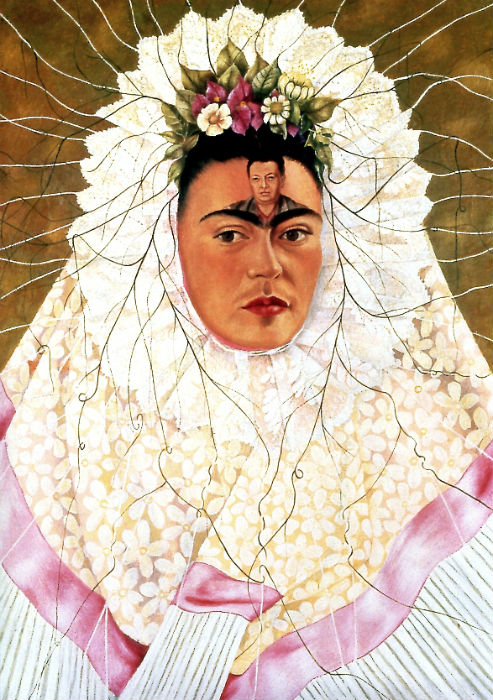

VERONIKA KAVASS ON ‘SELF-PORTRAIT AS A TEHUANA’

Kahlo started working on this self-portrait a few months after Rivera filed for a divorce in 1939. She is clothed in a Tehuana dress as an homage to Rivera’s admiration for traditional Mexican costumes. Rivera’s face appears as her third eye, a reference to her obsessive suffering surrounding his constant infidelity—she could not take him off her mind. Kahlo’s Tehuana gown expands into a spider web, one that Rivera is trapped inside of.

From Veronica Kavass, Artists in Love (New York: Rizzoli, 2012)

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait as a Tehuana, 1940/43