Gustave Courbet

The Origin of the World

Gustave Courbet, The Origin of the World, 1866

Gustave Courbet, Woman with White Stockings, c. 1846

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Five Chapter 6

When you surprised yourself in the mirror, when you became a stranger to yourself, who was the who you dreamt yourself to be?

̶ Mirror, mirror, tell no lies, how do I look in Courbet’s eyes?

̶ The arabesques of your shirt rise to reveal the fullness of your breast; the lustre of your belly throws into relief the intoxicating cleft: Unspeakable, overabounding, your demonic majesty sends a shudder down the observer’s spine: Trembling in blank wonder, he is blinded by the sun. And yet it is night that resides between your thighs, it is darkness that radiates this light. He is no longer master of his own eyes: It is you who strain toward him, it is you who compel his gaze.

̶ My demon twin, so intimate, so alien, your devastating presence takes my breath away. How you move me! There was a time when I disowned you, taking you for a foreign body. I couldn’t accept your black magic, I couldn’t bear how you shattered my self-image. In a frenzy of friction I tried to make you mine: the greater was my frustration. Then a day finally came when I could reclaim you, and on that day I bought a new dress: A dress to make whole the two halves of my body, a dress to integrate the top and the bottom. Alas, it was not the dress that would give a final certainty to my femininity! And so relentlessly I pursued the enigma of my desire, and so incessantly I renewed my second skin.

LINDA NOCHLIN ON THE NUDE IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN

From Linda Nochlin and Joëlle Bolloch, Women in the 19th Century: Categories and Contradictions (New York: The New Press, published in conjunction with the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, 1997).

Within official salon culture, it was the nude that was considered the pinnacle of artistic achievement, preeminently in the form of history painting, the traditional realm of classical or Biblical iconography. We tend to think of the nude today exclusively in terms of the female figure, but this was certainly not the case in earlier periods. For the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century (male) artist, the ultimate test of artistic ability lay in the realm of the male nude and the heroic subject. One of the tests that young would-be academicians had to face was the representation of the male nude from life: the so-called académie. The identification of the nude with the naked female specifically does not occur until the middle of the nineteenth century and is the result of many factors, including the gradual replacement of the official commission and the aristocratic patron with the art market and the private dealer as the center of artistic commerce, the invention of photography, and the simultaneous commodification and democratization of the consumption of visual imagery.

A consideration of the place of the nude in early photography is relevant to any discussion of the female nude in high art. One of the earliest uses to which the new visual medium was put was the creation of pornography, hard and soft: the naked woman in a variety of salacious poses and positions, with companions, male or female, or alone, created for the consumption of a new male market for visual erotica. Artists’ photographic series—nudes in various ‘classical’ and ‘romantic’ poses—were made available to painters at the same time. These series offered the added attraction of convenience and relative cheapness: the nude photograph was already two-dimensional and much cheaper than hiring a model. In both cases, that of pornography and the model series, photography was believed to provide ‘authentic’ visual information about the naked female body, an indexical truth that no mere painted image could supply.

Anonymous, Nude Woman, Arm on Head, daguerreotype, c. 1850

Works like Ingres’s La Source of 1856, in comparison to earlier female nudes by the same master—his Odalisque of 1814, for instance, or his very similar Venus Anadyomene (1808 and 1848), both far more linear, sinuous, planar, and abstract in their treatment of the body—reveal, however much Maître Ingres himself might deny it, the impact of the visual realism of photography on the aging master’s concept of feminine sensuality, in the softening and blurring of the contours, the inviting droop of the belly, the come-hither glance of the model, the vagueness of the reference to classical antiquity.

Ingres, La Source, 1856

Ingres, Odalisque with Female Slave, 1842

Ingres, Venus Anadyomene, 1825-50

All this points to a newer vision of feminine sensuality, far, it is true, from the beefy descriptive naturalism of the outrageous Courbet’s female Bather of three years earlier, which Emperor Napoleon III is said to have dubbed ‘a Percheron,’ likening the figure’s muscular buttocks to those of the animals in Rosa Bonheur’s Horse-Fair, which had appeared in the same Salon, but more naturalistic than the ‘classic’ Ingres of the past, nevertheless.

Gustave Courbet, The Bathers, 1853

Rosa Bonheur, The Horse Fair, 1853

It is in the context of works like this, or the even more highly polished, artificially posed, but adorably fleshy, heroine of Cabanel’s Naissance de Venus of 1863, that we must situate Manet’s Olympia (1863) and the shock waves it created in the Salon of 1865. ‘Female gorilla,’ ‘yellow-bellied Venus,’ ‘dirty flesh tones,’ ‘crude as an image d’Epinal’—these were some of the choicer epithets hurled at the ‘majestic young lady’ at the time of its first public appearance. Even Courbet, the radical of the previous generation, was taken aback by the nude’s emphatic physical and emotional flatness, calling the figure ‘a queen of spades from a deck of cards.’ Only Emile Zola, Manet’s prime defender at the time, really got the point. The young novelist and critic, who had scathingly denominated Cabanel’s popular Venus a ‘delicious lorette… made out of a sort of pink and white marzipan’ was perspicacious enough in his visual judgment to realize that with Olympia, as well as in his representation of the scandalously naked Victorine in Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe, Manet had indeed invented the nude of modern times: arrogant, challenging, formally anti-illusionistic, but psychologically realistic. Not Venus, but a body for sale on a bed: this was the authentic image of modern life, cast in the form of a woman’s unclothed body.

Edouard Manet, Olympia, 1863

Alexandre Cabanel, The Birth of Venus, 1863

Constantin Guys, Officers and Courtesans in an Interior, c. 1850

Indeed, the prostitutional body, clothed, semi-clothed, or seductively nude, could, in some ways, be said to stand for modernity itself, in the work of vanguard writers and visual artists of the Second Empire and Third Republic. The poet and critic Baudelaire, in his paean to the fashionable illustrator Constantin Guys, ‘The Painter of Modern Life,’ extolled his hero’s imagery of the brothel and the low dive, where tawdry whores, breasts bared, eyes rimmed with kohl, displayed their artificially assisted charms for the delectation of soldiers and sailors, and praised as well Guys’s elegant sketches of famous courtesans of the day, resplendent in the most exaggerated crinolines, shaded by ruffled parasols in their carriages at the Bois, either alone or accompanied by their equally elegant, top-hatted protectors. From the lowest to the highest, the public women personified the mores, the fashions, the very look of modernity. In the Baudelarian sense, therefore, they personified modern beauty itself: that aspect of the beautiful which was fleeting, evanescent, mobile—and exciting for that very reason, in a way that the old, timeless, stable, classical beauty never could be.

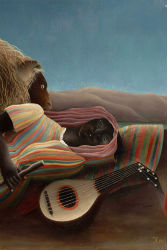

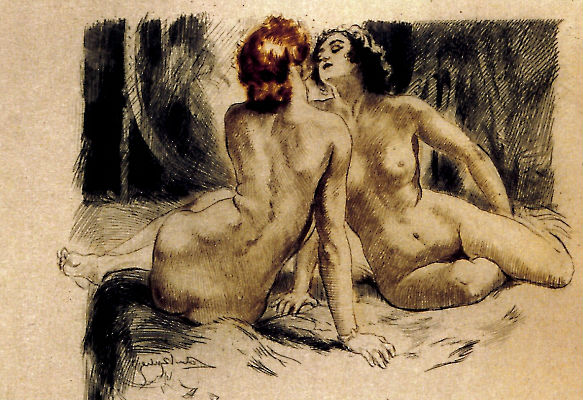

Famous artists, as well as photographers and illustrators, catered to the desiring gaze of wealthy patrons and their special needs. Courbet, for instance, was commissioned in 1866 by Khalil Bey, Turkish ambassador to the Court of St. Petersburg and Parisian man-about-town, to create the large scale image of two lesbians locked in a somnolent embrace. The two nudes now hang in the Petit Palais and are known as The Sleepers. One light and fair-skinned (the ingenue, in the conventional language of erotica), the other brunette and darker (the experienced half of the perverse couple, according to the same code), the two intertwined, lovingly detailed bodies are calculated to rouse the appetites of the most jaded roué, at the same time that they make reference to Baudelaire’s famous, doomed lesbian couple, Delphine and Hyppolyte, whose ecstasy and despair were recorded in ‘Femmes damnées.’

The full text of Baudelaire’s poem is given in Richard Howard’s excellent translation at the end of this essay.

Gustave Courbet, The Sleepers, 1866

Gustave Courbet, La belle irlandaise, 1865

The model is Joanna Hiffernan, who also modelled for The Sleepers and, it is thought, L’origine du monde.

Still more explicitly pornographic is the other work Courbet created on commission for the same collector, the so-called L’Origine du Monde, the realistically painted bas ventre of a woman writhing in sexual excitement, a belly ‘as beautiful as the flesh of a Correggio,’ in the words of Courbet’s contemporary, Edmond de Goncourt (Journal, June 1889). Another contemporary, Maxime du Camp, was less laudatory in his estimation of the work. ‘By some inconceivable forgetfulness, the artist, who copied his model from nature, had neglected to represent the feet, the legs, the thighs, the stomach, the hips, the chest, the hands, the arms, the shoulders, the neck and the head,’ he declared sarcastically in the pages of his four-volume denunciation of the Paris Commune in which Courbet had been an active participant. Formerly kept behind a discreet green curtain by its owner, who regaled selected male friends with a display of the L’Origine after dinner with the cigars, it was later veiled by a provocative, sexualized landscape panel painted for the purpose by the surrealist Masson when it graced the country house of the famous psychoanalytic theorist Jacques Lacan. Today L’Origine is openly displayed on the walls of the Musée d’Orsay, attaining the status of high art by virtue of this change of venue—and by virtue of an even more dramatic change in sexual mores!

The same might be said of Degas’s remarkable series of brothel monotypes, intimate and sometimes salacious views of prostitutes and their clients in their natural habitat, originally meant for private delectation, now available for public entertainment and instruction on the walls of museums, a staple of academic textbooks and slide lectures.

Edgar Degas, Three Women in a Brothel, Seen from Behind, c. 1877–79

Honoré Daumier, La République (nourrit ses enfants et les instruit), 1848

At the other end of the scale from the imagery of feminine abjection and debasement constituted by pornography or the brothel scene is the elevation accorded to the female figure through allegory. Here woman’s nudity stands not for her sexual availability but rather for the universality and timelessness of the message that nudity conveys. In a work like Daumier’s painted sketch of La République (created for a contest held under the Provisional government of the short-lived 1848 Revolution), for example, the powerful, exposed breasts of the semi-nude female stand not for sexual attraction but for the nurturing mission of the Republic vis-à-vis its citizens, her children. It is noteworthy that the ‘children’ seem to be male, the allegorical figure itself female: women, of course, did not receive the right to vote, to be full citizens of the French Republic, until after the Second World War. ‘Always an allegory, never a citizen,’ might be the refrain of French womanhood in the nineteenth century. Daumier, it might be noted, was an unrelenting foe of French women’s struggle for equality, pillorying professional women and female activists unmercifully in such 1840s caricature series as Les Divorceuses and Les Bas Bleus. The witty savagery of his attack on middle-class or ‘bohemian’ women who dared to demand the right to vote, to divorce, or lead creative professional lives should be compared with his sympathetic, even sentimental depiction of humble women who knew their places: laundresses burdened with bundles and baby, for example, or working-class mothers concerned only with nurturing their families. These prejudices, typical of the liberal or even radical men of the day, reached their acme in the views of the anarchist P.-J. Proudhon, who, in his La Pornocracie ou Les Femmes dans les Temps Modernes (left unfinished on the author’s death in 1865 and not published until ten years later), declared that woman must either fulfill her self-abnegating role of wife and mother or be considered a prostitute. These views were certainly shared by Daumier, who constructs his female allegorical figure on a maternal model.

Delacroix deploys a different construction for his dynamic and aggressive female activist, leading her male followers heroically over the barricade and the fallen bodies of the opposition, in his allegorical representation of his Liberty created for the Revolution of 1830.

Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People, 1830

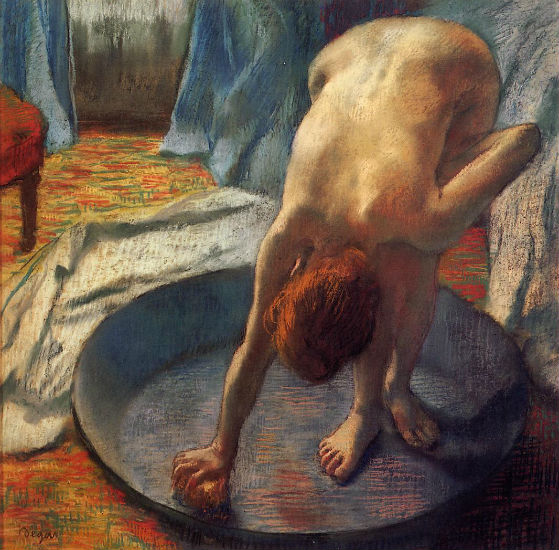

Edgar Degas, The Tub, 1886

Yet the female nude in the nineteenth century attained its apotheosis neither in pornography nor in allegory but in the more neutral genre of the bather. The period is marked by the gradual transformation of this time-honored theme from the narrative specificity and formal elevation of the classical Diana or the biblical Susannah to the baigneuse tout court. (The baigneur is a much rarer bird, confined to a few works by Bazille and Caillebotte, as well as a notable series, it is true, by Cézanne). It is in two series of bathers—indoors by Degas, and outdoors by Cézanne—that the nineteenth-century vanguard re-visioning of the female nude is achieved in all its fullness. Both of these artists approached their subjects in different ways: for Degas, it was the intimacy of the close-up glance, the awkwardness of the momentary pose of the woman absorbed in her toilette or getting in or out of the bathtub itself; the angle of vision that estranges and ‘makes new’ the familiar substance of the feminine body, focusing on a hunched shoulder, an elongated neck, an outstretched leg. The jewel-like, encrusted pastel surfaces of Degas’s late work inscribes the dimly adumbrated torsos of his models in a network of brilliant scratches and patches of tactile pigment, making the figures at once intensely present but physically unavailable to the viewer.

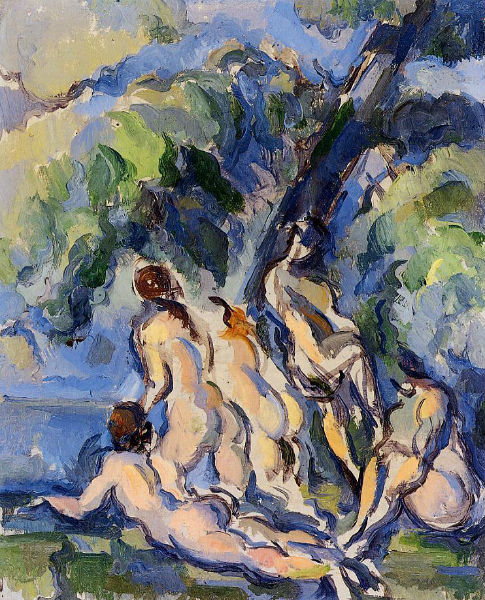

Cézanne’s strategies vis-à-vis the female bather were entirely different. For this artist, the nude was self-evidently a part of nature, enclosed by and articulated through a landscape setting. Cézanne’s figures increasingly depart from classical ideals of beauty or articulation, announcing themselves as pictorial creations rather than realistically depicted bodies. If the sexual energy and conflicted desire characteristic of the artist’s earlier approach to the naked female remain in the later versions, those of the 1890s and the first years of the twentieth century, they have been metamorphosed into formal intensity, a formal intensity nevertheless charged with the struggle to transform a sensory, and sensual, raw material (the stuff of memory and fantasy in the case of the female nudes, for Cézanne was not working from the too provocative model in these monumental paintings) into its pictorial equivalent: richly embodied, carefully judged strokes of pigment tensely deployed on the flat surface of the picture plane.

Paul Cézanne, Bathers, c. 1902-06

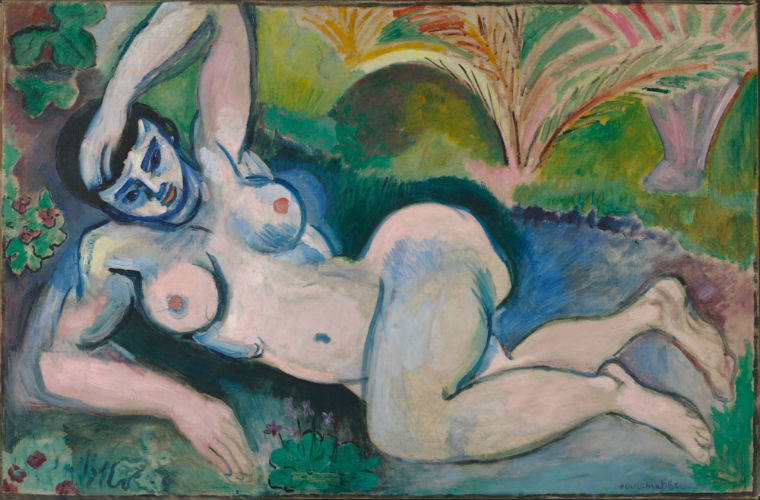

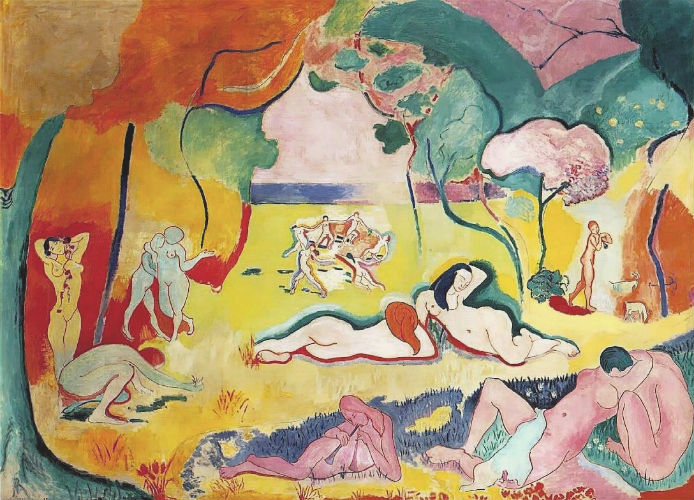

The impact of this struggle is still evident in the opening blast of the twentieth-century vanguard’s engagement with the female nude: Matisse’s Bonheur de vivre and his Blue Nude in the early years of this century, or, most overtly, in Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon, a work which at once returns to the brothel imagery of the nineteenth-century realists for its inspiration and sexual charge, but filters it through the formal innovations and anti-narrative iconography offered by Cézanne’s repertory of female nudes in his late bathers.

Henri Matisse, Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra), 1907

Henri Matisse, Le bonheur de vivre, 1906

BAUDELAIRE, ‘DAMNED WOMEN: DELPHINE AND HIPPOLYTA’

From Les fleurs du mal, translated by Richard Howard

Alméry Lobel-Riche, illustration for Les fleurs du mal, ‘Damned Women’, 1923

Disclosed, though dimly, by the faltering lamps,

Hippolyta rested on a soft and scented couch

reliving those caresses which had raised

the curtains of her inexperience.

Wild-eyed after the storm, she conjured up

already-distant skies of innocence,

just as a traveler might turn back to glimpse

blue horizons lost with the morning’s light.

The sluggish tears of her unfocussed gaze,

her eager arms flung down as in defeat —

every trace of voluptuous apathy

served and set off her fragile loveliness.

Reclining at her feet, elated yet calm,

Delphine stared up at her with shining eyes

the way a lioness wilt watch her prey

once her fangs have marked it for her own.

In all her pride the potent beauty knelt

before the pitiable one, complacently

savoring the wine of her triumph, reaching up

as though to garner fond acknowledgment.

She searched her victim’s eyes for evidence

of the silent canticle which pleasure sings

and that sublime and infinite gratitude

which glistens under the eyelids like a sigh.

‘Hippolyta, my angel, how do you feel now?

Surely you realize you must not grant

the holy sacrifice of your first bloom

to cruel gales that would disfigure it…

My kisses are as light as those May-flies

which graze the great transparent lakes at sunset;

his would trace their furrows on your flesh

like the tongue of some lacerating plow —

Alméry Lobel-Riche, illustration for Les fleurs du mal, ‘Damned Women’, 1923

Baudelaire, Les fleurs du mal, tr. Richard Howard

as if you had been trampled by a team

of oxen with inexorable hooves…

Hippolyta, sister! turn your face to me,

my heart and soul, my other half, my all!

Let me see your eyes, my heaven, my stars!

For one of their healing glances I shall trade

as yet untasted pleasures: you will drift

to sleep in my arms dreaming an endless dream!’

But then Hippolyta looked up: ‘Delphine,

I am grateful to you, I have no regrets,

yet I am troubled and my nerves are tense,

as if a dreadful feast had fouled the night…

Pangs of dread oppress me — I see ghosts

in black battalions beckoning me down

uncertain roads where each horizon ends

abruptly in a sky the color of blood.

What have we done – is it some wicked thing?

Must I endure this turmoil and this fear?

I cringe each time you call me ‘angel’, yet

I feel my mouth long for you. No, Delphine –

don’t look at me like that! I love you now

and I shalt love you always: I choose you,

even if my choice becomes a trap

laid for me, and the onset of my doom.’

With adamant eyes and a despotic voice,

Delphine replied, shaking her tragic mane

as if she stirred on the priestess’ tripod:

‘Who in love’s name dares to speak of Hell?

My curse forever on the dreaming fool

who entered first that endless labyrinth

and tried for all his folly to enlist

love in the service of morality!

Whoever hopes to force into accord

day and darkness, shadow and radiance,

will never warm his vacillating flesh

in that red sun our bodies know as love!

Go now – go find yourself some stupid boy

and give his lust your virgin heart to maul;

then, filled with horror, livid with disgust,

bring back to me your mutilated breasts…

Baudelaire, Les fleurs du mal

Le Procès des Fleurs du Mal

You cannot please two masters in this world!’

But then the girl, in a paroxysm of grief,

suddenly cried out: ‘There is emptiness

inside me – and that emptiness is my heart!

Searing as lava, deeper than the Void!

Nothing will satiate this monster’s greed,

nothing appease the Fury who puts out

her flaming torch within my very blood…

O draw the curtains – leave the world outside!

There must be rest for all this weariness.

Let me annihilate myself upon

your breast and find the solace of a grave!’

Downward, wretched victims! ever down

the path you follow: make your way to hell,

into the pit where crime arouses crime,

seething together in the thunder’s maw

and scourged by winds that never knew the sky

Down, frantic shades, and fall to your desires

where passion never slakes its raging thirst,

and from your pleasure stems your punishment.

Crack by crevice, into your sunless caves

feverish miasmas seep and gather strength

until they catch on fire like spirit-lamps,

imbuing your bodies with their vile perfume.

The harsh sterility of your delight

scalds your throat and desiccates your skin –

and the eyeless cyclone of concupiscence

rattles your flesh like an abandoned flag.

Wandering far from all mankind, condemned

to forage in the wilderness like wolves,

pursue your fate, chaotic souls, and flee

the infinite you bear within yourselves!

Manet, Baudelaire’s Mistress, Reclining, c. 1862

Nochlin & Bolloch, Women in the 19th Century

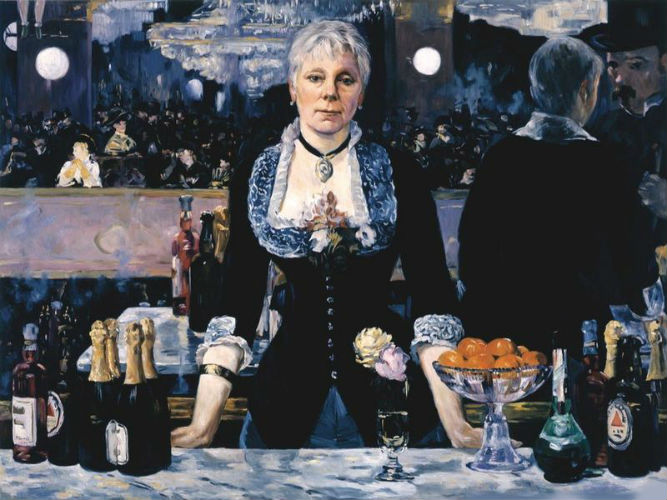

Kathleen Gilje, Linda Nochlin in Manet’s Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 2006

Musée d’Orsay, Paris